Longitudinal Waves on Thin Elastic Rod

Consider a thin uniform elastic rod of length  and cross-sectional area

and cross-sectional area  .

Let us examine the longitudinal oscillations of such a rod. These oscillations

are often, somewhat loosely, referred to as sound waves. It is again convenient to

let

.

Let us examine the longitudinal oscillations of such a rod. These oscillations

are often, somewhat loosely, referred to as sound waves. It is again convenient to

let  denote position along the rod. Thus, in equilibrium, the

two ends of the rod lie at

denote position along the rod. Thus, in equilibrium, the

two ends of the rod lie at  and

and  . Suppose that a longitudinal wave

causes an

. Suppose that a longitudinal wave

causes an  -directed displacement

-directed displacement  of the various elements of the rod from their equilibrium positions. Consider a thin section of the rod, of length

of the various elements of the rod from their equilibrium positions. Consider a thin section of the rod, of length  , lying between

, lying between

and

and

. The displacements of the left and right boundaries

of the section are

. The displacements of the left and right boundaries

of the section are

and

and

, respectively. Thus, the

change in length of the section, due to the action of the wave, is

, respectively. Thus, the

change in length of the section, due to the action of the wave, is

. Now,

strain in an elastic rod is defined as change in length over unperturbed

length (Love 1944). Thus, the strain in the section of the rod under consideration is

. Now,

strain in an elastic rod is defined as change in length over unperturbed

length (Love 1944). Thus, the strain in the section of the rod under consideration is

|

(5.10) |

In the limit

, this becomes

, this becomes

|

(5.11) |

It is assumed that the strain is small compared to unity; that is,

.

Stress,

.

Stress,

, in an elastic rod is defined as the elastic force

per unit cross-sectional area (ibid.). In a conventional elastic material, the relationship

between stress and strain (for relatively small strains) takes the simple form

, in an elastic rod is defined as the elastic force

per unit cross-sectional area (ibid.). In a conventional elastic material, the relationship

between stress and strain (for relatively small strains) takes the simple form

|

(5.12) |

Here,  is a constant, with the dimensions of pressure, that is known as the

Young's modulus (ibid.). If the strain in a given element is positive then the stress acts to lengthen the

element, and vice versa. (Similarly, in the spring-coupled mass

system investigated in the preceding section, the external forces exerted on an

individual spring act to lengthen it when its extension is positive, and vice versa.)

is a constant, with the dimensions of pressure, that is known as the

Young's modulus (ibid.). If the strain in a given element is positive then the stress acts to lengthen the

element, and vice versa. (Similarly, in the spring-coupled mass

system investigated in the preceding section, the external forces exerted on an

individual spring act to lengthen it when its extension is positive, and vice versa.)

Consider the motion of a thin section of the rod lying between

and

and

. If

. If  is the mass density of the rod then the section's mass

is

is the mass density of the rod then the section's mass

is

. The stress acting on the left boundary of the section

is

. The stress acting on the left boundary of the section

is

. Because stress is force per

unit area, the force acting on the left boundary is

. Because stress is force per

unit area, the force acting on the left boundary is

.

This force is directed in the minus

.

This force is directed in the minus  -direction, assuming that the strain is positive (i.e., the force acts to lengthen the section). Likewise, the force acting

on the right boundary of the section is

-direction, assuming that the strain is positive (i.e., the force acts to lengthen the section). Likewise, the force acting

on the right boundary of the section is

, and

is directed in the positive

, and

is directed in the positive  -direction, assuming that the strain is positive (i.e., the force again acts to lengthen the section). Finally, the mean longitudinal (i.e.,

-direction, assuming that the strain is positive (i.e., the force again acts to lengthen the section). Finally, the mean longitudinal (i.e.,  -directed) acceleration of the

section is

-directed) acceleration of the

section is

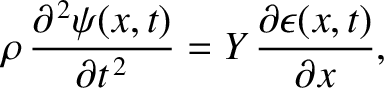

. Hence, the section's longitudinal equation of motion

becomes

. Hence, the section's longitudinal equation of motion

becomes

![$\displaystyle \rho\,A\,\delta x\,\frac{\partial^{\,2}\psi(x,t)}{\partial t^{\,2}} = A\,Y\left[\epsilon(x+\delta x/2,t)-\epsilon(x-\delta x/2,t)\right].$](img1172.png) |

