Next: Stokes Flow

Up: Incompressible Viscous Flow

Previous: Flow in Slowly-Varying Channels

It is well known that two solid bodies can slide over one another particularly easily when there is a thin layer of fluid sandwiched between them. Moreover, under certain

circumstances, a large positive pressure develops within the layer. This phenomenon is exploited in hydraulic bearings, whose aim is to substitute fluid-solid friction for the much larger friction that acts between solid bodies that are in direct contact with one another. Once set up,

the fluid layer in hydraulic bearings offers great resistance to being squeezed out, and is often capable of supporting a useful load.

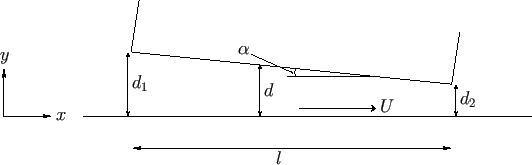

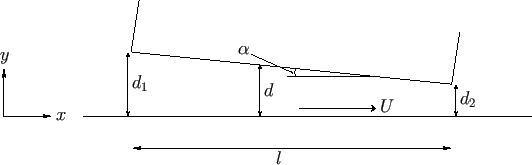

Figure 10.3:

The lubrication layer between two planes in relative motion.

|

Consider the simple two-dimensional case of a solid body with a plane surface (that is almost parallel to the  -

- plane) gliding steadily over another such body, the surface of the

gliding body being of finite length

plane) gliding steadily over another such body, the surface of the

gliding body being of finite length  in the direction of the motion (the

in the direction of the motion (the  -direction), and of infinite width (in the

-direction), and of infinite width (in the  -direction). (See Figure 10.3.) Experience shows that the plane surfaces

need to be slightly inclined to one another. Suppose that

-direction). (See Figure 10.3.) Experience shows that the plane surfaces

need to be slightly inclined to one another. Suppose that

is the angle of inclination. Let us transform to a

frame of reference in which the upper body is stationary. In this frame, the lower body moves in the

is the angle of inclination. Let us transform to a

frame of reference in which the upper body is stationary. In this frame, the lower body moves in the  -direction

at some fixed speed

-direction

at some fixed speed  . Suppose that the upper body extends from

. Suppose that the upper body extends from  to

to  , and that the

surface of the lower body corresponds to

, and that the

surface of the lower body corresponds to  . Let

. Let  be

the thickness (in the

be

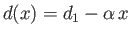

the thickness (in the  -direction) of the fluid layer trapped between the bodies, where

-direction) of the fluid layer trapped between the bodies, where  and

and  . It follows that

. It follows that

|

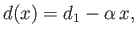

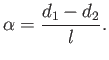

(10.63) |

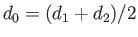

where

|

(10.64) |

As discussed in the previous

section, provided that

the cross-section of the channel between the two bodies is sufficiently slowly varying in the  -direction that the channel can be treated as effectively uniform at each point along its length. Thus, it follows from Equation (10.10) that the velocity profile within the channel takes the form

-direction that the channel can be treated as effectively uniform at each point along its length. Thus, it follows from Equation (10.10) that the velocity profile within the channel takes the form

![$\displaystyle v_x(x,y) = \frac{G(x)}{2\,\mu}\,y\left[d(x)-y\right]+ U\left[\frac{d(x)-y}{d}\right],$](img3696.png) |

(10.67) |

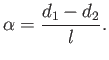

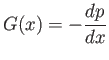

where

|

(10.68) |

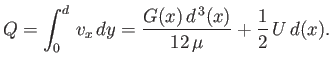

is the pressure gradient. Here, we are neglecting gravitational forces with respect to both pressure and viscous forces. The volume flux per unit width

(in the  -direction) of fluid along the channel is thus

-direction) of fluid along the channel is thus

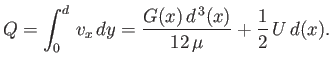

|

(10.69) |

Of course, in a steady state, this flux must be independent of  . Hence,

. Hence,

![$\displaystyle \frac{dp}{dx} = -G(x) = 6\,\mu\left[\frac{U}{d^{\,2}(x)}- \frac{2\,Q}{d^{\,3}(x)}\right],$](img3699.png) |

