Next: Paramagnetism

Up: Applications of statistical thermodynamics

Previous: Introduction

Boltzmann distributions

We have gained some understanding of the macroscopic properties of the

air around us. For instance, we know

something about its internal energy and specific heat capacity.

How can we obtain some information about the

statistical properties of the molecules which make

up air? Consider a specific molecule: it constantly collides with

its immediate neighbour molecules,

and occasionally bounces off the walls of the room. These

interactions ``inform'' it about the macroscopic state of the air,

such as its temperature, pressure, and volume. The

statistical distribution of the molecule over its own particular microstates must

be consistent with this macrostate. In other words, if we have a large group

of such molecules with similar statistical distributions,

then they must be equivalent to

air with the appropriate macroscopic properties. So, it ought to be possible

to calculate the probability distribution of the molecule over its microstates

from a knowledge of these macroscopic properties.

We can think of the interaction of a molecule with the

air in a classroom as

analogous to the interaction of a small system  in thermal contact with a

heat reservoir

in thermal contact with a

heat reservoir  . The air acts like a heat reservoir because its energy

fluctuations due to any interactions

with the molecule are far too small to affect any

of its macroscopic parameters. Let us

determine the probability

. The air acts like a heat reservoir because its energy

fluctuations due to any interactions

with the molecule are far too small to affect any

of its macroscopic parameters. Let us

determine the probability  of finding system

of finding system  in one particular

microstate

in one particular

microstate  of energy

of energy  when it is thermal equilibrium with the heat

reservoir

when it is thermal equilibrium with the heat

reservoir  .

.

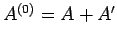

As usual, we assume fairly weak interaction between  and

and  , so that

the energies of these two systems

are additive. The energy of

, so that

the energies of these two systems

are additive. The energy of  is not known at this

stage. In fact, only the total energy of the combined system

is not known at this

stage. In fact, only the total energy of the combined system

is known. Suppose that the

total energy lies in the range

is known. Suppose that the

total energy lies in the range  to

to

.

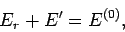

The overall energy is constant in time, since

.

The overall energy is constant in time, since  is assumed to be an isolated system, so

is assumed to be an isolated system, so

|

(369) |

where  denotes the energy of the reservoir

denotes the energy of the reservoir  . Let

. Let

be the

number of microstates accessible to the reservoir when its energy lies in the

range

be the

number of microstates accessible to the reservoir when its energy lies in the

range  to

to  . Clearly, if system

. Clearly, if system  has an energy

has an energy  then

the reservoir

then

the reservoir  must have an energy close to

must have an energy close to

. Hence,

since

. Hence,

since  is in one definite state (i.e., state

is in one definite state (i.e., state  ), and the total

number of states accessible to

), and the total

number of states accessible to  is

is

, it

follows that

the total number

of states accessible to the combined system is simply

, it

follows that

the total number

of states accessible to the combined system is simply

.

The principle of equal a priori probabilities tells us the the probability

of occurrence of a particular situation is proportional to the number

of accessible microstates. Thus,

.

The principle of equal a priori probabilities tells us the the probability

of occurrence of a particular situation is proportional to the number

of accessible microstates. Thus,

|

(370) |

where  is a constant of proportionality which is independent of

is a constant of proportionality which is independent of  .

This constant can be determined by the normalization condition

.

This constant can be determined by the normalization condition

|

(371) |

where the sum is over all possible states of system  , irrespective of their energy.

, irrespective of their energy.

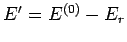

Let us now make use of the fact that system  is far smaller than system

is far smaller than system  .

It follows that

.

It follows that

, so the slowly varying logarithm of

, so the slowly varying logarithm of  can be Taylor expanded about

can be Taylor expanded about  . Thus,

. Thus,

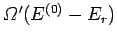

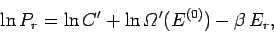

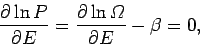

![\begin{displaymath}

\ln P_r = \ln C' +\ln {\mit\Omega}'(E^{(0)}) -\left[\frac{\partial \ln {\mit\Omega}'}

{\partial E'} \right]_0 E_r +\cdots.

\end{displaymath}](img927.png) |

(372) |

Note that we must expand  , rather than

, rather than  itself, because the latter

function varies so rapidly with energy

that the radius of convergence of its Taylor series

is far too small for the series to be of any practical use.

