Multi-Slit Interference

Suppose that the interference apparatus pictured in Figure 10.1 is modified such that  identical slits of width

identical slits of width

,

running parallel to the

,

running parallel to the  -axis, are cut in the

opaque screen that occupies the plane

-axis, are cut in the

opaque screen that occupies the plane  . Let the slits be located at

. Let the slits be located at  , for

, for  . For the sake of

simplicity, the arrangement of slits is assumed to

be symmetric with respect to the plane

. For the sake of

simplicity, the arrangement of slits is assumed to

be symmetric with respect to the plane  . In other words, if there is a slit at

. In other words, if there is a slit at  then there is also

a slit at

then there is also

a slit at  .

The distance between the

.

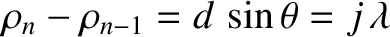

The distance between the  th slit and a

point on the projection screen that is an angular distance

th slit and a

point on the projection screen that is an angular distance  from the plane

from the plane  is [cf., Equation (10.3)]

is [cf., Equation (10.3)]

![$\displaystyle \rho_n = R\left[1-\frac{x_n}{R}\,\sin\theta + {\cal O}\left(\frac{x_n^{\,2}}{R^{\,2}}\right)\right].$](img3369.png) |

(10.31) |

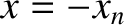

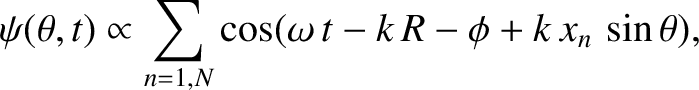

Thus, making use of the far-field

orderings (10.10), where  now represents the typical spacing between neighboring slits,

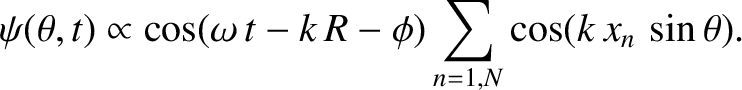

and assuming normally incident collimated light, Equation (10.5) generalizes to

now represents the typical spacing between neighboring slits,

and assuming normally incident collimated light, Equation (10.5) generalizes to

|

(10.32) |

which can also be written

|

(10.33) |

|

(10.34) |

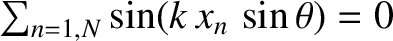

Here, we have made use of the fact that arrangement of slits is symmetric with respect to the plane

[which implies that

[which implies that

]. We have also employed the trigonometrical

identity

]. We have also employed the trigonometrical

identity

. (See Appendix B.)

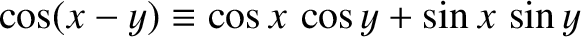

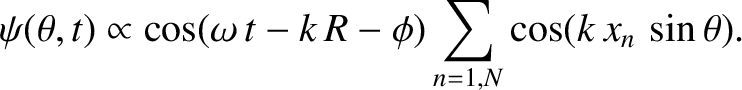

It follows that the intensity of

the interference pattern appearing on the projection screen is specified by

. (See Appendix B.)

It follows that the intensity of

the interference pattern appearing on the projection screen is specified by

![$\displaystyle {\cal I}(\theta) \propto \langle \psi^{\,2}(\theta,t)\rangle \pro...

...um_{n=1,N} \cos\left(2\pi\,\frac{x_n}{\lambda}\,\sin\theta\right)\right]^{\,2},$](img3374.png) |

(10.35) |

because

.

The previous expression is a generalization of Equation (10.12).

.

The previous expression is a generalization of Equation (10.12).

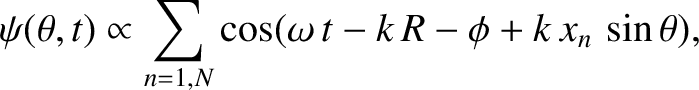

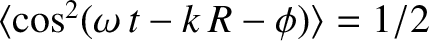

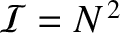

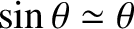

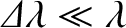

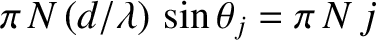

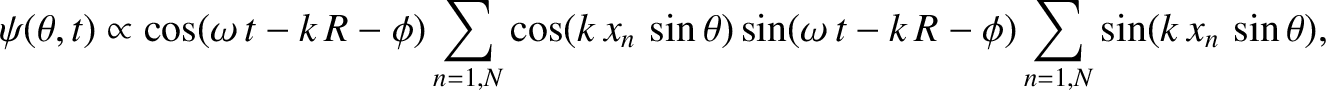

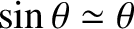

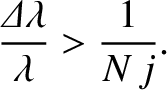

Figure 10.8:

