Sound Waves in Fluids

Consider a uniform fluid (at rest) whose equilibrium density and pressure

are  and

and  , respectively. Suppose that a sound wave propagates though the fluid, and that the density

and pressure perturbations produced by the wave are

, respectively. Suppose that a sound wave propagates though the fluid, and that the density

and pressure perturbations produced by the wave are

and

and  , respectively. Incidentally, the quantity

, respectively. Incidentally, the quantity  is

often referred to as the acoustic pressure. In two

dimensions (i.e., neglecting any variation of perturbed quantities in the

is

often referred to as the acoustic pressure. In two

dimensions (i.e., neglecting any variation of perturbed quantities in the  -direction), the equations governing the propagation of

a sound wave though a uniform fluid are (Landau and Lifshitz 1959)

(See Section 9.12 for a more complete discussion of fluid equations.)

Here,

-direction), the equations governing the propagation of

a sound wave though a uniform fluid are (Landau and Lifshitz 1959)

(See Section 9.12 for a more complete discussion of fluid equations.)

Here,

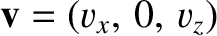

is the perturbation to the fluid velocity produced by the wave, and

is the perturbation to the fluid velocity produced by the wave, and

|

(7.194) |

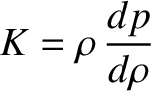

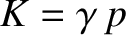

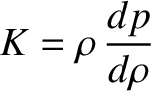

is the bulk modulus. The bulk modulus is a quantity with the units of

pressure that measures a given substance's resistance to uniform compression. The bulk modulus of an ideal

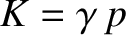

gas is  , where

, where  is the ratio of specific heats. On the other hand, the bulk modulus of

water at

is the ratio of specific heats. On the other hand, the bulk modulus of

water at

is

is

(Wikipedia contributors 2018).

(Wikipedia contributors 2018).

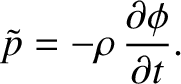

It is helpful to write

where

is conventionally referred to as a velocity potential.

It follows from Equations (7.192) and (7.193) that

is conventionally referred to as a velocity potential.

It follows from Equations (7.192) and (7.193) that

|

(7.197) |

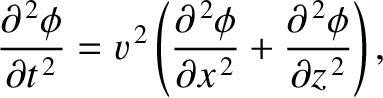

Moreover, substitution into Equation (7.194) yields the wave equation

|

(7.198) |

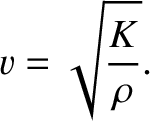

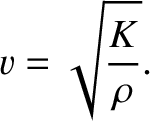

where the characteristic wave speed is

|

(7.199) |

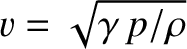

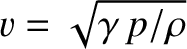

For the case of an ideal gas, for which

, we obtain

, we obtain

. (See Section 5.4.) On the other hand, for

the case of water at

. (See Section 5.4.) On the other hand, for

the case of water at

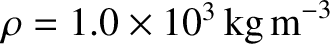

, for which

, for which

and

and

,

we get

,

we get

. This prediction is in good agreement with the measured sound speed in water

at

. This prediction is in good agreement with the measured sound speed in water

at

, which is

, which is

(Wikipedia contributors 2018).

(Wikipedia contributors 2018).

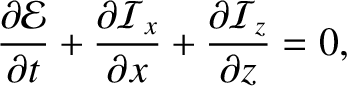

Forming the sum of  times Equation (7.192),

times Equation (7.192),  times Equation (7.193), and

times Equation (7.193), and

times Equation (7.194), we obtain

times Equation (7.194), we obtain

|

(7.200) |

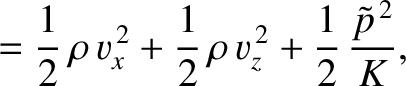

where

Equation (7.201) can be recognized as a two-dimensional energy conservation equation. (See Section 6.5.)

Here,  is the acoustic energy density, and

is the acoustic energy density, and

and

and

are the acoustic energy fluxes

in the

are the acoustic energy fluxes

in the  - and

- and  -directions, respectively.

-directions, respectively.

