Next: Hydrostatic equilibrium of the

Up: Classical thermodynamics

Previous: Calculation of specific heats

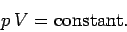

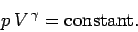

Suppose that the temperature of an ideal

gas is held constant by keeping the gas in thermal

contact with a heat reservoir. If the gas is allowed to expand quasi-statically

under these so called isothermal conditions then the ideal equation of state

tells us that

|

(311) |

This is usually called the isothermal gas law.

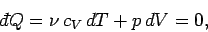

Suppose, now, that the gas is thermally isolated from its surroundings. If

the gas is allowed to expand quasi-statically under these so called

adiabatic

conditions then

it does work on its environment, and, hence, its internal energy is reduced,

and its temperature changes. Let us work out the relationship between the

pressure and volume of the gas during adiabatic expansion.

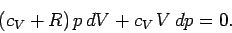

According to the first law of thermodynamics,

|

(312) |

in an adiabatic process (in which no heat is absorbed). The ideal gas

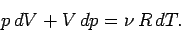

equation

of state can be differentiated, yielding

|

(313) |

The temperature increment  can be eliminated between the above two expressions

to give

can be eliminated between the above two expressions

to give

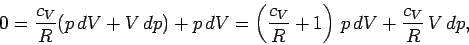

|

(314) |

which reduces to

|

(315) |

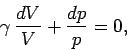

Dividing through by  yields

yields

|

(316) |

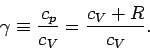

where

|

(317) |

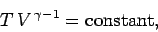

It turns out that  is a very slowly varying function of temperature in most

gases. So, it is always a fairly good approximation to treat the ratio

of specific heats

is a very slowly varying function of temperature in most

gases. So, it is always a fairly good approximation to treat the ratio

of specific heats  as a constant, at least over a limited temperature

range. If

as a constant, at least over a limited temperature

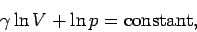

range. If  is constant then we can integrate Eq. (316) to give

is constant then we can integrate Eq. (316) to give

|

(318) |

or

|

(319) |

This is the famous adiabatic gas law.

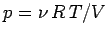

It is very easy to obtain similar relationships between  and

and  and

and  and

and  during adiabatic expansion or contraction. Since

during adiabatic expansion or contraction. Since

, the above formula

also implies that

, the above formula

also implies that

|

(320) |

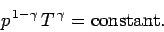

and

|

(321) |

Equations (319)-(321) are all completely equivalent.

Next: Hydrostatic equilibrium of the

Up: Classical thermodynamics

Previous: Calculation of specific heats

Richard Fitzpatrick

2006-02-02