(5.13) |

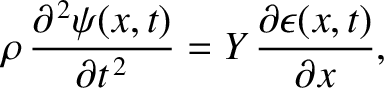

In the limit

, this expression reduces to

, this expression reduces to

|

(5.14) |

or

|

(5.15) |

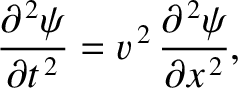

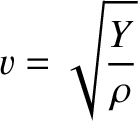

where

|

(5.16) |

is a constant having the dimensions of velocity, which turns

out to be the propagation speed of longitudinal waves along the rod (see Section 6.2), and

use has been made of Equation (5.11). Equation (5.15) has the same mathematical form as Equation (4.30), which

governs the motion of transverse waves on a uniform string. This implies that

longitudinal and transverse waves in continuous dynamical systems (i.e., systems with an infinite number of degrees of freedom) can be described using the same mathematical

equation.

In order to solve Equation (5.15), we need to specify boundary conditions at the

two ends of the rod. Suppose that the left end of the rod is fixed; that is, it

is clamped in place such that it

cannot move. This implies that

. Suppose, on the other hand, that

the left end of the rod is free; that is, it is not attached to anything.

This implies that

. Suppose, on the other hand, that

the left end of the rod is free; that is, it is not attached to anything.

This implies that

, because there is nothing that the end can exert a force (or a stress) on, and vice versa. It follows from Equations (5.11) and (5.12) that

, because there is nothing that the end can exert a force (or a stress) on, and vice versa. It follows from Equations (5.11) and (5.12) that

. Likewise, if the right end of the rod is

fixed then

. Likewise, if the right end of the rod is

fixed then

, and if the right end is free then

, and if the right end is free then

.

.

Suppose, for the sake of argument, that the left end of the rod is free, and the right

end is fixed. It follows that

, and

, and

.

Let us search for normal modes of the form

.

Let us search for normal modes of the form

|

(5.17) |

where  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are constants. The

preceding expression automatically satisfies the boundary condition

are constants. The

preceding expression automatically satisfies the boundary condition

. The other boundary condition is satisfied provided

. The other boundary condition is satisfied provided

|

(5.18) |

which yields

|

(5.19) |

where  is an integer. As usual, the imposition of the boundary conditions leads

to a quantization of the possible mode wavenumbers.

Substitution of Equation (5.17) into the equation of motion, (5.15), yields the normal mode dispersion relation

is an integer. As usual, the imposition of the boundary conditions leads

to a quantization of the possible mode wavenumbers.

Substitution of Equation (5.17) into the equation of motion, (5.15), yields the normal mode dispersion relation

|

(5.20) |

The preceding dispersion relation is consistent with the previously derived dispersion relation (5.9), given that

and

and  . Here,

. Here,  is the interplane spacing,

is the interplane spacing,  the mass of a section

of the rod containing a single plane of atoms, and

the mass of a section

of the rod containing a single plane of atoms, and  the effective force constant

between neighboring atomic planes.

the effective force constant

between neighboring atomic planes.

It follows, from the previous analysis, that the  th longitudinal normal mode of an elastic rod, of length

th longitudinal normal mode of an elastic rod, of length  , whose left end is free, and whose

right end is fixed, is

associated with the characteristic displacement pattern

, whose left end is free, and whose

right end is fixed, is

associated with the characteristic displacement pattern

![$\displaystyle \psi_n(x,t) = A_n\,\cos\left[(n-1/2)\,\pi\,\frac{x}{l}\right]\cos(\omega_n\,t-\phi_n),$](img1186.png) |

(5.21) |

where

|

(5.22) |

Here,  and

and  are constants that are determined by the initial conditions.

It can be demonstrated that only those normal modes whose mode numbers are positive integers yield unique displacement patterns.

Equation (5.21) describes a standing wave whose nodes (i.e., points where

are constants that are determined by the initial conditions.

It can be demonstrated that only those normal modes whose mode numbers are positive integers yield unique displacement patterns.

Equation (5.21) describes a standing wave whose nodes (i.e., points where  for all

for all  ) are evenly spaced

a distance

) are evenly spaced

a distance  apart. The boundary condition

apart. The boundary condition

ensures that the right end of the rod is always coincident with a node.

On the other hand, the boundary condition

ensures that the right end of the rod is always coincident with a node.

On the other hand, the boundary condition

ensures that the left hand of the rod is always coincident with a point of

maximum amplitude oscillation [i.e., a point where

ensures that the left hand of the rod is always coincident with a point of

maximum amplitude oscillation [i.e., a point where

].

