Fresnel Relations

The theory described in the previous section is sufficient to determine the directions of the reflected and refracted waves, when a

light wave is obliquely incident on a plane interface between two dielectric media. However, it cannot determine

the fractions of the incident energy that are reflected and refracted, respectively. In order to calculate the coefficients of reflection and transmission, it is necessary to take into account both the

electric and the magnetic components of the various waves. It turns out that there are two independent wave polarizations that behave

slightly differently. The first of these is such that the magnetic components of the incident, reflected, and refracted waves are all

parallel to the interface. The second is such that the electric components of these waves are all parallel to the interface.

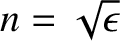

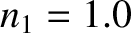

Consider the first polarization. Let the interface correspond to the plane  , let the region

, let the region  be occupied by material of refractive index

be occupied by material of refractive index  , and let

the region

, and let

the region  be occupied by material of refractive index

be occupied by material of refractive index  . Suppose that the incident, reflected, and refracted waves are plane waves, of

angular frequency

. Suppose that the incident, reflected, and refracted waves are plane waves, of

angular frequency  , whose wavevectors lie in the

, whose wavevectors lie in the  -

- plane. See Figure 7.7. The equations governing oblique electromagnetic wave propagation through a uniform dielectric medium are a generalization of Equations (6.135)–(6.136), and take the form

(see Appendix C)

plane. See Figure 7.7. The equations governing oblique electromagnetic wave propagation through a uniform dielectric medium are a generalization of Equations (6.135)–(6.136), and take the form

(see Appendix C)

where

|

(7.53) |

is the electric displacement,  the characteristic wave speed, and

the characteristic wave speed, and

the refractive index. Suppose that, as described in the previous section,

in the region

the refractive index. Suppose that, as described in the previous section,

in the region  , and

, and

|

(7.54) |

in the region  . Here,

. Here,

is the vacuum wavenumber,

is the vacuum wavenumber,  the angle of incidence, and

the angle of incidence, and  the angle of

refraction. See Figure 7.7. In writing the previous expressions, we have made use of the

law of reflection (i.e.,

the angle of

refraction. See Figure 7.7. In writing the previous expressions, we have made use of the

law of reflection (i.e.,

), as well as the law of refraction (i.e.,

), as well as the law of refraction (i.e.,

).

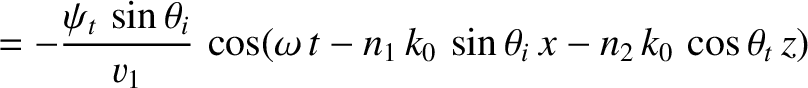

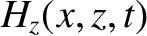

The two terms on the right-hand side of Equation (7.54) correspond to the incident and reflected waves,

respectively. The term on the right-hand side of Equation (7.55) corresponds to the refracted wave.

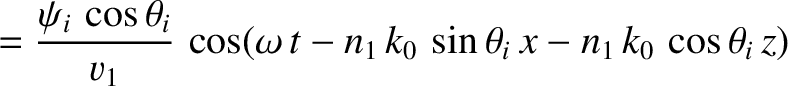

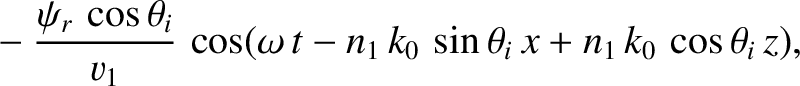

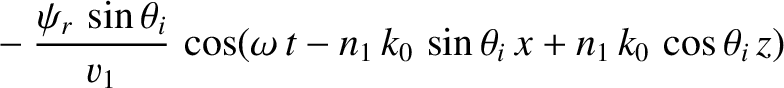

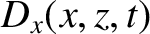

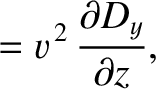

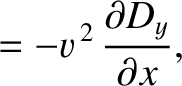

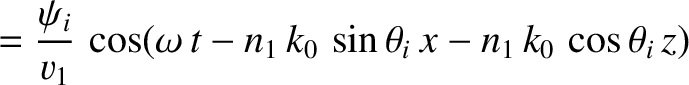

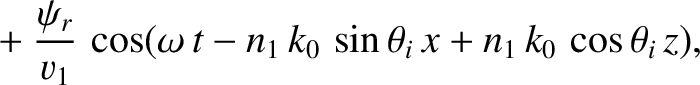

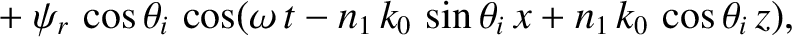

Substitution of Equations (7.54)–(7.55) into the governing differential equations, (7.50)–(7.52), yields

in the region

).

