Next: Mean values

Up: Applications of statistical thermodynamics

Previous: Boltzmann distributions

The simplest microscopic system which we can analyze using the Boltzmann distribution

is one

which has only two possible states (there would clearly be little point in analyzing

a system with only one possible state). Most elements, and some compounds, are

paramagnetic: i.e., their constituent atoms, or molecules,

possess a permanent

magnetic moment due to the presence of one or more unpaired electrons. Consider a

substance whose constituent

particles contain only one unpaired electron. Such particles have spin

, and consequently possess an intrinsic magnetic moment

, and consequently possess an intrinsic magnetic moment  .

According to quantum mechanics, the magnetic moment of a spin

.

According to quantum mechanics, the magnetic moment of a spin  particle

can

point either parallel or antiparallel to an external magnetic field

particle

can

point either parallel or antiparallel to an external magnetic field  .

Let us determine the mean magnetic moment

.

Let us determine the mean magnetic moment

(in the direction

of

(in the direction

of  ) of the constituent particles of

the substance when its absolute temperature is

) of the constituent particles of

the substance when its absolute temperature is  .

We assume, for the sake of simplicity, that each atom (or molecule)

only interacts weakly

with its neighbouring atoms. This enables us to focus attention on a single atom, and

treat the remaining atoms as a heat bath at temperature

.

We assume, for the sake of simplicity, that each atom (or molecule)

only interacts weakly

with its neighbouring atoms. This enables us to focus attention on a single atom, and

treat the remaining atoms as a heat bath at temperature  .

.

Our atom can be in one of two possible states: the  state in which its spin

points up (i.e., parallel to

state in which its spin

points up (i.e., parallel to  ), and the

), and the  state in which its

spin points down (i.e., antiparallel to

state in which its

spin points down (i.e., antiparallel to  ). In the

). In the  state,

the atomic magnetic moment is parallel to the magnetic field, so that

state,

the atomic magnetic moment is parallel to the magnetic field, so that

. The magnetic energy of the atom is

. The magnetic energy of the atom is

.

In the

.

In the  state, the atomic magnetic moment is antiparallel to the magnetic

field, so that

state, the atomic magnetic moment is antiparallel to the magnetic

field, so that  . The magnetic energy of the atom is

. The magnetic energy of the atom is

.

.

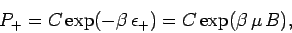

According to the Boltzmann distribution, the probability of finding the atom

in the  state is

state is

|

(381) |

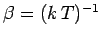

where  is a constant, and

is a constant, and

.

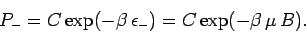

Likewise, the probability of finding the atom in the

.

Likewise, the probability of finding the atom in the  state is

state is

|

(382) |

Clearly, the most probable

state is the state with the lowest energy [i.e., the  state].

Thus, the mean magnetic moment points in the direction of the magnetic field

(i.e., the atom is more likely to point parallel to the field than antiparallel).

state].

Thus, the mean magnetic moment points in the direction of the magnetic field

(i.e., the atom is more likely to point parallel to the field than antiparallel).

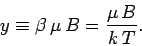

It is clear that the critical parameter in a paramagnetic system is

|

(383) |

This parameter measures the ratio of the typical magnetic energy of the atom to

its typical thermal energy. If the thermal energy greatly exceeds the magnetic

energy then  , and the probability that the atomic moment points parallel

to the magnetic field is about the same as the probability that it points

antiparallel. In this situation, we expect the mean atomic moment to

be small, so that

, and the probability that the atomic moment points parallel

to the magnetic field is about the same as the probability that it points

antiparallel. In this situation, we expect the mean atomic moment to

be small, so that

. On the other hand, if the

magnetic energy greatly exceeds the thermal energy then

. On the other hand, if the

magnetic energy greatly exceeds the thermal energy then  , and the atomic

moment is far more likely to point parallel to the magnetic field than antiparallel.

In this situation, we expect

, and the atomic

moment is far more likely to point parallel to the magnetic field than antiparallel.

In this situation, we expect

.

.

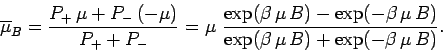

Let us calculate the mean atomic moment

. The usual

definition of a mean value gives

. The usual

definition of a mean value gives

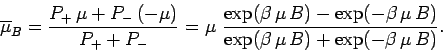

|

(384) |

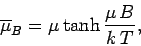

This can also be written

|

(385) |

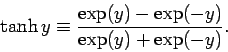

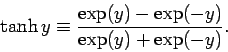

where the hyperbolic tangent is defined

|

(386) |

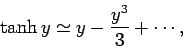

For small arguments,  ,

,

|

(387) |

whereas for large arguments,  ,

,

|

(388) |

It follows that at comparatively high temperatures,

,

,

|

(389) |

whereas at comparatively low temperatures,

,

,

|

(390) |

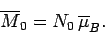

Suppose that the substance contains  atoms (or molecules) per unit volume.

The magnetization is defined as the mean magnetic moment per unit

volume, and is given by

atoms (or molecules) per unit volume.

The magnetization is defined as the mean magnetic moment per unit

volume, and is given by

|

(391) |

At high temperatures,

, the mean magnetic moment, and, hence, the

magnetization, is proportional to the applied magnetic field, so we can write

, the mean magnetic moment, and, hence, the

magnetization, is proportional to the applied magnetic field, so we can write

|

(392) |

where  is a constant of proportionality known as the

magnetic susceptibility.