(10.70) |

where

. Integration of the previous equation yields

. Integration of the previous equation yields

![$\displaystyle p(x)-p_0 = \frac{6\,\mu}{\alpha}\left[U\left(\frac{1}{d}-\frac{1}{d_1}\right)-Q\left(\frac{1}{d^{\,2}}-\frac{1}{d_1^{\,2}}\right)\right],$](img3701.png) |

(10.71) |

where  . Assuming that the sliding block is completely immersed in fluid of uniform ambient pressure

. Assuming that the sliding block is completely immersed in fluid of uniform ambient pressure  , we would expect the

pressures at the two ends of the lubricating layer to both equal

, we would expect the

pressures at the two ends of the lubricating layer to both equal  , which implies that

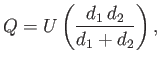

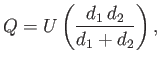

, which implies that  . It follows from the previous equation

that

. It follows from the previous equation

that

|

(10.72) |

and

![$\displaystyle p(x)-p_0 = \frac{6\,\mu\,U}{\alpha} \,\frac{[d_1-d(x)]\,[d(x)-d_2]}{d^{\,2}(x)\,(d_1+d_2)}.$](img3705.png) |

(10.73) |

Note that if  then the pressure increment

then the pressure increment  is positive throughout the layer, and vice versa. In other words, a

lubricating layer sandwiched between two solid bodies in relative motion only generates a positive pressure, that is capable of supporting a normal load, when the motion is such as to drag (by means of viscous stresses) fluid from the wider to the

narrower end of the layer. The pressure increment has a single maximum in the layer, and its value

at this point is of order

is positive throughout the layer, and vice versa. In other words, a

lubricating layer sandwiched between two solid bodies in relative motion only generates a positive pressure, that is capable of supporting a normal load, when the motion is such as to drag (by means of viscous stresses) fluid from the wider to the

narrower end of the layer. The pressure increment has a single maximum in the layer, and its value

at this point is of order

, assuming that

, assuming that

is of order unity. This suggests that

very large pressures can be set up inside a thin lubricating layer.

is of order unity. This suggests that

very large pressures can be set up inside a thin lubricating layer.

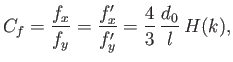

The net normal force (per unit width in the  -direction) acting on the lower plane is

-direction) acting on the lower plane is

![$\displaystyle f_y = -\int_0^l[p(x)-p_1]\,dx = -\frac{6\,\mu\,U}{\alpha^{\,2}}\left[\ln\left(\frac{d_1}{d_2}\right)-2\left(\frac{d_1-d_2}{d_1+d_2}\right)\right].$](img3710.png) |

(10.74) |

Moreover, the net tangential force (per unit width) acting on the lower plane is

![$\displaystyle f_x = \int_0^l\mu\left(\frac{\partial v_x}{\partial y}\right)_{y=...

...[2\ln\left(\frac{d_1}{d_2}\right)-3\left(\frac{d_1-d_2}{d_1+d_2}\right)\right].$](img3711.png) |

(10.75) |

Of course, equal and opposite forces,

act on the upper plane. Here,

is the mean channel width, and

is the mean channel width, and

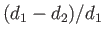

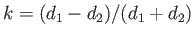

. It can be seen that if

. It can be seen that if  then

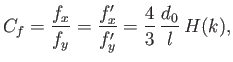

then  . The effective coefficient of friction,

. The effective coefficient of friction,  , between the two sliding bodies is conventionally defined as the ratio of the tangential to the normal force that

they exert on one another. Hence,

, between the two sliding bodies is conventionally defined as the ratio of the tangential to the normal force that

they exert on one another. Hence,

|

(10.78) |

where

![$\displaystyle H(k) = k\left.\left[\ln\left(\frac{1+k}{1-k}\right)-\frac{3\,k}{2}\right]\right/\left[\ln\left(\frac{1+k}{1-k}\right)-2\,k\right].$](img3721.png) |

(10.79) |

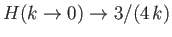

The function  is a monotonically decreasing function of

is a monotonically decreasing function of  in the range

in the range  . In fact,

. In fact,

, whereas

, whereas

. Thus, if

. Thus, if

[i.e., if

[i.e., if

] then

] then

. In other words, the effective coefficient of friction between two solid bodies in relative motion that

are separated by a thin fluid layer is independent of the fluid viscosity, and much less than unity. This result is significant because the coefficient of friction between two solid bodies in relative

motion that are in direct contact with one another is typical of order unity. Hence, the presence of a thin lubricating layer does indeed lead to a

large reduction in the frictional drag acting between the bodies.