Multi-slit far-field interference pattern calculated for  and

and

with normal

incidence and narrow slits.

with normal

incidence and narrow slits.

|

|

Suppose that the slits are evenly spaced a distance  apart, so that

apart, so that

![$\displaystyle x_n = [n-(N+1)/2]\,d$](img3376.png) |

(10.36) |

for  . It follows that

. It follows that

![$\displaystyle {\cal I}(\theta) \propto \left[\sum_{n=1,N} \cos\left(2\pi\,[n-(N+1)/2]\,\frac{d}{\lambda}\,\sin\theta\right)\right]^{\,2},$](img3377.png) |

(10.37) |

which can be summed to give

![$\displaystyle {\cal I}(\theta)\propto \frac{\sin^2[\pi\,N\,(d/\lambda)\,\sin\theta]}{\sin^2[\pi\,(d/\lambda)\,\sin\theta)]}.$](img3378.png) |

(10.38) |

(See Exercise 1.)

The multi-slit interference function, (10.38), exhibits strong maxima in situations in which

its numerator and denominator are simultaneously zero; that is, when

|

(10.39) |

where

is an integer. In this situation, application of l'Hopital's rule yields

is an integer. In this situation, application of l'Hopital's rule yields

. The

heights of these so-called principal maxima in the interference function are very large, being proportional to

. The

heights of these so-called principal maxima in the interference function are very large, being proportional to  , because

there is constructive

interference of the light from all

, because

there is constructive

interference of the light from all  slits. This occurs because the distances between neighboring

slits and the point on the projection screen at which a given maximum is located differ by an integer number of wavelengths; that is,

slits. This occurs because the distances between neighboring

slits and the point on the projection screen at which a given maximum is located differ by an integer number of wavelengths; that is,

. All of the principal maxima have the same height.

. All of the principal maxima have the same height.

The multi-slit interference function (10.38) is zero when

its numerator is zero, but its denominator non-zero; that is, when

|

(10.40) |

where

is an integer that is not an integer multiple of

is an integer that is not an integer multiple of  . It follows that there are

. It follows that there are  zeros between neighboring

principal maxima. It can also be demonstrated that there are

zeros between neighboring

principal maxima. It can also be demonstrated that there are  secondary maxima between

neighboring principal maxima. However, these maxima are much lower in height, by a factor of order

secondary maxima between

neighboring principal maxima. However, these maxima are much lower in height, by a factor of order  , than the primary maxima.

, than the primary maxima.

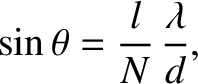

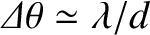

Figure 10.8 shows the typical far-field interference pattern produced by a system of ten identical,

equally spaced, parallel slits, assuming normal incidence and narrow slits, when the slit spacing,  , greatly exceeds the wavelength,

, greatly exceeds the wavelength,  ,

of the light (which, as we saw in Section 10.2, is the most interesting case). It can be seen that the

pattern consists of a series of bright fringes of equal intensity, separated by much wider

(relatively) dark fringes. The bright fringes correspond to the principal maxima discussed previously. As is the case for two-slit interference, the innermost (i.e., low

,

of the light (which, as we saw in Section 10.2, is the most interesting case). It can be seen that the

pattern consists of a series of bright fringes of equal intensity, separated by much wider

(relatively) dark fringes. The bright fringes correspond to the principal maxima discussed previously. As is the case for two-slit interference, the innermost (i.e., low  , small

, small  ) principal maxima are approximately equally spaced, with a characteristic angular

spacing

) principal maxima are approximately equally spaced, with a characteristic angular

spacing

. [This

result follows from Equation (10.39), and the small-angle approximation

. [This

result follows from Equation (10.39), and the small-angle approximation

.] However, the typical angular width of a principal maximum

(i.e., the angular distance between the maximum and the closest zeroes on either side of it) is

.] However, the typical angular width of a principal maximum

(i.e., the angular distance between the maximum and the closest zeroes on either side of it) is

. [This result follows from Equation (10.40), and the small-angle approximation.] The ratio of the angular width of a principal maximum to the angular spacing between successive maxima is thus

. [This result follows from Equation (10.40), and the small-angle approximation.] The ratio of the angular width of a principal maximum to the angular spacing between successive maxima is thus

|

(10.41) |

Hence, we conclude that, as the number of slits increases, the bright fringes in a multi-slit interference pattern become progressively sharper.