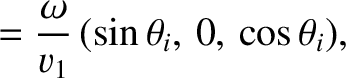

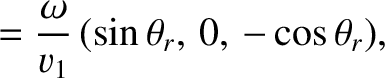

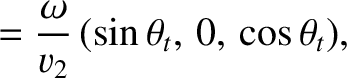

Consider a situation (analogous to that illustrated in Figure 7.7) in which a sound wave is incident at an

interface between two uniform immiscible fluids. Let the region  be occupied by a fluid of equilibrium density

be occupied by a fluid of equilibrium density  and sound speed

and sound speed  , and let the region

, and let the region  be occupied by a fluid of equilibrium density

be occupied by a fluid of equilibrium density  and

sound speed

and

sound speed  . We can write the wavevectors of the incident, reflected, and refracted waves as

. We can write the wavevectors of the incident, reflected, and refracted waves as

respectively. Here, for the sake of simplicity, we have assumed that all three wavevectors lie in the same plane (as is

readily demonstrated; see Section 7.8.) Moreover, in order to be valid solutions of the wave equation, (7.199), all three waves must

satisfy the dispersion

relation

, where

, where  is the common wave frequency. Finally,

is the common wave frequency. Finally,  ,

,  , and

, and  are

the angles of incidence, reflection, and refraction, respectively. (See Section 7.8.)

are

the angles of incidence, reflection, and refraction, respectively. (See Section 7.8.)

The velocity potential in the region  is written

is written

where the first and second terms on the right-hand side specify the incident and reflected waves, respectively.

The velocity potential in the region  takes the form

takes the form

![$\displaystyle \phi(x,z,t) = \phi_t\,\cos[\omega\,(t-\sin\theta_t\,x/v_2-\cos\theta_t\,z/v_2)],$](img2266.png) |

(7.208) |

where the term on the right-hand side specifies the refracted wave.

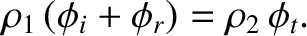

The first physical matching constraint that must be satisfied at the interface is continuity of the acoustic pressure; that is,

![$\displaystyle [\tilde{p}]_{z=0_-}^{z=0_+}=-\left[\rho\,\frac{\partial\phi}{\partial t}\right]_{z=0_-}^{z=0_+}=0.$](img2267.png) |

(7.209) |

This contraint yields

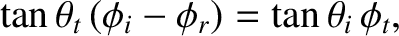

The previous equation holds at all values of  . This is only possible if

These two expressions are analogous to the laws of reflection and refraction, respectively, of geometric optics. (See Section 7.8.)

This suggests that these laws are of universal validity, rather than being restricted to light waves. Equation (7.211) reduces to

. This is only possible if

These two expressions are analogous to the laws of reflection and refraction, respectively, of geometric optics. (See Section 7.8.)

This suggests that these laws are of universal validity, rather than being restricted to light waves. Equation (7.211) reduces to

|

(7.212) |

The second physical matching constraint that must be satisfied at the interface is continuity of the

normal velocity; that is,

![$\displaystyle [v_z]_{z=0_-}^{z=0_+} = \left[\frac{\partial\phi}{\partial z}\right]_{z=0_-}^{z=0_+} = 0.$](img2274.png) |

(7.213) |

This constraint yields

|

(7.214) |

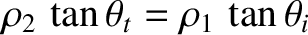

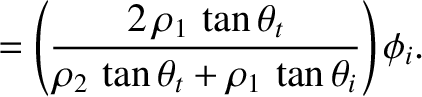

where use has been made of Equation (7.213). Equations (7.214) and (7.216) can be combined to give

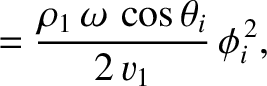

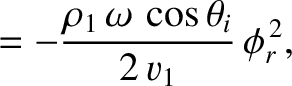

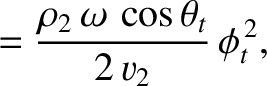

Equations (7.197), (7.198), and (7.204) reveal that the mean acoustic energy fluxes, normal

to the interface, associated with the incident, reflected, and refracted waves are

respectively. Thus, it follows that the coefficients of reflection and transmission at the interface

are

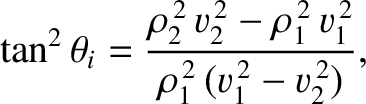

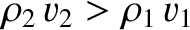

respectively. It is actually possible for there to be no reflection at the interface (i.e.,  ), provided that

), provided that

.

This criterion yields

.

This criterion yields

|

(7.222) |

which can only be satisfied if

and

and  , or if

, or if

and

and  .

The critical angle of incidence at which there is no reflection is sometimes called the angle of intromission.

However, not every pair of immiscible fluids possesses such an angle.

.

The critical angle of incidence at which there is no reflection is sometimes called the angle of intromission.