Such a point is known as an anti-node. The anti-nodes associated with a given normal mode lie halfway between the corresponding nodes.

According to Equation (5.22), the normal mode oscillation frequencies depend linearly on

mode number. Finally, it can be shown that, in the long wavelength limit

].

Such a point is known as an anti-node. The anti-nodes associated with a given normal mode lie halfway between the corresponding nodes.

According to Equation (5.22), the normal mode oscillation frequencies depend linearly on

mode number. Finally, it can be shown that, in the long wavelength limit  , the normal modes and normal frequencies of a uniform elastic

rod specified in Equations (5.21) and (5.22) are analogous

to the normal modes and normal frequencies of a linear array of identical spring-coupled masses specified in Equations (5.7) and (5.8), and pictured in

Figures 5.2 and 5.3.

, the normal modes and normal frequencies of a uniform elastic

rod specified in Equations (5.21) and (5.22) are analogous

to the normal modes and normal frequencies of a linear array of identical spring-coupled masses specified in Equations (5.7) and (5.8), and pictured in

Figures 5.2 and 5.3.

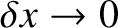

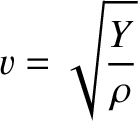

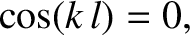

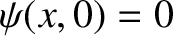

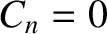

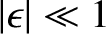

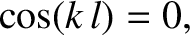

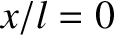

Figure 5.4:

Time evolution of the normalized longitudinal displacement of a thin elastic rod whose left end is free (and is struck with a hammer at  ), and whose right end is fixed. The top-left, top-right, middle-left, middle-right, bottom-left, and bottom-right

panels correspond to

), and whose right end is fixed. The top-left, top-right, middle-left, middle-right, bottom-left, and bottom-right

panels correspond to

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

and

,

and  , respectively.

, respectively.

|

|

Because Equation (5.15) is linear, its most general solution

is a linear combination of all of the normal modes; that is,

![$\displaystyle \psi(x,t) = \sum_{n'=1,\infty} A_{n'}\,\cos\left[(n'-1/2)\,\pi\,\frac{x}{l}\right]\,\cos\left[(n'-1/2)\,\pi\,\frac{v\,t}{l}-\phi_{n'}\right].$](img1192.png) |

(5.23) |

The constants  and

and  are determined from the initial

displacement,

are determined from the initial

displacement,

![$\displaystyle \psi(x,0) = \sum_{n'=1,\infty} A_{n'}\,\cos \phi_{n'}\,\cos\left[(n'-1/2)\,\pi\,\frac{x}{l}\right],$](img1193.png) |

(5.24) |

and the initial velocity,

![$\displaystyle \dot{\psi}(x,0) = \frac{\pi\,v}{l}\sum_{n'=1,\infty} (n'-1/2)\,A_{n'}\,\sin \phi_{n'}\,\cos\left[(n'-1/2)\,\pi\,\frac{x}{l}\right].$](img1194.png) |

(5.25) |

It can be demonstrated that [cf., Equation (4.53)]

![$\displaystyle \frac{2}{l}\int_0^l \cos\left[(n-1/2)\,\pi\,\frac{x}{l}\right]\,\cos\left[(n'-1/2)\,\pi\,\frac{x}{l}\right]dx = \delta_{n,n'}.$](img1195.png) |

(5.26) |

Thus, multiplying Equation (5.24) by

![$(2/l)\,\cos[(n-1/2)\,\pi\,x/l]$](img1196.png) , and integrating in

, and integrating in  from 0 to

from 0 to  , we obtain

, we obtain

![$\displaystyle C_n = \frac{2}{l} \int_0^l\psi(x,0)\,\cos\left[(n-1/2)\,\pi\,\frac{x}{l}\right]dx = A_n\,\cos\phi_n,$](img1197.png) |

(5.27) |

where use has been made of Equations (5.26) and (4.54).

Likewise, Equation (5.25) gives

![$\displaystyle S_n =\frac{2}{v\,(n-1/2)\,\pi} \int_0^l\dot{\psi}(x,0)\,\cos\left[(n-1/2)\,\pi\,\frac{x}{l}\right]dx = A_n\,\sin\phi_n.$](img1198.png) |

(5.28) |

Finally,

and

and

.

.

Suppose, for the sake of example, that the rod is initially at rest, and that its left end is hit with a hammer at

in such a manner that a section of the rod lying between

in such a manner that a section of the rod lying between  and

and  (where

(where  )

acquires an instantaneous velocity

)

acquires an instantaneous velocity  . It follows that

. It follows that

.