The most common practical application of multi-slit interference is the transmission diffraction grating. Such a device consists

of  identical, equally spaced, parallel scratches on one side of a thin uniform transparent glass, or plastic, film. When the film is illuminated, the scratches

strongly scatter the incident light, and effectively constitute

identical, equally spaced, parallel scratches on one side of a thin uniform transparent glass, or plastic, film. When the film is illuminated, the scratches

strongly scatter the incident light, and effectively constitute  identical, equally spaced, parallel line sources. Hence, the grating generates

the type of

identical, equally spaced, parallel line sources. Hence, the grating generates

the type of  -slit interference pattern discussed previously, with one major difference. Namely, the central (

-slit interference pattern discussed previously, with one major difference. Namely, the central ( ) principal maximum has

contributions not only from the scratches, but also from all the transparent material between the scratches. Thus, the central

principal maximum is considerably brighter than the other (

) principal maximum has

contributions not only from the scratches, but also from all the transparent material between the scratches. Thus, the central

principal maximum is considerably brighter than the other ( ) principal maxima.

) principal maxima.

Diffraction gratings are often employed in spectroscopes, which are instruments used to decompose light that is

made up of a mixture of different wavelengths into its

constituent wavelengths. As a simple example, suppose that a spectroscope contains an  -line diffraction grating that is illuminated, at normal incidence,

by a mixture of light of wavelength

-line diffraction grating that is illuminated, at normal incidence,

by a mixture of light of wavelength  , and light of wavelength

, and light of wavelength

, where

, where

. As always, the overall interference pattern (i.e., the overall wavefunction at the projection screen) produced by the grating is a linear superposition

of the pattern generated by the light of wavelength

. As always, the overall interference pattern (i.e., the overall wavefunction at the projection screen) produced by the grating is a linear superposition

of the pattern generated by the light of wavelength  , and the pattern generated by the

light of wavelength

, and the pattern generated by the

light of wavelength

. Consider the

. Consider the  th-order principal maximum associated

with the wavelength

th-order principal maximum associated

with the wavelength  interference pattern, which is located at

interference pattern, which is located at  , where

, where

. [See Equation (10.39).] Here,

. [See Equation (10.39).] Here,  is

the spacing between neighboring lines on the diffraction grating, which is assumed to be greater than

is

the spacing between neighboring lines on the diffraction grating, which is assumed to be greater than  . (Incidentally, the

width of the lines is assumed to be much less than

. (Incidentally, the

width of the lines is assumed to be much less than  .)

The maximum in question has a finite angular width.

We can determine this width by locating the zeros in the interference pattern on either side of the maximum. Let the zeros

be

located at

.)

The maximum in question has a finite angular width.

We can determine this width by locating the zeros in the interference pattern on either side of the maximum. Let the zeros

be

located at

.

The maximum itself corresponds to

.

The maximum itself corresponds to

. Hence, the

zeros correspond to

. Hence, the

zeros correspond to

(i.e.,

they correspond to the first zeros of the function

(i.e.,

they correspond to the first zeros of the function

![$\sin[\pi\,N\,(d/\lambda)\,\sin\theta]$](img3396.png) on either side of the zero at

on either side of the zero at  .) [See Equation (10.38).]

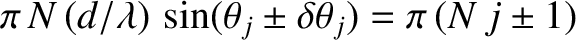

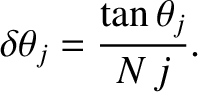

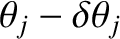

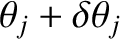

Taylor expanding to first order in

.) [See Equation (10.38).]

Taylor expanding to first order in

, we obtain

, we obtain

|

(10.42) |

Hence, the maximum in question effectively extends from

to

to

.

Consider the

.

