Sound Waves in Ideal Gas

Consider a uniform ideal gas of equilibrium mass density  and equilibrium pressure

and equilibrium pressure  . Let us

investigate the longitudinal oscillations of such a gas. Such oscillations

are known as sound waves. Generally speaking, a sound wave

in an ideal gas

oscillates sufficiently rapidly that heat is unable to flow fast enough to smooth out any

temperature perturbations generated by the wave. Under these circumstances,

the gas obeys the adiabatic gas law (Reif 2008),

. Let us

investigate the longitudinal oscillations of such a gas. Such oscillations

are known as sound waves. Generally speaking, a sound wave

in an ideal gas

oscillates sufficiently rapidly that heat is unable to flow fast enough to smooth out any

temperature perturbations generated by the wave. Under these circumstances,

the gas obeys the adiabatic gas law (Reif 2008),

|

(5.31) |

where  is the pressure,

is the pressure,  the volume, and

the volume, and  the ratio of specific

heats (i.e., the ratio of the gas's specific heat at constant pressure to its

specific heat at constant volume) (ibid.). This ratio is

the ratio of specific

heats (i.e., the ratio of the gas's specific heat at constant pressure to its

specific heat at constant volume) (ibid.). This ratio is  for ordinary air (Haynes and Lide 2011b).

for ordinary air (Haynes and Lide 2011b).

Consider a sound wave in a column of gas of cross-sectional area  . Let

. Let  measure distance along the column. Suppose that the wave generates an

measure distance along the column. Suppose that the wave generates an

-directed displacement of the column,

-directed displacement of the column,  . Consider a small section of

the column lying between

. Consider a small section of

the column lying between

and

and

. The change in volume

of the section is

. The change in volume

of the section is

![$\delta V = A\,[\psi(x+\delta x/2,t)-\psi(x-\delta x/2,t)]$](img1220.png) .

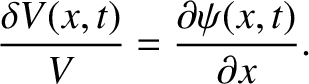

Hence, the relative change in volume, which is assumed to be small compared to unity, is

.

Hence, the relative change in volume, which is assumed to be small compared to unity, is

![$\displaystyle \frac{\delta V}{V} = \frac{A\,[\psi(x+\delta x/2,t)-\psi(x-\delta x/2,t)]}{A\,\delta x}.$](img1221.png) |

(5.32) |

In the limit

, this becomes

, this becomes

|

(5.33) |

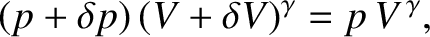

The pressure perturbation

associated with the volume perturbation

associated with the volume perturbation

follows

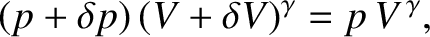

from Equation (5.31), which yields

follows

from Equation (5.31), which yields

|

(5.34) |

or

|

(5.35) |

giving

|

(5.36) |

where use has been made of Equation (5.33). Here, we have neglected terms that are second order, or higher,

in the small quantities

and

and

.

.

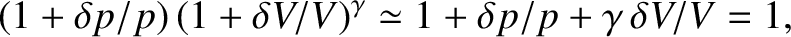

Consider a section of the gas column lying between

and

and

. The mass of this section is

. The mass of this section is

. The

. The  -directed

force acting on its left boundary is

-directed

force acting on its left boundary is

![$A\,[p+\delta p(x-\delta x/2,t)]$](img1230.png) , whereas the

, whereas the

-directed force acting on its right boundary is

-directed force acting on its right boundary is

![$-A\,[p+\delta p(x+\delta x/2,t)]$](img1231.png) .

Finally, the average longitudinal (i.e.,

.

Finally, the average longitudinal (i.e.,  -directed) acceleration of the section is

-directed) acceleration of the section is

.

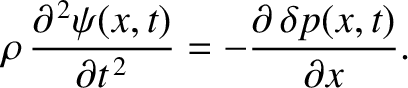

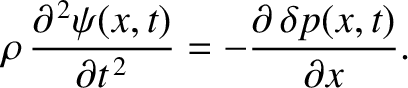

Thus, the section's longitudinal equation of motion is written

.