Furthermore,

.

Furthermore,

if

if

, and

, and

otherwise.

It can be demonstrated that these initial conditions yield

otherwise.

It can be demonstrated that these initial conditions yield  ,

,

,

,

![$\displaystyle A_n =S_n= \frac{V_0\,a}{v}\,\frac{2}{\pi}\,\frac{\sin[(n-1/2)\,\pi\,a/l]}{(n-1/2)^{\,2}\,\pi\,a/l},$](img1207.png) |

(5.29) |

and

![$\displaystyle \psi(x,t) = \sum_{n=1,\infty} A_n\,\cos\left[(n-1/2)\,\pi\,\frac{x}{l}\right]\sin\left[(n-1/2)\,\pi\,\frac{t}{\tau}\right],$](img1208.png) |

(5.30) |

where  . Figure 5.4 shows the time evolution of the normalized rod

displacement,

. Figure 5.4 shows the time evolution of the normalized rod

displacement,

, calculated from the preceding equations using the first 100 normal modes (i.e.,

, calculated from the preceding equations using the first 100 normal modes (i.e.,  ), and choosing

), and choosing  .

It can be seen that the hammer blow

generates a displacement wave that initially develops at the free end of the rod (

.

It can be seen that the hammer blow

generates a displacement wave that initially develops at the free end of the rod ( ), which is

the end that is struck, propagates along the rod at the velocity

), which is

the end that is struck, propagates along the rod at the velocity  , and reflects off the fixed end (

, and reflects off the fixed end ( ) at time

) at time  with

no phase shift. (The wave front is traveling from the left to the right in all panels except the final one, where it is traveling from right to left.)

with

no phase shift. (The wave front is traveling from the left to the right in all panels except the final one, where it is traveling from right to left.)

and cross-sectional area

and cross-sectional area  .

Let us examine the longitudinal oscillations of such a rod. These oscillations

are often, somewhat loosely, referred to as sound waves. It is again convenient to

let

.

Let us examine the longitudinal oscillations of such a rod. These oscillations

are often, somewhat loosely, referred to as sound waves. It is again convenient to

let  denote position along the rod. Thus, in equilibrium, the

two ends of the rod lie at

denote position along the rod. Thus, in equilibrium, the

two ends of the rod lie at  and

and  . Suppose that a longitudinal wave

causes an

. Suppose that a longitudinal wave

causes an  -directed displacement

-directed displacement  of the various elements of the rod from their equilibrium positions. Consider a thin section of the rod, of length

of the various elements of the rod from their equilibrium positions. Consider a thin section of the rod, of length  , lying between

, lying between

and

and

. The displacements of the left and right boundaries

of the section are

. The displacements of the left and right boundaries

of the section are

and

and

, respectively. Thus, the

change in length of the section, due to the action of the wave, is

, respectively. Thus, the

change in length of the section, due to the action of the wave, is

. Now,

strain in an elastic rod is defined as change in length over unperturbed

length (Love 1944). Thus, the strain in the section of the rod under consideration is

. Now,

strain in an elastic rod is defined as change in length over unperturbed

length (Love 1944). Thus, the strain in the section of the rod under consideration is

, this becomes

It is assumed that the strain is small compared to unity; that is,

, this becomes

It is assumed that the strain is small compared to unity; that is,

.

Stress,

.

Stress,

, in an elastic rod is defined as the elastic force

per unit cross-sectional area (ibid.). In a conventional elastic material, the relationship

between stress and strain (for relatively small strains) takes the simple form

Here,

, in an elastic rod is defined as the elastic force

per unit cross-sectional area (ibid.). In a conventional elastic material, the relationship

between stress and strain (for relatively small strains) takes the simple form

Here,  is a constant, with the dimensions of pressure, that is known as the

Young's modulus (ibid.). If the strain in a given element is positive then the stress acts to lengthen the

element, and vice versa. (Similarly, in the spring-coupled mass

system investigated in the preceding section, the external forces exerted on an

individual spring act to lengthen it when its extension is positive, and vice versa.)

is a constant, with the dimensions of pressure, that is known as the

Young's modulus (ibid.). If the strain in a given element is positive then the stress acts to lengthen the

element, and vice versa. (Similarly, in the spring-coupled mass

system investigated in the preceding section, the external forces exerted on an

individual spring act to lengthen it when its extension is positive, and vice versa.)

and

and

. If

. If  is the mass density of the rod then the section's mass

is

is the mass density of the rod then the section's mass

is

. The stress acting on the left boundary of the section

is

. The stress acting on the left boundary of the section

is

. Because stress is force per

unit area, the force acting on the left boundary is

. Because stress is force per

unit area, the force acting on the left boundary is

.

