Next: Angular momentum of a

Up: Angular momentum

Previous: Angular momentum of a

Consider a rigid object rotating about some fixed axis with angular velocity

.

Let us model this object as a swarm of

.

Let us model this object as a swarm of  particles. Suppose that the

particles. Suppose that the  th particle

has mass

th particle

has mass  , position vector

, position vector  , and velocity

, and velocity  .

Incidentally, it is

assumed that the object's axis of rotation passes through the origin of our

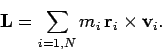

coordinate system. The total angular momentum of the object,

.

Incidentally, it is

assumed that the object's axis of rotation passes through the origin of our

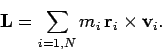

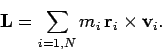

coordinate system. The total angular momentum of the object,  , is simply the

vector sum of the angular momenta of the

, is simply the

vector sum of the angular momenta of the  particles from which it is made up. Hence,

particles from which it is made up. Hence,

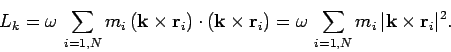

|

(423) |

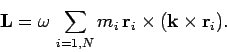

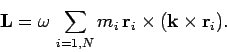

Now, for a rigidly rotating object we can write (see Sect. 8.4)

|

(424) |

Let

|

(425) |

where  is a unit vector pointing along the object's axis of rotation (in the sense

given by the right-hand grip rule).

It follows that

is a unit vector pointing along the object's axis of rotation (in the sense

given by the right-hand grip rule).

It follows that

|

(426) |

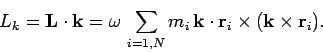

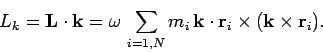

Let us calculate the component of  along the object's rotation axis--i.e.,

the component along the

along the object's rotation axis--i.e.,

the component along the  axis. We can write

axis. We can write

|

(427) |

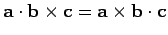

However, since

,

the above expression can be rewritten

,

the above expression can be rewritten

|

(428) |

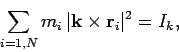

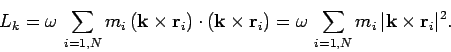

Now,

|

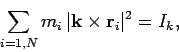

(429) |

where  is the moment of inertia of the object about the

is the moment of inertia of the object about the  axis.

(see Sect. 8.6). Hence, it follows that

axis.

(see Sect. 8.6). Hence, it follows that

|

(430) |

According to the above formula, the component of a rigid body's angular

momentum vector along its axis of rotation is simply the product

of the body's moment of inertia about this axis and the body's angular velocity.

Does this result imply that we can automatically write

|

(431) |

Unfortunately, in general, the answer to the above question is no! This

conclusion follows because the

body may possess non-zero angular momentum components about axes perpendicular to

its axis of rotation. Thus, in general, the angular momentum vector of a rotating body

is not parallel to its angular velocity vector. This is a major difference from

translational motion, where linear momentum is always found to be parallel

to linear velocity.

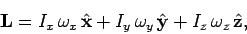

For a rigid object rotating with angular velocity

,

,  ,

,

, we can write the object's angular momentum

, we can write the object's angular momentum

,

,  ,

,

in the form

in the form

where  is the moment of inertia of the object about the

is the moment of inertia of the object about the  -axis, etc. Here, it is

again assumed that the origin of our coordinate system lies on the object's

axis of rotation. Note that the above equations are only valid when the

-axis, etc. Here, it is

again assumed that the origin of our coordinate system lies on the object's

axis of rotation. Note that the above equations are only valid when the  -,

-,  -, and

-, and

-axes are aligned in a certain very special manner--in fact, they must be aligned along the

so-called principal axes of the object (these axes invariably coincide with the object's

main symmetry axes). Note that it is always possible to find three, mutually perpendicular,

principal axes of rotation which pass through a given point in a rigid body.

Reconstructing

-axes are aligned in a certain very special manner--in fact, they must be aligned along the

so-called principal axes of the object (these axes invariably coincide with the object's

main symmetry axes). Note that it is always possible to find three, mutually perpendicular,

principal axes of rotation which pass through a given point in a rigid body.

Reconstructing  from its components, we obtain

from its components, we obtain

|

(435) |

where  is a unit vector pointing along the

is a unit vector pointing along the  -axis, etc.

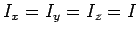

It is clear, from the above equation, that the reason

-axis, etc.

It is clear, from the above equation, that the reason  is not generally parallel

to

is not generally parallel

to

is because the moments of inertia of a rigid object about

its different

possible axes of rotation are not generally the same. In other words, if

is because the moments of inertia of a rigid object about

its different

possible axes of rotation are not generally the same. In other words, if  then

then

, and the angular momentum and angular velocity vectors

are always parallel. However, if

, and the angular momentum and angular velocity vectors

are always parallel. However, if

, which is usually the case,

then

, which is usually the case,

then  is not, in general,

parallel to

is not, in general,

parallel to

.

.

Although Eq. (435) suggests that the angular momentum of a rigid object

is not generally parallel to its angular velocity, this equation also implies that there

are, at least, three special axes of rotation for which this is the case.