Thus, the section's longitudinal equation of motion is written

![$\displaystyle \rho\,A\,\delta x\,\frac{\partial^{\,2}\psi(x,t)}{\partial t^{\,2}} = -A\left[\delta p(x+\delta x/2,t)-\delta p(x-\delta x/2,t)\right].$](img1232.png) |

(5.37) |

In the limit

, this equation reduces to

, this equation reduces to

|

(5.38) |

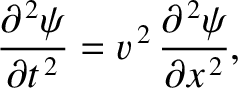

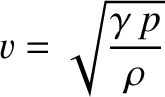

Finally, Equation (5.36) yields

|

(5.39) |

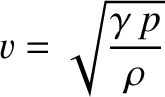

where

|

(5.40) |

is a constant with the dimensions of velocity, which

turns out to be the sound speed in the gas. (See Section 6.2.)

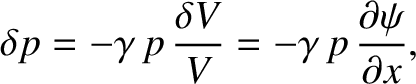

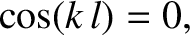

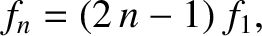

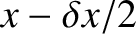

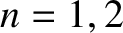

Figure 5.5:

First three normal modes of an organ pipe with one open end. The plots show contours of the magnitude of the

pressure perturbation associated with each mode. Dark/light contours correspond to high/low magnitude.

|

|

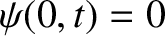

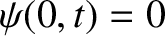

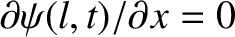

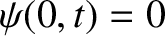

As an example, suppose that a standing wave is excited in a uniform organ pipe of length  .

Let the closed end of the pipe lie at

.

Let the closed end of the pipe lie at  , and the open end at

, and the open end at  .

The standing wave satisfies the wave equation (5.39), where

.

The standing wave satisfies the wave equation (5.39), where  represents the

speed of sound in air. The boundary conditions are that

represents the

speed of sound in air. The boundary conditions are that

—that is, there is

zero longitudinal displacement of the air at the closed end of the pipe—and

—that is, there is

zero longitudinal displacement of the air at the closed end of the pipe—and

—that is, there is zero pressure perturbation at the open end of the pipe (because the small pressure perturbation in the pipe is not

intense enough to modify the pressure of the atmosphere external to the pipe).

Let us write the displacement pattern associated with the standing wave in the form

—that is, there is zero pressure perturbation at the open end of the pipe (because the small pressure perturbation in the pipe is not

intense enough to modify the pressure of the atmosphere external to the pipe).

Let us write the displacement pattern associated with the standing wave in the form

|

(5.41) |

where  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are constants.

This expression automatically satisfies the boundary condition

are constants.

This expression automatically satisfies the boundary condition

.

The other boundary condition is satisfied provided

.

The other boundary condition is satisfied provided

|

(5.42) |

which yields

|

(5.43) |

where the mode number  is a positive integer. Equations (5.39) and (5.41) give the dispersion relation

is a positive integer. Equations (5.39) and (5.41) give the dispersion relation

|

(5.44) |

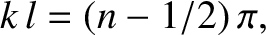

Hence, the  th normal mode has a wavelength

th normal mode has a wavelength

|

(5.45) |

and an oscillation frequency (in hertz)

|

(5.46) |

where

is the frequency of the fundamental harmonic (i.e., the normal

mode with the lowest oscillation frequency). Figure 5.5 illustrates the

characteristic displacement patterns and oscillation frequencies of the pipe's first

three normal modes (i.e.,

is the frequency of the fundamental harmonic (i.e., the normal

mode with the lowest oscillation frequency). Figure 5.5 illustrates the

characteristic displacement patterns and oscillation frequencies of the pipe's first

three normal modes (i.e.,  , and 3). In fact, the figure plots the magnitude of the pressure perturbation

associated with each mode.

It can be seen that the modes all

have an anti-node in the pressure (which corresponds to a node in the displacement, and vice versa) at the closed end of the pipe, and a node at the open end. The

fundamental harmonic has a wavelength that is four times the length of the pipe.

The first overtone harmonic has a wavelength that is

, and 3). In fact, the figure plots the magnitude of the pressure perturbation

associated with each mode.

It can be seen that the modes all

have an anti-node in the pressure (which corresponds to a node in the displacement, and vice versa) at the closed end of the pipe, and a node at the open end. The

fundamental harmonic has a wavelength that is four times the length of the pipe.

