Next: Waveguides Up: Dispersive Waves Previous: Perpendicular EM Waves in Contents

|

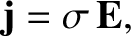

(9.200) |

is the current density (i.e., the current per unit area),

is the current density (i.e., the current per unit area),  the

electric field-strength, and

the

electric field-strength, and  a constant known as the electrical conductivity

of the medium in question.

The

a constant known as the electrical conductivity

of the medium in question.

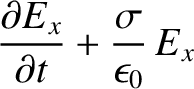

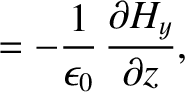

The  -directed propagation of a plane electromagnetic

wave, linearly polarized in the

-directed propagation of a plane electromagnetic

wave, linearly polarized in the  -direction, through an Ohmic conductor of conductivity

-direction, through an Ohmic conductor of conductivity  is

governed by (see Appendix C)

is

governed by (see Appendix C)

|

|

(9.201) |

|

|

(9.202) |

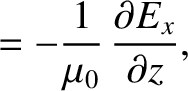

, the first term on the

left-hand side of Equation (9.201) is negligible with respect to the

second term, and the previous two equations reduce to

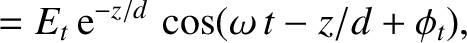

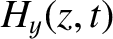

These equations can be solved to give

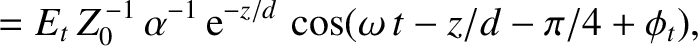

where

and

(See Exercise 7.)

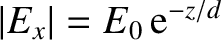

Equations (9.205) and (9.206) indicate that the amplitude of an electromagnetic

wave propagating through a conductor decays exponentially on a characteristic lengthscale,

, the first term on the

left-hand side of Equation (9.201) is negligible with respect to the

second term, and the previous two equations reduce to

These equations can be solved to give

where

and

(See Exercise 7.)

Equations (9.205) and (9.206) indicate that the amplitude of an electromagnetic

wave propagating through a conductor decays exponentially on a characteristic lengthscale,

, that is known as the skin-depth. Consequently, an electromagnetic wave

cannot penetrate more than a few skin-depths into a conducting medium. The skin-depth

is smaller at higher frequencies. This implies that high-frequency waves penetrate

a shorter distance into a conductor than low-frequency waves.

, that is known as the skin-depth. Consequently, an electromagnetic wave

cannot penetrate more than a few skin-depths into a conducting medium. The skin-depth

is smaller at higher frequencies. This implies that high-frequency waves penetrate

a shorter distance into a conductor than low-frequency waves.

Consider a typical metallic conductor such as copper, whose electrical

conductivity at room temperature is about

(Wikipedia contributors 2018). Copper, therefore, acts as a good

conductor for all electromagnetic waves of frequency below about

(Wikipedia contributors 2018). Copper, therefore, acts as a good

conductor for all electromagnetic waves of frequency below about

. The skin-depth in copper for such waves is thus

. The skin-depth in copper for such waves is thus

|

(9.209) |

at 1 Hz, but only about

2 mm at 1 kHz. This gives rise to the so-called skin effect in copper wires, by which an oscillating electromagnetic

signal of increasing frequency, transmitted along such a wire, is confined

to an increasingly narrow layer (whose thickness is of order of the skin-depth)

on the surface of the wire.

at 1 Hz, but only about

2 mm at 1 kHz. This gives rise to the so-called skin effect in copper wires, by which an oscillating electromagnetic

signal of increasing frequency, transmitted along such a wire, is confined

to an increasingly narrow layer (whose thickness is of order of the skin-depth)

on the surface of the wire.

The conductivity of sea-water is only about

(Wikipedia contributors 2018). However, this is still sufficiently high for sea-water to act as

a good conductor for all radio frequency electromagnetic waves (i.e.,

(Wikipedia contributors 2018). However, this is still sufficiently high for sea-water to act as

a good conductor for all radio frequency electromagnetic waves (i.e.,

GHz). The skin-depth at 1 MHz (

GHz). The skin-depth at 1 MHz (

m)

is about

m)

is about  m, whereas that at 1 kHz (

m, whereas that at 1 kHz (

km)

is still only about 7 m. This obviously poses quite severe restrictions for

radio communication with submerged submarines. Either the submarines

have to come quite close to the surface to communicate (which is dangerous), or the communication must be performed with extremely low-frequency (ELF) waves (i.e.,

km)

is still only about 7 m. This obviously poses quite severe restrictions for

radio communication with submerged submarines. Either the submarines

have to come quite close to the surface to communicate (which is dangerous), or the communication must be performed with extremely low-frequency (ELF) waves (i.e.,  Hz). Unfortunately, such waves have very large wavelengths (

Hz). Unfortunately, such waves have very large wavelengths (

), which means

that they can only be efficiently generated by gigantic

antennas.