Consider the  th-order principal maximum associated with the wavelength

th-order principal maximum associated with the wavelength

interference pattern, which is

located at

interference pattern, which is

located at

, where

, where

. [See Equation (10.39).] Taylor

expanding to first order in

. [See Equation (10.39).] Taylor

expanding to first order in

, we obtain

, we obtain

|

(10.43) |

In order for the spectroscope to resolve the incident light into its two constituent wavelengths, at the  th spectral order, the angular spacing,

th spectral order, the angular spacing,

, between the

, between the

th-order maxima associated with these two wavelengths must be greater than the angular widths,

th-order maxima associated with these two wavelengths must be greater than the angular widths,

, of the

maxima themselves. If this is the case then the overall

, of the

maxima themselves. If this is the case then the overall  th-order maximum will consist of two closely spaced maxima, or “spectral lines” (centered at

th-order maximum will consist of two closely spaced maxima, or “spectral lines” (centered at  and

and

). On the other hand, if this is not the case then the two maxima will merge to form a single maximum, and it will

consequently not be possible to tell that the incident light consists of a mixture of two different wavelengths. Thus, the condition

for the spectroscope to be able to resolve the spectral lines at the

). On the other hand, if this is not the case then the two maxima will merge to form a single maximum, and it will

consequently not be possible to tell that the incident light consists of a mixture of two different wavelengths. Thus, the condition

for the spectroscope to be able to resolve the spectral lines at the  th spectral order is

th spectral order is

, or

, or

|

(10.44) |

We conclude that the resolving power of a diffraction grating spectroscope increases as the number of illuminated lines

(i.e.,  ) increases, and also as the spectral order (i.e.,

) increases, and also as the spectral order (i.e.,  ) increases. Incidentally, there

is no resolving power at the lowest (i.e.,

) increases. Incidentally, there

is no resolving power at the lowest (i.e.,  ) spectral order, because the corresponding principal maximum is located at

) spectral order, because the corresponding principal maximum is located at  irrespective of the wavelength of the incident light. Moreover, there is a limit to how large

irrespective of the wavelength of the incident light. Moreover, there is a limit to how large  can become (i.e., a given diffraction

grating, illuminated by light of a given wavelength, has a finite number of principal maxima). This follows because

can become (i.e., a given diffraction

grating, illuminated by light of a given wavelength, has a finite number of principal maxima). This follows because

cannot

exceed unity, so, according to Equation (10.39),

cannot

exceed unity, so, according to Equation (10.39),  cannot exceed

cannot exceed  .

.

identical slits of width

identical slits of width

,

running parallel to the

,

running parallel to the  -axis, are cut in the

opaque screen that occupies the plane

-axis, are cut in the

opaque screen that occupies the plane  . Let the slits be located at

. Let the slits be located at  , for

, for  . For the sake of

simplicity, the arrangement of slits is assumed to

be symmetric with respect to the plane

. For the sake of

simplicity, the arrangement of slits is assumed to

be symmetric with respect to the plane  . In other words, if there is a slit at

. In other words, if there is a slit at  then there is also

a slit at

then there is also

a slit at  .

The distance between the

.

The distance between the  th slit and a

point on the projection screen that is an angular distance

th slit and a

point on the projection screen that is an angular distance  from the plane

from the plane  is [cf., Equation (10.3)]

is [cf., Equation (10.3)]

![$\displaystyle \rho_n = R\left[1-\frac{x_n}{R}\,\sin\theta + {\cal O}\left(\frac{x_n^{\,2}}{R^{\,2}}\right)\right].$](img3369.png)

now represents the typical spacing between neighboring slits,

and assuming normally incident collimated light, Equation (10.5) generalizes to

now represents the typical spacing between neighboring slits,

and assuming normally incident collimated light, Equation (10.5) generalizes to

[which implies that

[which implies that

]. We have also employed the trigonometrical

identity

]. We have also employed the trigonometrical

identity

. (See Appendix B.)

It follows that the intensity of

the interference pattern appearing on the projection screen is specified by

. (See Appendix B.)

It follows that the intensity of

the interference pattern appearing on the projection screen is specified by

![$\displaystyle {\cal I}(\theta) \propto \langle \psi^{\,2}(\theta,t)\rangle \pro...

...um_{n=1,N} \cos\left(2\pi\,\frac{x_n}{\lambda}\,\sin\theta\right)\right]^{\,2},$](img3374.png)

.

The previous expression is a generalization of Equation (10.12).

.

The previous expression is a generalization of Equation (10.12).