The first overtone harmonic has a wavelength that is  rds the length of the pipe, and a frequency that is three times that of the fundamental. Finally, the second overtone

has a wavelength that is

rds the length of the pipe, and a frequency that is three times that of the fundamental. Finally, the second overtone

has a wavelength that is  ths the length of the pipe, and a frequency

that is five times that of the fundamental. By contrast, the normal modes

of a guitar string have nodes at either end of the string. (See Figure 4.6.)

Thus, the fundamental harmonic has a wavelength that

is twice the length of the string. The first overtone harmonic has a wavelength that

is the length of the string, and a frequency that is twice that of the fundamental. Finally, the second overtone harmonic has a wavelength that is

ths the length of the pipe, and a frequency

that is five times that of the fundamental. By contrast, the normal modes

of a guitar string have nodes at either end of the string. (See Figure 4.6.)

Thus, the fundamental harmonic has a wavelength that

is twice the length of the string. The first overtone harmonic has a wavelength that

is the length of the string, and a frequency that is twice that of the fundamental. Finally, the second overtone harmonic has a wavelength that is  rds the length of the

string, and a frequency that is three times that of the fundamental.

rds the length of the

string, and a frequency that is three times that of the fundamental.

and equilibrium pressure

and equilibrium pressure  . Let us

investigate the longitudinal oscillations of such a gas. Such oscillations

are known as sound waves. Generally speaking, a sound wave

in an ideal gas

oscillates sufficiently rapidly that heat is unable to flow fast enough to smooth out any

temperature perturbations generated by the wave. Under these circumstances,

the gas obeys the adiabatic gas law (Reif 2008),

where

. Let us

investigate the longitudinal oscillations of such a gas. Such oscillations

are known as sound waves. Generally speaking, a sound wave

in an ideal gas

oscillates sufficiently rapidly that heat is unable to flow fast enough to smooth out any

temperature perturbations generated by the wave. Under these circumstances,

the gas obeys the adiabatic gas law (Reif 2008),

where  is the pressure,

is the pressure,  the volume, and

the volume, and  the ratio of specific

heats (i.e., the ratio of the gas's specific heat at constant pressure to its

specific heat at constant volume) (ibid.). This ratio is

the ratio of specific

heats (i.e., the ratio of the gas's specific heat at constant pressure to its

specific heat at constant volume) (ibid.). This ratio is  for ordinary air (Haynes and Lide 2011b).

for ordinary air (Haynes and Lide 2011b).

. Let

. Let  measure distance along the column. Suppose that the wave generates an

measure distance along the column. Suppose that the wave generates an

-directed displacement of the column,

-directed displacement of the column,  . Consider a small section of

the column lying between

. Consider a small section of

the column lying between

and

and

. The change in volume

of the section is

. The change in volume

of the section is

![$\delta V = A\,[\psi(x+\delta x/2,t)-\psi(x-\delta x/2,t)]$](img1220.png) .

Hence, the relative change in volume, which is assumed to be small compared to unity, is

.

Hence, the relative change in volume, which is assumed to be small compared to unity, is

![$\displaystyle \frac{\delta V}{V} = \frac{A\,[\psi(x+\delta x/2,t)-\psi(x-\delta x/2,t)]}{A\,\delta x}.$](img1221.png)

, this becomes

The pressure perturbation

, this becomes

The pressure perturbation

associated with the volume perturbation

associated with the volume perturbation

follows

from Equation (5.31), which yields

follows

from Equation (5.31), which yields

and

and

.

.

and

and

. The mass of this section is

. The mass of this section is

. The

. The  -directed

force acting on its left boundary is

-directed

force acting on its left boundary is

![$A\,[p+\delta p(x-\delta x/2,t)]$](img1230.png) , whereas the

, whereas the

-directed force acting on its right boundary is

-directed force acting on its right boundary is

![$-A\,[p+\delta p(x+\delta x/2,t)]$](img1231.png) .

Finally, the average longitudinal (i.e.,

.

Finally, the average longitudinal (i.e.,  -directed) acceleration of the section is

-directed) acceleration of the section is

.

Thus, the section's longitudinal equation of motion is written

.