), which means

that they can only be efficiently generated by gigantic

antennas.

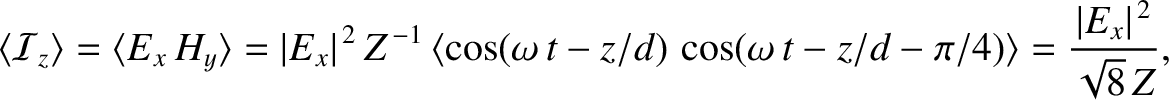

According to Equation (9.206), the phase of the magnetic component of an

electromagnetic wave propagating through a good conductor lags behind that of the

electric component by  radians. It follows that the mean energy flux into

the conductor takes the form (see Appendix C)

radians. It follows that the mean energy flux into

the conductor takes the form (see Appendix C)

|

(9.210) |

is the amplitude of the electric component of the

wave. The fact that the mean energy flux is positive indicates that some of the

wave energy is absorbed by the conductor. In fact, the absorbed energy corresponds

to the energy lost due to Joule heating within the conductor. (See Exercise 15.)

is the amplitude of the electric component of the

wave. The fact that the mean energy flux is positive indicates that some of the

wave energy is absorbed by the conductor. In fact, the absorbed energy corresponds

to the energy lost due to Joule heating within the conductor. (See Exercise 15.)

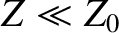

According to Equation (9.208), the impedance of a good conductor is far less than

that of a vacuum (i.e.,  ). This implies that the ratio of the magnetic

to the electric components of an electromagnetic wave propagating through a good conductor is far larger than that of a wave propagating through a vacuum. (This is because the conductor effectively “shorts out" the electric component of the wave.)

). This implies that the ratio of the magnetic

to the electric components of an electromagnetic wave propagating through a good conductor is far larger than that of a wave propagating through a vacuum. (This is because the conductor effectively “shorts out" the electric component of the wave.)

Suppose that the region  is a vacuum, and the region

is a vacuum, and the region  is

occupied by a good conductor of conductivity

is

occupied by a good conductor of conductivity  . Consider a linearly polarized plane wave,

normally incident on the interface. Let the wave electric and

magnetic fields in the vacuum region take the form of the incident and reflected waves specified in Equations (9.42) and (9.43).

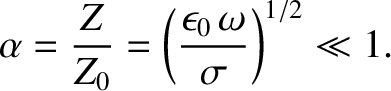

The wave electric and magnetic fields in the conductor are written

. Consider a linearly polarized plane wave,

normally incident on the interface. Let the wave electric and

magnetic fields in the vacuum region take the form of the incident and reflected waves specified in Equations (9.42) and (9.43).

The wave electric and magnetic fields in the conductor are written

|

|

(9.211) |

|

|

(9.212) |

is the amplitude of the evanescent wave that penetrates into the

conductor,

is the amplitude of the evanescent wave that penetrates into the

conductor,  is the phase of this wave with respect to the incident wave,

and

is the phase of this wave with respect to the incident wave,

and

|

(9.213) |

and

and  at the vacuum/conductor interface (

at the vacuum/conductor interface ( ). (See Appendix C.)

In other words,

Equations (9.214) and (9.215), which must be satisfied at all times,

can be solved, in the limit

). (See Appendix C.)

In other words,

Equations (9.214) and (9.215), which must be satisfied at all times,

can be solved, in the limit

, to give

(See Exercise 8.)

Hence, the coefficient of reflection becomes

, to give

(See Exercise 8.)

Hence, the coefficient of reflection becomes

According to the previous analysis, a good conductor reflects a normally incident

electromagnetic wave with a phase shift of almost  radians (i.e.,

radians (i.e.,

). The coefficient of reflection is just less than unity, indicating that, while most

of the incident energy is reflected by the conductor, a small fraction of it

is absorbed.

). The coefficient of reflection is just less than unity, indicating that, while most

of the incident energy is reflected by the conductor, a small fraction of it

is absorbed.

High-quality metallic mirrors are generally coated in silver, whose conductivity

is

(Wikipedia contributors 2018). It follows, from Equation (9.220), that at optical

frequencies (

(Wikipedia contributors 2018). It follows, from Equation (9.220), that at optical

frequencies (

) the coefficient

of reflection of a silvered mirror is

) the coefficient

of reflection of a silvered mirror is

. This implies that

about

. This implies that

about  of the light incident on the mirror is absorbed, rather than being reflected. This rather severe light loss can be

problematic in instruments, such as astronomical telescopes, that are used to

view faint objects.

of the light incident on the mirror is absorbed, rather than being reflected. This rather severe light loss can be

problematic in instruments, such as astronomical telescopes, that are used to

view faint objects.