![\includegraphics[width=0.9\textwidth]{Chapter10/fig10_08.eps}](img3375.png)

apart, so that

apart, so that

![$\displaystyle x_n = [n-(N+1)/2]\,d$](img3376.png)

. It follows that

. It follows that

![$\displaystyle {\cal I}(\theta) \propto \left[\sum_{n=1,N} \cos\left(2\pi\,[n-(N+1)/2]\,\frac{d}{\lambda}\,\sin\theta\right)\right]^{\,2},$](img3377.png)

is an integer. In this situation, application of l'Hopital's rule yields

is an integer. In this situation, application of l'Hopital's rule yields

. The

heights of these so-called principal maxima in the interference function are very large, being proportional to

. The

heights of these so-called principal maxima in the interference function are very large, being proportional to  , because

there is constructive

interference of the light from all

, because

there is constructive

interference of the light from all  slits. This occurs because the distances between neighboring

slits and the point on the projection screen at which a given maximum is located differ by an integer number of wavelengths; that is,

slits. This occurs because the distances between neighboring

slits and the point on the projection screen at which a given maximum is located differ by an integer number of wavelengths; that is,

. All of the principal maxima have the same height.

. All of the principal maxima have the same height.

is an integer that is not an integer multiple of

is an integer that is not an integer multiple of  . It follows that there are

. It follows that there are  zeros between neighboring

principal maxima. It can also be demonstrated that there are

zeros between neighboring

principal maxima. It can also be demonstrated that there are  secondary maxima between

neighboring principal maxima. However, these maxima are much lower in height, by a factor of order

secondary maxima between

neighboring principal maxima. However, these maxima are much lower in height, by a factor of order  , than the primary maxima.

, than the primary maxima.

, greatly exceeds the wavelength,

, greatly exceeds the wavelength,  ,

of the light (which, as we saw in Section 10.2, is the most interesting case). It can be seen that the

pattern consists of a series of bright fringes of equal intensity, separated by much wider

(relatively) dark fringes. The bright fringes correspond to the principal maxima discussed previously. As is the case for two-slit interference, the innermost (i.e., low

,

of the light (which, as we saw in Section 10.2, is the most interesting case). It can be seen that the

pattern consists of a series of bright fringes of equal intensity, separated by much wider

(relatively) dark fringes. The bright fringes correspond to the principal maxima discussed previously. As is the case for two-slit interference, the innermost (i.e., low  , small

, small  ) principal maxima are approximately equally spaced, with a characteristic angular

spacing

) principal maxima are approximately equally spaced, with a characteristic angular

spacing

. [This

result follows from Equation (10.39), and the small-angle approximation

. [This

result follows from Equation (10.39), and the small-angle approximation

.] However, the typical angular width of a principal maximum

(i.e., the angular distance between the maximum and the closest zeroes on either side of it) is

.] However, the typical angular width of a principal maximum

(i.e., the angular distance between the maximum and the closest zeroes on either side of it) is

. [This result follows from Equation (10.40), and the small-angle approximation.] The ratio of the angular width of a principal maximum to the angular spacing between successive maxima is thus

. [This result follows from Equation (10.40), and the small-angle approximation.] The ratio of the angular width of a principal maximum to the angular spacing between successive maxima is thus

identical, equally spaced, parallel scratches on one side of a thin uniform transparent glass, or plastic, film. When the film is illuminated, the scratches

strongly scatter the incident light, and effectively constitute

identical, equally spaced, parallel scratches on one side of a thin uniform transparent glass, or plastic, film. When the film is illuminated, the scratches

strongly scatter the incident light, and effectively constitute  identical, equally spaced, parallel line sources. Hence, the grating generates

the type of

identical, equally spaced, parallel line sources. Hence, the grating generates

the type of  -slit interference pattern discussed previously, with one major difference. Namely, the central (

-slit interference pattern discussed previously, with one major difference. Namely, the central ( ) principal maximum has

contributions not only from the scratches, but also from all the transparent material between the scratches. Thus, the central

principal maximum is considerably brighter than the other (

) principal maximum has

contributions not only from the scratches, but also from all the transparent material between the scratches. Thus, the central

principal maximum is considerably brighter than the other ( ) principal maxima.

) principal maxima.

