Next: Worked example 9.1: Angular

Up: Angular momentum

Previous: Angular momentum of an

Angular momentum of a multi-component system

Consider a system consisting of  mutually interacting point particles.

Such a system might represent a true multi-component system, such as an asteroid cloud,

or it might represent an extended body.

Let the

mutually interacting point particles.

Such a system might represent a true multi-component system, such as an asteroid cloud,

or it might represent an extended body.

Let the  th particle, whose mass is

th particle, whose mass is  , be located at vector displacement

, be located at vector displacement  .

Suppose that this particle exerts a force

.

Suppose that this particle exerts a force  on the

on the  th particle. By Newton's third

law of motion, the force

th particle. By Newton's third

law of motion, the force  exerted by the

exerted by the  th particle on the

th particle on the  th is

given by

th is

given by

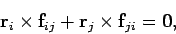

|

(437) |

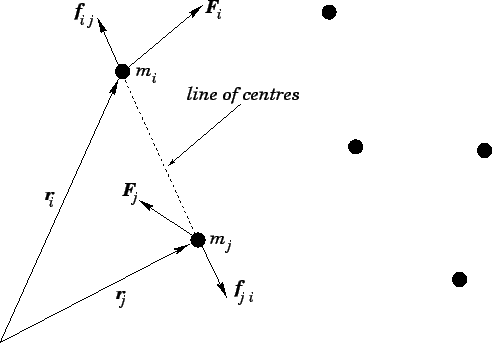

Let us assume that the internal forces acting within the system are central forces--i.e.,

the force  , acting between particles

, acting between particles  and

and  , is directed along the

line of centres of these particles. See Fig. 87.

In other words,

, is directed along the

line of centres of these particles. See Fig. 87.

In other words,

|

(438) |

Incidentally, this is not a particularly restrictive assumption, since most forces occurring in nature are

central forces. For instance, gravity is a central force, electrostatic forces are central,

and the internal stresses acting within a rigid body are approximately central.

Suppose, finally, that the  th particle is subject to an external force

th particle is subject to an external force  .

.

Figure 87:

A multi-component system with central internal forces.

|

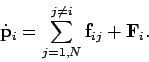

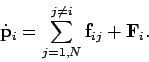

The equation of motion of the  th particle can be written

th particle can be written

|

(439) |

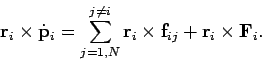

Taking the vector product of this equation with the position vector  , we

obtain

, we

obtain

|

(440) |

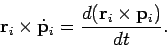

Now, we have already seen that

|

(441) |

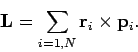

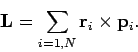

We also know that the total angular momentum,  , of the system (about the origin) can

be written in the form

, of the system (about the origin) can

be written in the form

|

(442) |

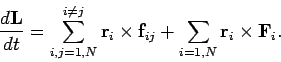

Hence, summing Eq. (440) over all particles, we obtain

|

(443) |

Consider the first expression on the right-hand side of Eq. (443). A general term,

, in this sum can always be paired with a

matching term,

, in this sum can always be paired with a

matching term,

, in which the indices have been swapped.

Making use of Eq. (437), the sum of a general matched pair can be written

, in which the indices have been swapped.

Making use of Eq. (437), the sum of a general matched pair can be written

|

(444) |

However, if the internal forces are central in nature then  is parallel

to

is parallel

to

. Hence, the vector product of these two vectors is zero.

We conclude that

. Hence, the vector product of these two vectors is zero.

We conclude that

|

(445) |

for any values of  and

and  . Thus, the first expression on the right-hand side of Eq. (443)

sums to zero. We are left with

. Thus, the first expression on the right-hand side of Eq. (443)

sums to zero. We are left with

|

(446) |

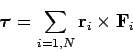

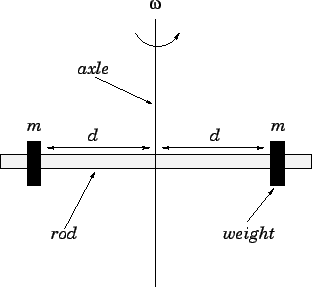

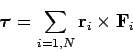

where

|

(447) |

is the net external torque acting on the system (about an axis

passing through the origin). Of course, Eq. (446)

is simply the rotational equation of motion for the system taken as a whole.

Suppose that the system is isolated, such that it is subject to zero net external torque.

It follows from Eq. (446) that, in this case, the total angular momentum of the

system is a conserved quantity. To be more exact, the components of the

total angular momentum taken about any three independent axes are individually conserved quantities.

Conservation of angular momentum is an extremely useful concept which greatly simplifies the

analysis of a wide range of rotating systems. Let us consider some

examples.

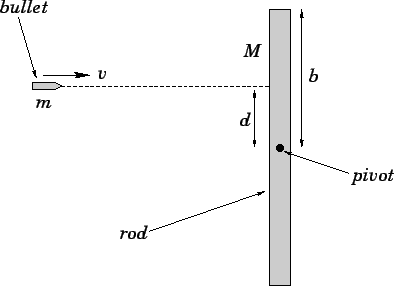

Figure 88:

Two movable weights on a rotating rod.

|

Suppose that two identical weights of mass  are attached to a light rigid rod which

rotates without friction about a perpendicular axis passing through its mid-point. Imagine that

the two weights are equipped with small motors which allow them to travel along the

rod: the motors are synchronized in such a manner that the distance of the two

weights from the axis of rotation is always the same. Let us call this common distance

are attached to a light rigid rod which

rotates without friction about a perpendicular axis passing through its mid-point. Imagine that

the two weights are equipped with small motors which allow them to travel along the

rod: the motors are synchronized in such a manner that the distance of the two

weights from the axis of rotation is always the same. Let us call this common distance

, and let

, and let  be the angular velocity of the rod. See Fig. 88. How

does the angular velocity

be the angular velocity of the rod. See Fig. 88. How

does the angular velocity  change as the distance

change as the distance  is varied?

is varied?