This force is directed in the minus

.

This force is directed in the minus  -direction, assuming that the strain is positive (i.e., the force acts to lengthen the section). Likewise, the force acting

on the right boundary of the section is

-direction, assuming that the strain is positive (i.e., the force acts to lengthen the section). Likewise, the force acting

on the right boundary of the section is

, and

is directed in the positive

, and

is directed in the positive  -direction, assuming that the strain is positive (i.e., the force again acts to lengthen the section). Finally, the mean longitudinal (i.e.,

-direction, assuming that the strain is positive (i.e., the force again acts to lengthen the section). Finally, the mean longitudinal (i.e.,  -directed) acceleration of the

section is

-directed) acceleration of the

section is

. Hence, the section's longitudinal equation of motion

becomes

. Hence, the section's longitudinal equation of motion

becomes

![$\displaystyle \rho\,A\,\delta x\,\frac{\partial^{\,2}\psi(x,t)}{\partial t^{\,2}} = A\,Y\left[\epsilon(x+\delta x/2,t)-\epsilon(x-\delta x/2,t)\right].$](img1172.png)

, this expression reduces to

, this expression reduces to

. Suppose, on the other hand, that

the left end of the rod is free; that is, it is not attached to anything.

This implies that

. Suppose, on the other hand, that

the left end of the rod is free; that is, it is not attached to anything.

This implies that

, because there is nothing that the end can exert a force (or a stress) on, and vice versa. It follows from Equations (5.11) and (5.12) that

, because there is nothing that the end can exert a force (or a stress) on, and vice versa. It follows from Equations (5.11) and (5.12) that

. Likewise, if the right end of the rod is

fixed then

. Likewise, if the right end of the rod is

fixed then

, and if the right end is free then

, and if the right end is free then

.

.

, and

, and

.

Let us search for normal modes of the form

.

Let us search for normal modes of the form

,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are constants. The

preceding expression automatically satisfies the boundary condition

are constants. The

preceding expression automatically satisfies the boundary condition

. The other boundary condition is satisfied provided

. The other boundary condition is satisfied provided

is an integer. As usual, the imposition of the boundary conditions leads

to a quantization of the possible mode wavenumbers.

Substitution of Equation (5.17) into the equation of motion, (5.15), yields the normal mode dispersion relation

is an integer. As usual, the imposition of the boundary conditions leads

to a quantization of the possible mode wavenumbers.

Substitution of Equation (5.17) into the equation of motion, (5.15), yields the normal mode dispersion relation

and

and  . Here,

. Here,  is the interplane spacing,

is the interplane spacing,  the mass of a section

of the rod containing a single plane of atoms, and

the mass of a section

of the rod containing a single plane of atoms, and  the effective force constant

between neighboring atomic planes.

the effective force constant

between neighboring atomic planes.

th longitudinal normal mode of an elastic rod, of length

th longitudinal normal mode of an elastic rod, of length  , whose left end is free, and whose

right end is fixed, is

associated with the characteristic displacement pattern

, whose left end is free, and whose

right end is fixed, is

associated with the characteristic displacement pattern

and

and  are constants that are determined by the initial conditions.

It can be demonstrated that only those normal modes whose mode numbers are positive integers yield unique displacement patterns.

Equation (5.21) describes a standing wave whose nodes (i.e., points where

are constants that are determined by the initial conditions.

It can be demonstrated that only those normal modes whose mode numbers are positive integers yield unique displacement patterns.

Equation (5.21) describes a standing wave whose nodes (i.e., points where  for all

for all  ) are evenly spaced

a distance

) are evenly spaced

a distance  apart. The boundary condition

apart. The boundary condition

ensures that the right end of the rod is always coincident with a node.

On the other hand, the boundary condition

ensures that the right end of the rod is always coincident with a node.

On the other hand, the boundary condition

ensures that the left hand of the rod is always coincident with a point of

maximum amplitude oscillation [i.e., a point where

ensures that the left hand of the rod is always coincident with a point of

maximum amplitude oscillation [i.e., a point where

].