. In other words, the effective coefficient of friction between two solid bodies in relative motion that

are separated by a thin fluid layer is independent of the fluid viscosity, and much less than unity. This result is significant because the coefficient of friction between two solid bodies in relative

motion that are in direct contact with one another is typical of order unity. Hence, the presence of a thin lubricating layer does indeed lead to a

large reduction in the frictional drag acting between the bodies.

Next: Stokes Flow

Up: Incompressible Viscous Flow

Previous: Flow in Slowly-Varying Channels

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-03-31

![]() -

-![]() plane) gliding steadily over another such body, the surface of the

gliding body being of finite length

plane) gliding steadily over another such body, the surface of the

gliding body being of finite length ![]() in the direction of the motion (the

in the direction of the motion (the ![]() -direction), and of infinite width (in the

-direction), and of infinite width (in the ![]() -direction). (See Figure 10.3.) Experience shows that the plane surfaces

need to be slightly inclined to one another. Suppose that

-direction). (See Figure 10.3.) Experience shows that the plane surfaces

need to be slightly inclined to one another. Suppose that

![]() is the angle of inclination. Let us transform to a

frame of reference in which the upper body is stationary. In this frame, the lower body moves in the

is the angle of inclination. Let us transform to a

frame of reference in which the upper body is stationary. In this frame, the lower body moves in the ![]() -direction

at some fixed speed

-direction

at some fixed speed ![]() . Suppose that the upper body extends from

. Suppose that the upper body extends from ![]() to

to ![]() , and that the

surface of the lower body corresponds to

, and that the

surface of the lower body corresponds to ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be

the thickness (in the

be

the thickness (in the ![]() -direction) of the fluid layer trapped between the bodies, where

-direction) of the fluid layer trapped between the bodies, where ![]() and

and ![]() . It follows that

. It follows that

![$\displaystyle v_x(x,y) = \frac{G(x)}{2\,\mu}\,y\left[d(x)-y\right]+ U\left[\frac{d(x)-y}{d}\right],$](img3696.png)

![$\displaystyle \frac{dp}{dx} = -G(x) = 6\,\mu\left[\frac{U}{d^{\,2}(x)}- \frac{2\,Q}{d^{\,3}(x)}\right],$](img3699.png)

![$\displaystyle p(x)-p_0 = \frac{6\,\mu}{\alpha}\left[U\left(\frac{1}{d}-\frac{1}{d_1}\right)-Q\left(\frac{1}{d^{\,2}}-\frac{1}{d_1^{\,2}}\right)\right],$](img3701.png)

![$\displaystyle p(x)-p_0 = \frac{6\,\mu\,U}{\alpha} \,\frac{[d_1-d(x)]\,[d(x)-d_2]}{d^{\,2}(x)\,(d_1+d_2)}.$](img3705.png)

![]() -direction) acting on the lower plane is

-direction) acting on the lower plane is

![$\displaystyle f_y = -\int_0^l[p(x)-p_1]\,dx = -\frac{6\,\mu\,U}{\alpha^{\,2}}\left[\ln\left(\frac{d_1}{d_2}\right)-2\left(\frac{d_1-d_2}{d_1+d_2}\right)\right].$](img3710.png)

![$\displaystyle f_x = \int_0^l\mu\left(\frac{\partial v_x}{\partial y}\right)_{y=...

...[2\ln\left(\frac{d_1}{d_2}\right)-3\left(\frac{d_1-d_2}{d_1+d_2}\right)\right].$](img3711.png)

![$\displaystyle = -f_x = \frac{\mu\,U\,l^{\,2}}{d_0^{\,2}}\,\frac{3}{2\,k^2}\left[\ln\left(\frac{1+k}{1-k}\right)-2\,k\right],$](img3713.png)

![$\displaystyle =-f_y = \frac{\mu\,U\,l}{d_0}\,\frac{1}{k}\left[2\ln\left(\frac{1+k}{1-k}\right)-3\,k\right],$](img3715.png)

![$\displaystyle H(k) = k\left.\left[\ln\left(\frac{1+k}{1-k}\right)-\frac{3\,k}{2}\right]\right/\left[\ln\left(\frac{1+k}{1-k}\right)-2\,k\right].$](img3721.png)