The two terms on the right-hand side of Equation (7.54) correspond to the incident and reflected waves,

respectively. The term on the right-hand side of Equation (7.55) corresponds to the refracted wave.

Substitution of Equations (7.54)–(7.55) into the governing differential equations, (7.50)–(7.52), yields

in the region  , and

in the region

, and

in the region  .

.

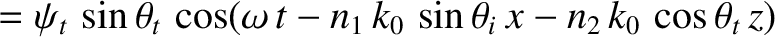

According to standard electromagnetic theory (see Appendix C), both the normal and the tangential components of the magnetic

intensity must be continuous at the interface. This implies that

![$\displaystyle [H_y]_{z=0_-}^{z=0_+}=0,$](img1979.png) |

(7.59) |

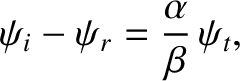

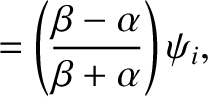

which yields

|

(7.60) |

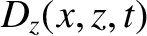

Standard electromagnetic theory (ibid.) also implies that the normal component of the electric displacement, as well as the tangential

component of the electric field, are continuous at the interface. In other words,

![$\displaystyle [D_z]_{z=0_-}^{z=0^+} = 0,$](img1981.png) |

(7.61) |

and

![$\displaystyle [E_x]_{z=0_-}^{z=0_+}=\left[\frac{D_x}{\epsilon\,\epsilon_0}\right]_{z=0_-}^{z=0_+} = 0.$](img1982.png) |

(7.62) |

The former of these conditions again gives Equation (7.61), whereas the latter yields

|

(7.63) |

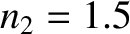

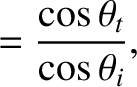

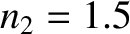

where

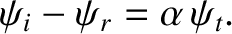

It follows that

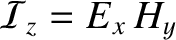

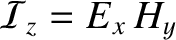

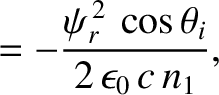

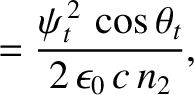

The electromagnetic energy flux in the  -direction (i.e., normal to the interface) is (see Appendix C),

-direction (i.e., normal to the interface) is (see Appendix C),

|

(7.68) |

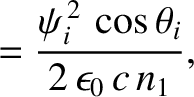

[cf. Equation (6.127)]. Thus, the mean energy fluxes associated with the incident, reflected, and refracted

waves are

respectively.

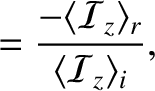

The coefficients of reflection and transmission are defined

respectively.

Hence, it follows that

These expressions are known as Fresnel relations, and are the generalizations of expressions (6.151) and (6.152)

for the case of oblique incidence (with the polarization in which the magnetic field is parallel to the interface).

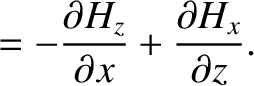

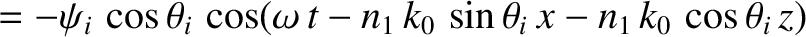

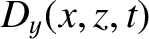

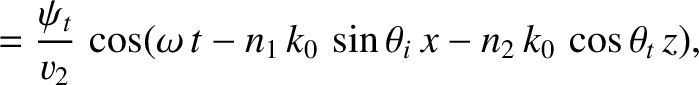

Let us now consider the second polarization, in which the electric components of the incident, reflected, and

refracted waves are all parallel to the interface. In this case, the governing equations are (see Appendix C)

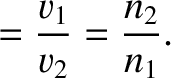

If we make the transformations

,

,

,

,

,

,

then we can reuse the solutions that we derived for the other polarization.

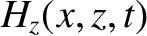

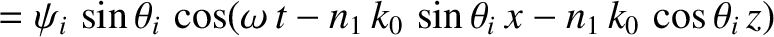

We find that

in the region

then we can reuse the solutions that we derived for the other polarization.

We find that

in the region  , and

in the region

, and

in the region  . The first two matching conditions at the interface are that the normal and tangential components of the

magnetic intensity are continuous. (See Appendix C.) In other words,

The first of these conditions yields

. The first two matching conditions at the interface are that the normal and tangential components of the

magnetic intensity are continuous. (See Appendix C.) In other words,

The first of these conditions yields

|

(7.87) |

whereas the second

gives

|

(7.88) |

The final matching condition at the interface is that the tangential component of the electric field is continuous. (See Appendix C.) In other words,

![$\displaystyle [E_y]_{z=0_-}^{z=0_+} = \left[\frac{D_y}{\epsilon\,\epsilon_0}\right]_{z=0_-}^{z=0_+}=0,$](img2026.png) |

(7.89) |

which again yields Equation (7.88).

