Next: Gravity Waves in Deep

Up: Waves in Incompressible Fluids

Previous: Introduction

Consider a stationary body of water, of uniform depth  , located on the surface of the Earth. This body is assumed to be sufficiently small compared to the Earth that its unperturbed surface is approximately planar. Let the Cartesian coordinate

, located on the surface of the Earth. This body is assumed to be sufficiently small compared to the Earth that its unperturbed surface is approximately planar. Let the Cartesian coordinate  measure vertical height, with

measure vertical height, with  corresponding to the aforementioned surface. Suppose that a small amplitude wave propagates horizontally through the water, and

let

corresponding to the aforementioned surface. Suppose that a small amplitude wave propagates horizontally through the water, and

let

be the associated velocity field.

be the associated velocity field.

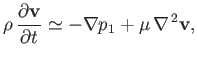

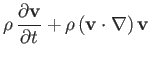

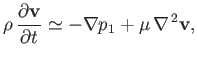

Because water is essentially incompressible, its equations of motion are

where  is the (uniform) mass density,

is the (uniform) mass density,  the (uniform) viscosity, and

the (uniform) viscosity, and  the (uniform) acceleration due to gravity.

(See Section 1.14.)

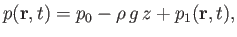

Let us write

the (uniform) acceleration due to gravity.

(See Section 1.14.)

Let us write

|

(11.3) |

where  is atmospheric pressure, and

is atmospheric pressure, and  the pressure perturbation due to the wave. Of course, in the absence of

the wave, the water pressure a depth

the pressure perturbation due to the wave. Of course, in the absence of

the wave, the water pressure a depth  below the surface is

below the surface is

. (See Chapter 2.)

Substitution into Equation (11.2) yields

. (See Chapter 2.)

Substitution into Equation (11.2) yields

|

(11.4) |

where we have neglected terms that are second order in small quantities (i.e., terms of order  ).

).

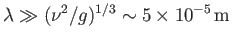

Let us also neglect viscosity, which is a good approximation provided that the wavelength is not ridiculously small. [For instance,

for gravity waves in water, viscosity is negligible as long as

.]

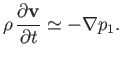

It follows that

.]

It follows that

|

(11.5) |

Taking the curl of this equation, we obtain

|

(11.6) |

where

is the vorticity. We conclude that the velocity field associated with the wave is irrotational. Consequently, the

previous equation is automatically satisfied by writing

is the vorticity. We conclude that the velocity field associated with the wave is irrotational. Consequently, the

previous equation is automatically satisfied by writing

|

(11.7) |

where

is the velocity potential. (See Section 4.15.) However, from Equation (11.1), the

velocity field is also divergence free. It follows that the velocity potential satisfies Laplace's equation,

is the velocity potential. (See Section 4.15.) However, from Equation (11.1), the

velocity field is also divergence free. It follows that the velocity potential satisfies Laplace's equation,

|

(11.8) |

Finally, Equations (11.5) and (11.7) yield

|

(11.9) |

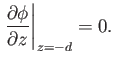

We now need to derive the physical

constraints that must be satisfied at

the water's upper and lower boundaries. It is assumed that the water is bounded from below by a

solid surface located at  . Because the water must always remain in contact

with this surface, the appropriate physical constraint at the lower boundary is

. Because the water must always remain in contact

with this surface, the appropriate physical constraint at the lower boundary is

(i.e., the normal velocity is zero

at the lower boundary), or

(i.e., the normal velocity is zero

at the lower boundary), or

|

(11.10) |

The water's upper boundary is a little more complicated, because it is a free surface.

Let  represent the vertical displacement of this surface due to the wave. It

follows that

represent the vertical displacement of this surface due to the wave. It

follows that

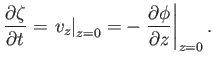

|

(11.11) |

The appropriate physical constraint at the upper boundary is that the water pressure there must equal atmospheric

pressure, because there cannot be a pressure discontinuity across a free surface (in the absence of surface tension--see Section 11.11).

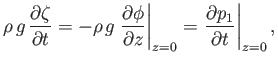

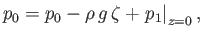

Accordingly, from Equation (11.3), we obtain

|

(11.12) |

or

|

(11.13) |

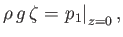

which implies that

|

(11.14) |

where use has been made of Equation (11.11).

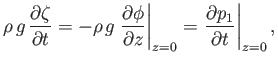

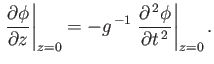

The previous expression can be combined with Equation (11.9) to give the boundary condition

|

(11.15) |

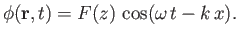

Let us search for a wave-like solution of Equation (11.8) of the form

|

(11.16) |

This solution actually corresponds to a propagating plane wave of wave vector

, angular frequency

, angular frequency  , and amplitude

, and amplitude  (Fitzpatrick 2013).

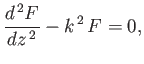

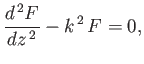

Substitution into Equation (11.8) yields

(Fitzpatrick 2013).

Substitution into Equation (11.8) yields

|

(11.17) |

whose independent solutions are

and

and

.

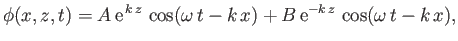

Hence, a general solution to Equation (11.8) takes the form

.

Hence, a general solution to Equation (11.8) takes the form

|

(11.18) |

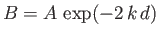

where  and

and  are arbitrary constants. The boundary condition (11.10)

is satisfied provided that

are arbitrary constants. The boundary condition (11.10)

is satisfied provided that

, giving

, giving

![$\displaystyle \phi(x,z,t) = A\left[{\rm e}^{\,k\,z}\ + {\rm e}^{-k\,(z+2\,d)}\right]\cos(\omega\,t-k\,x),$](img3921.png) |

(11.19) |

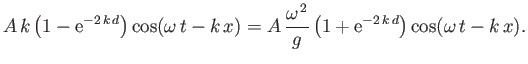

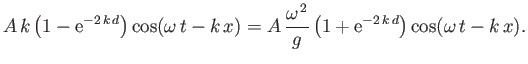

The boundary condition (11.15) then yields

|

(11.20) |

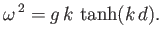

which reduces to the dispersion relation

|

(11.21) |

The type of wave described in this section is known as a gravity wave.

Next: Gravity Waves in Deep

Up: Waves in Incompressible Fluids

Previous: Introduction

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-03-31

![]() .]

It follows that

.]

It follows that

![]() . Because the water must always remain in contact

with this surface, the appropriate physical constraint at the lower boundary is

. Because the water must always remain in contact

with this surface, the appropriate physical constraint at the lower boundary is

![]() (i.e., the normal velocity is zero

at the lower boundary), or

(i.e., the normal velocity is zero

at the lower boundary), or