-line diffraction grating that is illuminated, at normal incidence,

by a mixture of light of wavelength

-line diffraction grating that is illuminated, at normal incidence,

by a mixture of light of wavelength  , and light of wavelength

, and light of wavelength

, where

, where

. As always, the overall interference pattern (i.e., the overall wavefunction at the projection screen) produced by the grating is a linear superposition

of the pattern generated by the light of wavelength

. As always, the overall interference pattern (i.e., the overall wavefunction at the projection screen) produced by the grating is a linear superposition

of the pattern generated by the light of wavelength  , and the pattern generated by the

light of wavelength

, and the pattern generated by the

light of wavelength

. Consider the

. Consider the  th-order principal maximum associated

with the wavelength

th-order principal maximum associated

with the wavelength  interference pattern, which is located at

interference pattern, which is located at  , where

, where

. [See Equation (10.39).] Here,

. [See Equation (10.39).] Here,  is

the spacing between neighboring lines on the diffraction grating, which is assumed to be greater than

is

the spacing between neighboring lines on the diffraction grating, which is assumed to be greater than  . (Incidentally, the

width of the lines is assumed to be much less than

. (Incidentally, the

width of the lines is assumed to be much less than  .)

The maximum in question has a finite angular width.

We can determine this width by locating the zeros in the interference pattern on either side of the maximum. Let the zeros

be

located at

.)

The maximum in question has a finite angular width.

We can determine this width by locating the zeros in the interference pattern on either side of the maximum. Let the zeros

be

located at

.

The maximum itself corresponds to

.

The maximum itself corresponds to

. Hence, the

zeros correspond to

. Hence, the

zeros correspond to

(i.e.,

they correspond to the first zeros of the function

(i.e.,

they correspond to the first zeros of the function

![$\sin[\pi\,N\,(d/\lambda)\,\sin\theta]$](img3396.png) on either side of the zero at

on either side of the zero at  .) [See Equation (10.38).]

Taylor expanding to first order in

.) [See Equation (10.38).]

Taylor expanding to first order in

, we obtain

, we obtain

to

to

.

Consider the

.

Consider the  th-order principal maximum associated with the wavelength

th-order principal maximum associated with the wavelength

interference pattern, which is

located at

interference pattern, which is

located at

, where

, where

. [See Equation (10.39).] Taylor

expanding to first order in

. [See Equation (10.39).] Taylor

expanding to first order in

, we obtain

, we obtain

th spectral order, the angular spacing,

th spectral order, the angular spacing,

, between the

, between the

th-order maxima associated with these two wavelengths must be greater than the angular widths,

th-order maxima associated with these two wavelengths must be greater than the angular widths,

, of the

maxima themselves. If this is the case then the overall

, of the

maxima themselves. If this is the case then the overall  th-order maximum will consist of two closely spaced maxima, or “spectral lines” (centered at

th-order maximum will consist of two closely spaced maxima, or “spectral lines” (centered at  and

and

). On the other hand, if this is not the case then the two maxima will merge to form a single maximum, and it will

consequently not be possible to tell that the incident light consists of a mixture of two different wavelengths. Thus, the condition

for the spectroscope to be able to resolve the spectral lines at the

). On the other hand, if this is not the case then the two maxima will merge to form a single maximum, and it will

consequently not be possible to tell that the incident light consists of a mixture of two different wavelengths. Thus, the condition

for the spectroscope to be able to resolve the spectral lines at the  th spectral order is

th spectral order is

, or

, or

) increases, and also as the spectral order (i.e.,

) increases, and also as the spectral order (i.e.,  ) increases. Incidentally, there

is no resolving power at the lowest (i.e.,

) increases. Incidentally, there

is no resolving power at the lowest (i.e.,  ) spectral order, because the corresponding principal maximum is located at

) spectral order, because the corresponding principal maximum is located at  irrespective of the wavelength of the incident light. Moreover, there is a limit to how large

irrespective of the wavelength of the incident light. Moreover, there is a limit to how large  can become (i.e., a given diffraction

grating, illuminated by light of a given wavelength, has a finite number of principal maxima). This follows because

can become (i.e., a given diffraction

grating, illuminated by light of a given wavelength, has a finite number of principal maxima). This follows because

cannot

exceed unity, so, according to Equation (10.39),

cannot

exceed unity, so, according to Equation (10.39),  cannot exceed

cannot exceed  .

.