Suppose, for instance, that the object rotates about the  -axis, so that

-axis, so that

. It follows from Eq. (435) that

. It follows from Eq. (435) that

|

(436) |

Thus, in this case, the angular momentum vector is parallel to the angular

velocity vector. The same can be said for rotation about the  - or

- or  - axes.

We conclude that when a rigid object rotates about one of its principal axes

then its angular momentum is parallel to its angular velocity, but not, in general,

otherwise.

- axes.

We conclude that when a rigid object rotates about one of its principal axes

then its angular momentum is parallel to its angular velocity, but not, in general,

otherwise.

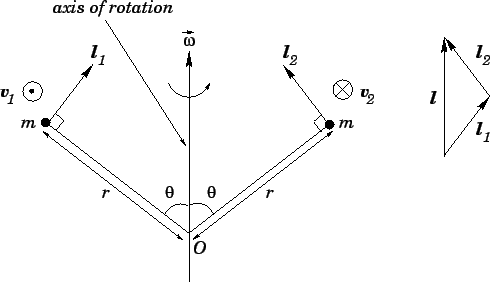

How can we identify a principal axis of a rigid object? At the simplest level,

a principal axis is one about which the object possesses axial symmetry.

The required type of symmetry is illustrated in Fig. 86. Assuming that

the object can be modeled as a swarm of particles--for every

particle of mass  , located a distance

, located a distance  from the origin, and subtending an

angle

from the origin, and subtending an

angle  with the rotation axis, there must be an identical particle located on

diagrammatically the opposite side of the rotation axis. As shown in the diagram,

the angular momentum vectors of such a matched pair of particles can be added together to form

a resultant angular momentum vector which is parallel to the axis of rotation. Thus, if

the object is composed entirely of matched particle pairs then its angular momentum

vector must be parallel to its angular velocity vector. The generalization of this

argument to deal with continuous objects is fairly straightforward. For instance, symmetry implies

that any axis of rotation which passes through the centre of a uniform sphere is

a principal axis of that object. Likewise, a perpendicular axis which passes through the

centre of a uniform disk is a principal axis. Finally, a perpendicular axis which passes

through the centre of a uniform rod is a principal axis.

with the rotation axis, there must be an identical particle located on

diagrammatically the opposite side of the rotation axis. As shown in the diagram,

the angular momentum vectors of such a matched pair of particles can be added together to form

a resultant angular momentum vector which is parallel to the axis of rotation. Thus, if

the object is composed entirely of matched particle pairs then its angular momentum

vector must be parallel to its angular velocity vector. The generalization of this

argument to deal with continuous objects is fairly straightforward. For instance, symmetry implies

that any axis of rotation which passes through the centre of a uniform sphere is

a principal axis of that object. Likewise, a perpendicular axis which passes through the

centre of a uniform disk is a principal axis. Finally, a perpendicular axis which passes

through the centre of a uniform rod is a principal axis.

Figure 86:

A principal axis of rotation.

|

Next: Angular momentum of a

Up: Angular momentum

Previous: Angular momentum of a

Richard Fitzpatrick

2006-02-02

![]() along the object's rotation axis--i.e.,

the component along the

along the object's rotation axis--i.e.,

the component along the ![]() axis. We can write

axis. We can write

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

,

![]() , we can write the object's angular momentum

, we can write the object's angular momentum

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

,

![]() in the form

in the form

![]() -axis, so that

-axis, so that

![]() . It follows from Eq. (435) that

. It follows from Eq. (435) that

![]() , located a distance

, located a distance ![]() from the origin, and subtending an

angle

from the origin, and subtending an

angle ![]() with the rotation axis, there must be an identical particle located on

diagrammatically the opposite side of the rotation axis. As shown in the diagram,

the angular momentum vectors of such a matched pair of particles can be added together to form

a resultant angular momentum vector which is parallel to the axis of rotation. Thus, if

the object is composed entirely of matched particle pairs then its angular momentum

vector must be parallel to its angular velocity vector. The generalization of this

argument to deal with continuous objects is fairly straightforward. For instance, symmetry implies

that any axis of rotation which passes through the centre of a uniform sphere is

a principal axis of that object. Likewise, a perpendicular axis which passes through the

centre of a uniform disk is a principal axis. Finally, a perpendicular axis which passes

through the centre of a uniform rod is a principal axis.

with the rotation axis, there must be an identical particle located on

diagrammatically the opposite side of the rotation axis. As shown in the diagram,

the angular momentum vectors of such a matched pair of particles can be added together to form

a resultant angular momentum vector which is parallel to the axis of rotation. Thus, if

the object is composed entirely of matched particle pairs then its angular momentum

vector must be parallel to its angular velocity vector. The generalization of this

argument to deal with continuous objects is fairly straightforward. For instance, symmetry implies

that any axis of rotation which passes through the centre of a uniform sphere is

a principal axis of that object. Likewise, a perpendicular axis which passes through the

centre of a uniform disk is a principal axis. Finally, a perpendicular axis which passes

through the centre of a uniform rod is a principal axis.