The higher order terms in Eq. (372) can be safely

neglected, because

itself, because the latter

function varies so rapidly with energy

that the radius of convergence of its Taylor series

is far too small for the series to be of any practical use.

The higher order terms in Eq. (372) can be safely

neglected, because

. Now the derivative

. Now the derivative

![\begin{displaymath}

\left[\frac{\partial \ln {\mit\Omega}'}{\partial E'} \right]_0 \equiv \beta

\end{displaymath}](img928.png) |

(373) |

is evaluated at the fixed energy  , and is, thus, a constant independent

of the energy

, and is, thus, a constant independent

of the energy  of

of  . In fact, we know, from Sect. 5, that this derivative

is just the

temperature parameter

. In fact, we know, from Sect. 5, that this derivative

is just the

temperature parameter

characterizing the heat

reservoir

characterizing the heat

reservoir  . Hence, Eq. (372) becomes

. Hence, Eq. (372) becomes

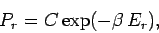

|

(374) |

giving

|

(375) |

where  is a constant independent of

is a constant independent of  . The parameter

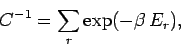

. The parameter  is determined by

the normalization condition, which gives

is determined by

the normalization condition, which gives

|

(376) |

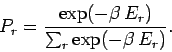

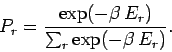

so that the distribution becomes

|

(377) |

This is known as the Boltzmann probability distribution, and is undoubtably

the most famous result in statistical physics.

The Boltzmann distribution often causes confusion. People who are used to the

principle of equal a priori probabilities, which says that all microstates

are equally probable, are understandably surprised when they come across the

Boltzmann distribution which says that high energy microstates are markedly less

probable then low energy states. However, there is no need for any

confusion. The principle of equal a priori probabilities applies to

the whole system, whereas the Boltzmann distribution only applies to

a small part of the system. The two results are perfectly consistent.

If the small system is in a microstate with a comparatively high energy  then

the rest of the system (i.e., the reservoir) has a slightly lower energy

then

the rest of the system (i.e., the reservoir) has a slightly lower energy  than

usual (since the overall energy is fixed). The number of accessible microstates

of the reservoir is a very strongly increasing function of its energy. It

follows that when the small system has a

high energy then significantly less states

than usual are accessible to the reservoir, and so the number of microstates

accessible

to the overall system is reduced, and, hence, the configuration is comparatively

unlikely. The strong increase in the number of accessible microstates of the

reservoir with increasing

than

usual (since the overall energy is fixed). The number of accessible microstates

of the reservoir is a very strongly increasing function of its energy. It

follows that when the small system has a

high energy then significantly less states

than usual are accessible to the reservoir, and so the number of microstates

accessible

to the overall system is reduced, and, hence, the configuration is comparatively

unlikely. The strong increase in the number of accessible microstates of the

reservoir with increasing  gives rise to the strong (i.e., exponential) decrease

in the likelihood of a state

gives rise to the strong (i.e., exponential) decrease

in the likelihood of a state  of the small system with increasing

of the small system with increasing  .

The exponential factor

.

The exponential factor

is called the Boltzmann factor.

is called the Boltzmann factor.

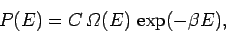

The Boltzmann distribution gives the probability of finding the small system  in one particular state

in one particular state  of energy

of energy  . The probability

. The probability

that

that  has an energy in the small range between

has an energy in the small range between  and

and  is just the sum of all the probabilities of the states which lie in this

range. However, since each of these states has approximately the same Boltzmann

factor this sum can be written

is just the sum of all the probabilities of the states which lie in this

range. However, since each of these states has approximately the same Boltzmann

factor this sum can be written

|

(378) |

where

is the number of microstates of

is the number of microstates of  whose energies lie

in the appropriate

range. Suppose that system

whose energies lie

in the appropriate

range. Suppose that system  is itself a large system, but still very

much smaller than system

is itself a large system, but still very

much smaller than system  . For a large system, we expect

. For a large system, we expect

to

be a very rapidly increasing function of energy, so the probability

to

be a very rapidly increasing function of energy, so the probability  is the product of a rapidly increasing function of

is the product of a rapidly increasing function of  and another

rapidly decreasing

function (i.e., the Boltzmann factor). This gives a sharp

maximum of

and another

rapidly decreasing

function (i.e., the Boltzmann factor). This gives a sharp

maximum of  at some particular value of the energy. The larger system

at some particular value of the energy. The larger system  ,

the sharper this maximum becomes. Eventually, the maximum becomes so sharp

that the energy of system

,

the sharper this maximum becomes. Eventually, the maximum becomes so sharp

that the energy of system  is almost bound to lie at the most probable energy.