It is clear that the magnetic susceptibility of a spin 1/2 paramagnetic substance

takes the form

is a constant of proportionality known as the

magnetic susceptibility.

It is clear that the magnetic susceptibility of a spin 1/2 paramagnetic substance

takes the form

|

(393) |

The fact that

is known as Curie's law, because it

was discovered experimentally by Pierre Curie at the end of the nineteenth century.

At low temperatures,

is known as Curie's law, because it

was discovered experimentally by Pierre Curie at the end of the nineteenth century.

At low temperatures,

,

,

|

(394) |

so the magnetization becomes independent of the applied field. This corresponds to

the maximum possible magnetization, where all atomic moments are lined up

parallel to the field. The breakdown of the

law

at low temperatures (or high magnetic fields) is known as saturation.

law

at low temperatures (or high magnetic fields) is known as saturation.

Figure 2:

The magnetization (vertical axis) versus  (horizontal axis) curves

for (I) chromium potassium alum (

(horizontal axis) curves

for (I) chromium potassium alum ( ), (II) iron ammonium alum (

), (II) iron ammonium alum ( ), and

(III) gadolinium sulphate (

), and

(III) gadolinium sulphate ( ). The solid lines are the theoretical predictions

whereas

the data points are experimental measurements. From W.E. Henry, Phys. Rev. 88, 561 (1952).

). The solid lines are the theoretical predictions

whereas

the data points are experimental measurements. From W.E. Henry, Phys. Rev. 88, 561 (1952).

|

The above analysis is only valid for paramagnetic substances made up of

spin one-half ( ) atoms or molecules. However,

the analysis can easily be generalized

to take account of substances whose constituent particles possess higher spin

(i.e.,

) atoms or molecules. However,

the analysis can easily be generalized

to take account of substances whose constituent particles possess higher spin

(i.e.,  ). Figure 2 compares

the experimental and theoretical magnetization versus

field-strength curves for three different substances made up of spin

). Figure 2 compares

the experimental and theoretical magnetization versus

field-strength curves for three different substances made up of spin  , spin

, spin  ,

and spin

,

and spin  particles, showing the excellent agreement between the two sets of

curves. Note that, in all cases, the magnetization is proportional to the

magnetic field-strength at small field-strengths, but saturates at some

constant value as the field-strength increases.

particles, showing the excellent agreement between the two sets of

curves. Note that, in all cases, the magnetization is proportional to the

magnetic field-strength at small field-strengths, but saturates at some

constant value as the field-strength increases.

The previous analysis completely neglects any interaction between the

spins of neighbouring atoms or molecules. It turns out that this is

a fairly good approximation for paramagnetic substances. However, for

ferromagnetic substances, in which the spins of neighbouring atoms

interact very strongly, this approximation breaks down completely. Thus, the

above analysis does not apply to ferromagnetic substances.

Next: Mean values

Up: Applications of statistical thermodynamics

Previous: Boltzmann distributions

Richard Fitzpatrick

2006-02-02

![]() state in which its spin

points up (i.e., parallel to

state in which its spin

points up (i.e., parallel to ![]() ), and the

), and the ![]() state in which its

spin points down (i.e., antiparallel to

state in which its

spin points down (i.e., antiparallel to ![]() ). In the

). In the ![]() state,

the atomic magnetic moment is parallel to the magnetic field, so that

state,

the atomic magnetic moment is parallel to the magnetic field, so that

![]() . The magnetic energy of the atom is

. The magnetic energy of the atom is

![]() .

In the

.

In the ![]() state, the atomic magnetic moment is antiparallel to the magnetic

field, so that

state, the atomic magnetic moment is antiparallel to the magnetic

field, so that ![]() . The magnetic energy of the atom is

. The magnetic energy of the atom is

![]() .

.

![]() state is

state is

![]() . The usual

definition of a mean value gives

. The usual

definition of a mean value gives

![]() atoms (or molecules) per unit volume.

The magnetization is defined as the mean magnetic moment per unit

volume, and is given by

atoms (or molecules) per unit volume.

The magnetization is defined as the mean magnetic moment per unit

volume, and is given by

![]() ) atoms or molecules. However,

the analysis can easily be generalized

to take account of substances whose constituent particles possess higher spin

(i.e.,

) atoms or molecules. However,

the analysis can easily be generalized

to take account of substances whose constituent particles possess higher spin

(i.e., ![]() ). Figure 2 compares

the experimental and theoretical magnetization versus

field-strength curves for three different substances made up of spin

). Figure 2 compares

the experimental and theoretical magnetization versus

field-strength curves for three different substances made up of spin ![]() , spin

, spin ![]() ,

and spin

,

and spin ![]() particles, showing the excellent agreement between the two sets of

curves. Note that, in all cases, the magnetization is proportional to the

magnetic field-strength at small field-strengths, but saturates at some

constant value as the field-strength increases.

particles, showing the excellent agreement between the two sets of

curves. Note that, in all cases, the magnetization is proportional to the

magnetic field-strength at small field-strengths, but saturates at some

constant value as the field-strength increases.