Thus, the section's longitudinal equation of motion is written

![$\displaystyle \rho\,A\,\delta x\,\frac{\partial^{\,2}\psi(x,t)}{\partial t^{\,2}} = -A\left[\delta p(x+\delta x/2,t)-\delta p(x-\delta x/2,t)\right].$](img1232.png)

, this equation reduces to

, this equation reduces to

![\includegraphics[width=1.4\textwidth]{Chapter05/fig5_05.eps}](img1235.png)

.

Let the closed end of the pipe lie at

.

Let the closed end of the pipe lie at  , and the open end at

, and the open end at  .

The standing wave satisfies the wave equation (5.39), where

.

The standing wave satisfies the wave equation (5.39), where  represents the

speed of sound in air. The boundary conditions are that

represents the

speed of sound in air. The boundary conditions are that

—that is, there is

zero longitudinal displacement of the air at the closed end of the pipe—and

—that is, there is

zero longitudinal displacement of the air at the closed end of the pipe—and

—that is, there is zero pressure perturbation at the open end of the pipe (because the small pressure perturbation in the pipe is not

intense enough to modify the pressure of the atmosphere external to the pipe).

Let us write the displacement pattern associated with the standing wave in the form

—that is, there is zero pressure perturbation at the open end of the pipe (because the small pressure perturbation in the pipe is not

intense enough to modify the pressure of the atmosphere external to the pipe).

Let us write the displacement pattern associated with the standing wave in the form

,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are constants.

This expression automatically satisfies the boundary condition

are constants.

This expression automatically satisfies the boundary condition

.

The other boundary condition is satisfied provided

.

The other boundary condition is satisfied provided

is a positive integer. Equations (5.39) and (5.41) give the dispersion relation

is a positive integer. Equations (5.39) and (5.41) give the dispersion relation

th normal mode has a wavelength

th normal mode has a wavelength

is the frequency of the fundamental harmonic (i.e., the normal

mode with the lowest oscillation frequency). Figure 5.5 illustrates the

characteristic displacement patterns and oscillation frequencies of the pipe's first

three normal modes (i.e.,

is the frequency of the fundamental harmonic (i.e., the normal

mode with the lowest oscillation frequency). Figure 5.5 illustrates the

characteristic displacement patterns and oscillation frequencies of the pipe's first

three normal modes (i.e.,  , and 3). In fact, the figure plots the magnitude of the pressure perturbation

associated with each mode.

It can be seen that the modes all

have an anti-node in the pressure (which corresponds to a node in the displacement, and vice versa) at the closed end of the pipe, and a node at the open end. The

fundamental harmonic has a wavelength that is four times the length of the pipe.

The first overtone harmonic has a wavelength that is

, and 3). In fact, the figure plots the magnitude of the pressure perturbation

associated with each mode.

It can be seen that the modes all

have an anti-node in the pressure (which corresponds to a node in the displacement, and vice versa) at the closed end of the pipe, and a node at the open end. The

fundamental harmonic has a wavelength that is four times the length of the pipe.

The first overtone harmonic has a wavelength that is  rds the length of the pipe, and a frequency that is three times that of the fundamental. Finally, the second overtone

has a wavelength that is

rds the length of the pipe, and a frequency that is three times that of the fundamental. Finally, the second overtone

has a wavelength that is  ths the length of the pipe, and a frequency

that is five times that of the fundamental. By contrast, the normal modes

of a guitar string have nodes at either end of the string. (See Figure 4.6.)

Thus, the fundamental harmonic has a wavelength that

is twice the length of the string. The first overtone harmonic has a wavelength that

is the length of the string, and a frequency that is twice that of the fundamental. Finally, the second overtone harmonic has a wavelength that is

ths the length of the pipe, and a frequency

that is five times that of the fundamental. By contrast, the normal modes

of a guitar string have nodes at either end of the string. (See Figure 4.6.)

Thus, the fundamental harmonic has a wavelength that

is twice the length of the string. The first overtone harmonic has a wavelength that

is the length of the string, and a frequency that is twice that of the fundamental. Finally, the second overtone harmonic has a wavelength that is  rds the length of the

string, and a frequency that is three times that of the fundamental.

rds the length of the

string, and a frequency that is three times that of the fundamental.