As usual, the most probable energy is evaluated by looking for the maximum of

is almost bound to lie at the most probable energy.

As usual, the most probable energy is evaluated by looking for the maximum of

, so

, so

|

(379) |

giving

|

(380) |

Of course, this corresponds to the situation in which the temperature

of  is the same as that of the reservoir. This is a result which we

have seen before (see Sect. 5). Note, however, that the Boltzmann

distribution is applicable no matter how small system

is the same as that of the reservoir. This is a result which we

have seen before (see Sect. 5). Note, however, that the Boltzmann

distribution is applicable no matter how small system  is, so

it is a far more

general result than any we have previously obtained.

is, so

it is a far more

general result than any we have previously obtained.

Next: Paramagnetism

Up: Applications of statistical thermodynamics

Previous: Introduction

Richard Fitzpatrick

2006-02-02

![]() in thermal contact with a

heat reservoir

in thermal contact with a

heat reservoir ![]() . The air acts like a heat reservoir because its energy

fluctuations due to any interactions

with the molecule are far too small to affect any

of its macroscopic parameters. Let us

determine the probability

. The air acts like a heat reservoir because its energy

fluctuations due to any interactions

with the molecule are far too small to affect any

of its macroscopic parameters. Let us

determine the probability ![]() of finding system

of finding system ![]() in one particular

microstate

in one particular

microstate ![]() of energy

of energy ![]() when it is thermal equilibrium with the heat

reservoir

when it is thermal equilibrium with the heat

reservoir ![]() .

.

![]() and

and ![]() , so that

the energies of these two systems

are additive. The energy of

, so that

the energies of these two systems

are additive. The energy of ![]() is not known at this

stage. In fact, only the total energy of the combined system

is not known at this

stage. In fact, only the total energy of the combined system

![]() is known. Suppose that the

total energy lies in the range

is known. Suppose that the

total energy lies in the range ![]() to

to

![]() .

The overall energy is constant in time, since

.

The overall energy is constant in time, since ![]() is assumed to be an isolated system, so

is assumed to be an isolated system, so

![]() is far smaller than system

is far smaller than system ![]() .

It follows that

.

It follows that

![]() , so the slowly varying logarithm of

, so the slowly varying logarithm of ![]() can be Taylor expanded about

can be Taylor expanded about ![]() . Thus,

. Thus,

![\begin{displaymath}

\left[\frac{\partial \ln {\mit\Omega}'}{\partial E'} \right]_0 \equiv \beta

\end{displaymath}](img928.png)

![]() then

the rest of the system (i.e., the reservoir) has a slightly lower energy

then

the rest of the system (i.e., the reservoir) has a slightly lower energy ![]() than

usual (since the overall energy is fixed). The number of accessible microstates

of the reservoir is a very strongly increasing function of its energy. It

follows that when the small system has a

high energy then significantly less states

than usual are accessible to the reservoir, and so the number of microstates

accessible

to the overall system is reduced, and, hence, the configuration is comparatively

unlikely. The strong increase in the number of accessible microstates of the

reservoir with increasing

than

usual (since the overall energy is fixed). The number of accessible microstates

of the reservoir is a very strongly increasing function of its energy. It

follows that when the small system has a

high energy then significantly less states

than usual are accessible to the reservoir, and so the number of microstates

accessible

to the overall system is reduced, and, hence, the configuration is comparatively

unlikely. The strong increase in the number of accessible microstates of the

reservoir with increasing ![]() gives rise to the strong (i.e., exponential) decrease

in the likelihood of a state

gives rise to the strong (i.e., exponential) decrease

in the likelihood of a state ![]() of the small system with increasing

of the small system with increasing ![]() .

The exponential factor

.

The exponential factor

![]() is called the Boltzmann factor.

is called the Boltzmann factor.

![]() in one particular state

in one particular state ![]() of energy

of energy ![]() . The probability

. The probability

![]() that

that ![]() has an energy in the small range between

has an energy in the small range between ![]() and

and ![]() is just the sum of all the probabilities of the states which lie in this

range. However, since each of these states has approximately the same Boltzmann

factor this sum can be written

is just the sum of all the probabilities of the states which lie in this

range. However, since each of these states has approximately the same Boltzmann

factor this sum can be written