Note that there are no external torques acting on the system. It follows that the

system's angular momentum must remain constant as the weights move along the rod.

Neglecting the contribution of the rod, the moment of inertia of the system is

written

|

(448) |

Since the system is rotating about a principal axis, its angular momentum takes the form

|

(449) |

If  is a constant of the motion then we obtain

is a constant of the motion then we obtain

|

(450) |

In other words, the

system spins faster as the weights move inwards

towards the axis of rotation, and vice versa.

This effect is familiar from figure skating. When a skater spins about a vertical axis,

her angular momentum is approximately a conserved quantity, since the ice

exerts very little torque on her. Thus, if the skater starts spinning with

outstretched arms, and then draws her arms inwards, then her rate of rotation

will spontaneously increase in order to conserve angular momentum. The skater can

slow her rate of rotation by simply pushing her arms outwards again.

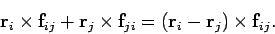

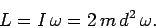

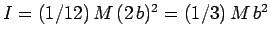

Suppose that a bullet of mass  and velocity

and velocity  strikes, and becomes

embedded in, a stationary rod of mass

strikes, and becomes

embedded in, a stationary rod of mass  and length

and length  which

pivots about a frictionless perpendicular axle passing through its mid-point.

Let the bullet strike the rod normally a distance

which

pivots about a frictionless perpendicular axle passing through its mid-point.

Let the bullet strike the rod normally a distance  from its

axis of rotation. See Fig. 89. What is the instantaneous angular

velocity

from its

axis of rotation. See Fig. 89. What is the instantaneous angular

velocity  of the rod (and bullet) immediately after the collision?

of the rod (and bullet) immediately after the collision?

Figure 89:

A bullet strikes a pivoted rod.

|

Taking the bullet and the rod as a whole, this is again a system upon which no

external torque acts. Thus, we expect the system's net angular momentum to

be the same before and after the collision. Before the collision, only the

bullet possesses angular momentum, since the rod is at rest. As is easily demonstrated, the

bullet's angular momentum about the pivot point is

|

(451) |

i.e., the product of its mass, its velocity, and its distance of closest approach

to the point about which the angular momentum is measured--this is a general result

(for a point particle). After the collision, the bullet lodges a distance  from the pivot, and is forced to co-rotate with the

rod. Hence, the angular momentum of the bullet after the collision is given by

from the pivot, and is forced to co-rotate with the

rod. Hence, the angular momentum of the bullet after the collision is given by

|

(452) |

where  is the angular velocity of the rod. The angular momentum of the

rod after the collision is

is the angular velocity of the rod. The angular momentum of the

rod after the collision is

|

(453) |

where

is the rod's moment of inertia (about a perpendicular

axis passing through its mid-point). Conservation of angular

momentum yields

is the rod's moment of inertia (about a perpendicular

axis passing through its mid-point). Conservation of angular

momentum yields

|

(454) |

or

|

(455) |

Next: Worked example 9.1: Angular

Up: Angular momentum

Previous: Angular momentum of an

Richard Fitzpatrick

2006-02-02

![]() th particle can be written

th particle can be written

![]() , in this sum can always be paired with a

matching term,

, in this sum can always be paired with a

matching term,

![]() , in which the indices have been swapped.

Making use of Eq. (437), the sum of a general matched pair can be written

, in which the indices have been swapped.

Making use of Eq. (437), the sum of a general matched pair can be written

![]() are attached to a light rigid rod which

rotates without friction about a perpendicular axis passing through its mid-point. Imagine that

the two weights are equipped with small motors which allow them to travel along the

rod: the motors are synchronized in such a manner that the distance of the two

weights from the axis of rotation is always the same. Let us call this common distance

are attached to a light rigid rod which

rotates without friction about a perpendicular axis passing through its mid-point. Imagine that

the two weights are equipped with small motors which allow them to travel along the

rod: the motors are synchronized in such a manner that the distance of the two

weights from the axis of rotation is always the same. Let us call this common distance

![]() , and let

, and let ![]() be the angular velocity of the rod. See Fig. 88. How

does the angular velocity

be the angular velocity of the rod. See Fig. 88. How

does the angular velocity ![]() change as the distance

change as the distance ![]() is varied?

is varied?

![]() and velocity

and velocity ![]() strikes, and becomes

embedded in, a stationary rod of mass

strikes, and becomes

embedded in, a stationary rod of mass ![]() and length

and length ![]() which

pivots about a frictionless perpendicular axle passing through its mid-point.

Let the bullet strike the rod normally a distance

which

pivots about a frictionless perpendicular axle passing through its mid-point.

Let the bullet strike the rod normally a distance ![]() from its

axis of rotation. See Fig. 89. What is the instantaneous angular

velocity

from its

axis of rotation. See Fig. 89. What is the instantaneous angular

velocity ![]() of the rod (and bullet) immediately after the collision?

of the rod (and bullet) immediately after the collision?