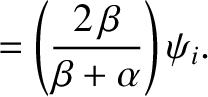

It follows that

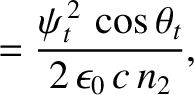

The electromagnetic energy flux in the  -direction is (see Appendix C),

-direction is (see Appendix C),

|

(7.92) |

Thus, the mean energy fluxes associated with the incident, reflected, and refracted

waves are

respectively.

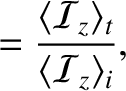

Hence, the coefficients of reflection and transmission are

respectively.

These expressions are the Fresnel relations

for the polarization in which the electric field is parallel to the interface.

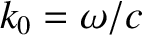

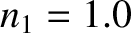

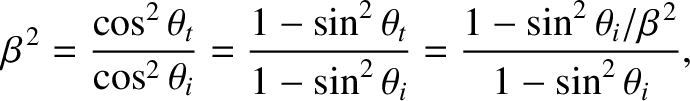

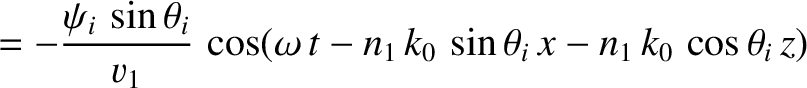

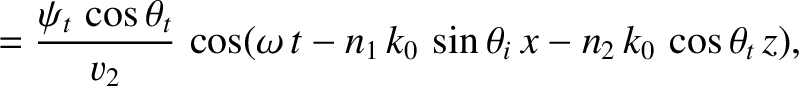

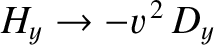

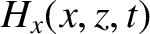

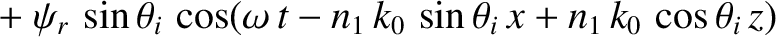

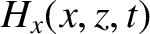

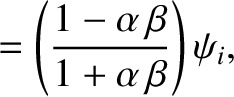

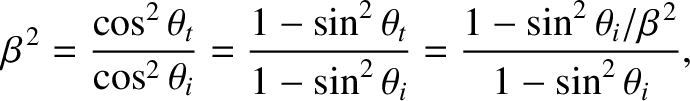

Figure 7.8:

Coefficients of reflection (solid curves) and transmission (dashed curves) for oblique incidence from air ( ) to

glass (

) to

glass ( ). The left-hand panel shows the wave polarization

for which the magnetic field is parallel to the interface, whereas the

right-hand panel shows the wave polarization for which the

electric field is parallel to the interface. The Brewster angle is

). The left-hand panel shows the wave polarization

for which the magnetic field is parallel to the interface, whereas the

right-hand panel shows the wave polarization for which the

electric field is parallel to the interface. The Brewster angle is

.

.

|

|

It can be seen that, at oblique incidence, the Fresnel relations (7.75) and

(7.76) for the polarization in which the magnetic

field is parallel to the interface are different to the corresponding relations

(7.97) and (7.98) for the polarization

in which the electric field is parallel to the interface. This implies that

the coefficients of reflection and transmission for these two polarizations

are, in general, different.

Figure 7.8 shows the coefficients of reflection and transmission

for oblique incidence from air ( ) to

glass (

) to

glass ( ). In general, it can

be seen that the coefficient of reflection rises, and the coefficient of

transmission falls, as the angle of incidence increases. However,

for the polarization in which the magnetic field is parallel to the interface, there is a particular angle of incidence,

known as the Brewster angle,

at which the reflected intensity is zero. There is no similar behavior for

the polarization in which the electric field is parallel to the interface.

). In general, it can

be seen that the coefficient of reflection rises, and the coefficient of

transmission falls, as the angle of incidence increases. However,

for the polarization in which the magnetic field is parallel to the interface, there is a particular angle of incidence,

known as the Brewster angle,

at which the reflected intensity is zero. There is no similar behavior for

the polarization in which the electric field is parallel to the interface.

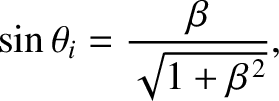

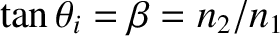

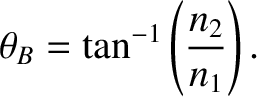

It follows from Equation (7.75) that the Brewster angle corresponds

to the condition

|

(7.98) |

or

|

(7.99) |

where use has been made of Snell's law. The previous expression

reduces to

|

(7.100) |

or

. Hence, the Brewster angle corresponds to

. Hence, the Brewster angle corresponds to

, where

, where

|

(7.101) |

If unpolarized light is incident on an air/glass (say) interface at the Brewster angle

then the reflected light is  linearly polarized. (See Section 7.7.)

linearly polarized. (See Section 7.7.)