Such a point is known as an anti-node. The anti-nodes associated with a given normal mode lie halfway between the corresponding nodes.

According to Equation (5.22), the normal mode oscillation frequencies depend linearly on

mode number. Finally, it can be shown that, in the long wavelength limit

].

Such a point is known as an anti-node. The anti-nodes associated with a given normal mode lie halfway between the corresponding nodes.

According to Equation (5.22), the normal mode oscillation frequencies depend linearly on

mode number. Finally, it can be shown that, in the long wavelength limit  , the normal modes and normal frequencies of a uniform elastic

rod specified in Equations (5.21) and (5.22) are analogous

to the normal modes and normal frequencies of a linear array of identical spring-coupled masses specified in Equations (5.7) and (5.8), and pictured in

Figures 5.2 and 5.3.

, the normal modes and normal frequencies of a uniform elastic

rod specified in Equations (5.21) and (5.22) are analogous

to the normal modes and normal frequencies of a linear array of identical spring-coupled masses specified in Equations (5.7) and (5.8), and pictured in

Figures 5.2 and 5.3.

![\includegraphics[width=1\textwidth]{Chapter05/fig5_04.eps}](img1191.png)

![$\displaystyle \psi(x,t) = \sum_{n'=1,\infty} A_{n'}\,\cos\left[(n'-1/2)\,\pi\,\frac{x}{l}\right]\,\cos\left[(n'-1/2)\,\pi\,\frac{v\,t}{l}-\phi_{n'}\right].$](img1192.png)

and

and  are determined from the initial

displacement,

and the initial velocity,

It can be demonstrated that [cf., Equation (4.53)]

Thus, multiplying Equation (5.24) by

are determined from the initial

displacement,

and the initial velocity,

It can be demonstrated that [cf., Equation (4.53)]

Thus, multiplying Equation (5.24) by

![$(2/l)\,\cos[(n-1/2)\,\pi\,x/l]$](img1196.png) , and integrating in

, and integrating in  from 0 to

from 0 to  , we obtain

, we obtain

![$\displaystyle C_n = \frac{2}{l} \int_0^l\psi(x,0)\,\cos\left[(n-1/2)\,\pi\,\frac{x}{l}\right]dx = A_n\,\cos\phi_n,$](img1197.png)

![$\displaystyle S_n =\frac{2}{v\,(n-1/2)\,\pi} \int_0^l\dot{\psi}(x,0)\,\cos\left[(n-1/2)\,\pi\,\frac{x}{l}\right]dx = A_n\,\sin\phi_n.$](img1198.png)

and

and

.

.

in such a manner that a section of the rod lying between

in such a manner that a section of the rod lying between  and

and  (where

(where  )

acquires an instantaneous velocity

)

acquires an instantaneous velocity  . It follows that

. It follows that

.

Furthermore,

.

Furthermore,

if

if

, and

, and

otherwise.

It can be demonstrated that these initial conditions yield

otherwise.

It can be demonstrated that these initial conditions yield  ,

,

,

,

![$\displaystyle A_n =S_n= \frac{V_0\,a}{v}\,\frac{2}{\pi}\,\frac{\sin[(n-1/2)\,\pi\,a/l]}{(n-1/2)^{\,2}\,\pi\,a/l},$](img1207.png)

![$\displaystyle \psi(x,t) = \sum_{n=1,\infty} A_n\,\cos\left[(n-1/2)\,\pi\,\frac{x}{l}\right]\sin\left[(n-1/2)\,\pi\,\frac{t}{\tau}\right],$](img1208.png)

. Figure 5.4 shows the time evolution of the normalized rod

displacement,

. Figure 5.4 shows the time evolution of the normalized rod

displacement,

, calculated from the preceding equations using the first 100 normal modes (i.e.,

, calculated from the preceding equations using the first 100 normal modes (i.e.,  ), and choosing

), and choosing  .

It can be seen that the hammer blow

generates a displacement wave that initially develops at the free end of the rod (

.

It can be seen that the hammer blow

generates a displacement wave that initially develops at the free end of the rod ( ), which is

the end that is struck, propagates along the rod at the velocity

), which is

the end that is struck, propagates along the rod at the velocity  , and reflects off the fixed end (

, and reflects off the fixed end ( ) at time

) at time  with

no phase shift. (The wave front is traveling from the left to the right in all panels except the final one, where it is traveling from right to left.)

with

no phase shift. (The wave front is traveling from the left to the right in all panels except the final one, where it is traveling from right to left.)