However, not every pair of immiscible fluids possesses such an angle.

and

and  , respectively. Suppose that a sound wave propagates though the fluid, and that the density

and pressure perturbations produced by the wave are

, respectively. Suppose that a sound wave propagates though the fluid, and that the density

and pressure perturbations produced by the wave are

and

and  , respectively. Incidentally, the quantity

, respectively. Incidentally, the quantity  is

often referred to as the acoustic pressure. In two

dimensions (i.e., neglecting any variation of perturbed quantities in the

is

often referred to as the acoustic pressure. In two

dimensions (i.e., neglecting any variation of perturbed quantities in the  -direction), the equations governing the propagation of

a sound wave though a uniform fluid are (Landau and Lifshitz 1959)

(See Section 9.12 for a more complete discussion of fluid equations.)

Here,

-direction), the equations governing the propagation of

a sound wave though a uniform fluid are (Landau and Lifshitz 1959)

(See Section 9.12 for a more complete discussion of fluid equations.)

Here,

is the perturbation to the fluid velocity produced by the wave, and

is the perturbation to the fluid velocity produced by the wave, and

, where

, where  is the ratio of specific heats. On the other hand, the bulk modulus of

water at

is the ratio of specific heats. On the other hand, the bulk modulus of

water at

is

is

(Wikipedia contributors 2018).

(Wikipedia contributors 2018).

is conventionally referred to as a velocity potential.

It follows from Equations (7.192) and (7.193) that

Moreover, substitution into Equation (7.194) yields the wave equation

where the characteristic wave speed is

is conventionally referred to as a velocity potential.

It follows from Equations (7.192) and (7.193) that

Moreover, substitution into Equation (7.194) yields the wave equation

where the characteristic wave speed is

, we obtain

, we obtain

. (See Section 5.4.) On the other hand, for

the case of water at

. (See Section 5.4.) On the other hand, for

the case of water at

, for which

, for which

and

and

,

we get

,

we get

. This prediction is in good agreement with the measured sound speed in water

at

. This prediction is in good agreement with the measured sound speed in water

at

, which is

, which is

(Wikipedia contributors 2018).

(Wikipedia contributors 2018).

times Equation (7.192),

times Equation (7.192),  times Equation (7.193), and

times Equation (7.193), and

times Equation (7.194), we obtain

times Equation (7.194), we obtain

is the acoustic energy density, and

is the acoustic energy density, and

and

and

are the acoustic energy fluxes

in the

are the acoustic energy fluxes

in the  - and

- and  -directions, respectively.

-directions, respectively.

be occupied by a fluid of equilibrium density

be occupied by a fluid of equilibrium density  and sound speed

and sound speed  , and let the region

, and let the region  be occupied by a fluid of equilibrium density

be occupied by a fluid of equilibrium density  and

sound speed

and

sound speed  . We can write the wavevectors of the incident, reflected, and refracted waves as

. We can write the wavevectors of the incident, reflected, and refracted waves as

, where

, where  is the common wave frequency. Finally,

is the common wave frequency. Finally,  ,

,  , and

, and  are

the angles of incidence, reflection, and refraction, respectively. (See Section 7.8.)

are

the angles of incidence, reflection, and refraction, respectively. (See Section 7.8.)

is written

is written

![$\displaystyle = \phi_i\,\cos[\omega\,(t-\sin\theta_i\,x/v_1-\cos\theta_i\,z/v_1)]$](img2264.png)

![$\displaystyle ~~~~+\phi_r\,\cos[\omega\,(t-\sin\theta_r\,x/v_1+\cos\theta_r\,z/v_1)],$](img2265.png)

takes the form

takes the form

![$\displaystyle \phi(x,z,t) = \phi_t\,\cos[\omega\,(t-\sin\theta_t\,x/v_2-\cos\theta_t\,z/v_2)],$](img2266.png)

![$\displaystyle [\tilde{p}]_{z=0_-}^{z=0_+}=-\left[\rho\,\frac{\partial\phi}{\partial t}\right]_{z=0_-}^{z=0_+}=0.$](img2267.png)

. This is only possible if

. This is only possible if

![$\displaystyle [v_z]_{z=0_-}^{z=0_+} = \left[\frac{\partial\phi}{\partial z}\right]_{z=0_-}^{z=0_+} = 0.$](img2274.png)

), provided that

), provided that

.

This criterion yields

which can only be satisfied if

.

This criterion yields

which can only be satisfied if

and

and  , or if

, or if

and

and  .

The critical angle of incidence at which there is no reflection is sometimes called the angle of intromission.

However, not every pair of immiscible fluids possesses such an angle.

.

The critical angle of incidence at which there is no reflection is sometimes called the angle of intromission.

However, not every pair of immiscible fluids possesses such an angle.