The fact that the coefficient of reflection for the polarization in which the electric field is parallel to the interface is generally

greater than that for the other polarization (see Figure 7.8) implies that sunlight reflected from a horizontal water or snow surface is partially linearly polarized, with the horizontal polarization predominating over the vertical one. Such reflected light may be so intense as to cause glare. Polaroid sunglasses help reduce this glare by blocking horizontally polarized light.

, let the region

, let the region  be occupied by material of refractive index

be occupied by material of refractive index  , and let

the region

, and let

the region  be occupied by material of refractive index

be occupied by material of refractive index  . Suppose that the incident, reflected, and refracted waves are plane waves, of

angular frequency

. Suppose that the incident, reflected, and refracted waves are plane waves, of

angular frequency  , whose wavevectors lie in the

, whose wavevectors lie in the  -

- plane. See Figure 7.7. The equations governing oblique electromagnetic wave propagation through a uniform dielectric medium are a generalization of Equations (6.135)–(6.136), and take the form

(see Appendix C)

plane. See Figure 7.7. The equations governing oblique electromagnetic wave propagation through a uniform dielectric medium are a generalization of Equations (6.135)–(6.136), and take the form

(see Appendix C)

the characteristic wave speed, and

the characteristic wave speed, and

the refractive index. Suppose that, as described in the previous section,

in the region

the refractive index. Suppose that, as described in the previous section,

in the region  , and

in the region

, and

in the region  . Here,

. Here,

is the vacuum wavenumber,

is the vacuum wavenumber,  the angle of incidence, and

the angle of incidence, and  the angle of

refraction. See Figure 7.7. In writing the previous expressions, we have made use of the

law of reflection (i.e.,

the angle of

refraction. See Figure 7.7. In writing the previous expressions, we have made use of the

law of reflection (i.e.,

), as well as the law of refraction (i.e.,

), as well as the law of refraction (i.e.,

).

The two terms on the right-hand side of Equation (7.54) correspond to the incident and reflected waves,

respectively. The term on the right-hand side of Equation (7.55) corresponds to the refracted wave.

Substitution of Equations (7.54)–(7.55) into the governing differential equations, (7.50)–(7.52), yields

).

The two terms on the right-hand side of Equation (7.54) correspond to the incident and reflected waves,

respectively. The term on the right-hand side of Equation (7.55) corresponds to the refracted wave.

Substitution of Equations (7.54)–(7.55) into the governing differential equations, (7.50)–(7.52), yields

, and

, and

.

.

-direction (i.e., normal to the interface) is (see Appendix C),

-direction (i.e., normal to the interface) is (see Appendix C),

,

,

,

,

,

,

then we can reuse the solutions that we derived for the other polarization.

We find that

then we can reuse the solutions that we derived for the other polarization.

We find that

, and

, and

. The first two matching conditions at the interface are that the normal and tangential components of the

magnetic intensity are continuous. (See Appendix C.) In other words,

The first of these conditions yields

whereas the second

gives

. The first two matching conditions at the interface are that the normal and tangential components of the

magnetic intensity are continuous. (See Appendix C.) In other words,

The first of these conditions yields

whereas the second

gives

-direction is (see Appendix C),

-direction is (see Appendix C),

![\includegraphics[width=1\textwidth]{Chapter07/fig7_08.eps}](img2032.png)

) to

glass (

) to

glass ( ). In general, it can

be seen that the coefficient of reflection rises, and the coefficient of

transmission falls, as the angle of incidence increases. However,

for the polarization in which the magnetic field is parallel to the interface, there is a particular angle of incidence,

known as the Brewster angle,

at which the reflected intensity is zero. There is no similar behavior for

the polarization in which the electric field is parallel to the interface.

). In general, it can

be seen that the coefficient of reflection rises, and the coefficient of

transmission falls, as the angle of incidence increases. However,

for the polarization in which the magnetic field is parallel to the interface, there is a particular angle of incidence,

known as the Brewster angle,

at which the reflected intensity is zero. There is no similar behavior for

the polarization in which the electric field is parallel to the interface.

. Hence, the Brewster angle corresponds to

. Hence, the Brewster angle corresponds to

, where

, where

linearly polarized. (See Section 7.7.)

linearly polarized. (See Section 7.7.)