Next: Ferromagnetism

Up: Applications of Statistical Thermodynamics

Previous: Maxwell Velocity Distribution

Effusion

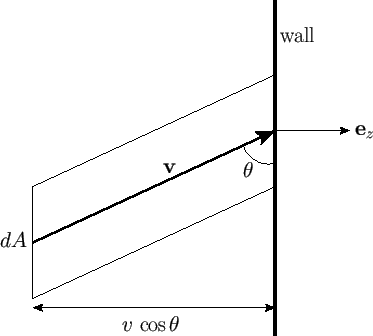

Consider a dilute gas enclosed in a container. Let us calculate how many molecules per unit time strike a unit area of

the container wall.

Consider a wall element of area  . The

. The  -axis is oriented so as to point along the outward

normal of this element. Let

-axis is oriented so as to point along the outward

normal of this element. Let  represent a molecular velocity.

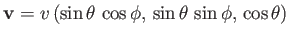

The Cartesian components of this velocity are conveniently written

represent a molecular velocity.

The Cartesian components of this velocity are conveniently written

,

where the standard spherical angles

,

where the standard spherical angles  and

and  specify the velocity vector's direction.

Let us concentrate on those molecules, in the immediate vicinity of the wall element, whose velocities

are such that they lie between

specify the velocity vector's direction.

Let us concentrate on those molecules, in the immediate vicinity of the wall element, whose velocities

are such that they lie between  and

and

. In other words, the velocities are

such that their magnitudes lies between

. In other words, the velocities are

such that their magnitudes lies between  and

and  , their polar angles lie between

, their polar angles lie between

and

and

, and their azimuthal angles lie between

, and their azimuthal angles lie between  and

and

. Molecules of this type

suffer a displacement

. Molecules of this type

suffer a displacement

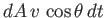

in the infinitesimal time interval

in the infinitesimal time interval  .

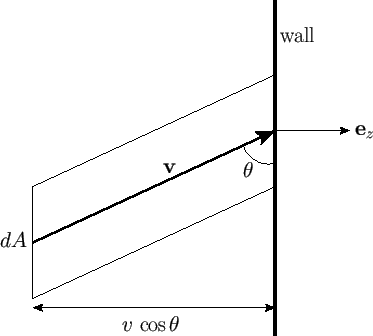

Hence, all molecules that lie within the infinitesimal cylinder of cross-sectional

area

.

Hence, all molecules that lie within the infinitesimal cylinder of cross-sectional

area  , and length

, and length

(whose axis subtends an angle

(whose axis subtends an angle  with the

with the  -axis, and whose two ends are parallel to the wall element),

will strike the wall element within the time interval

-axis, and whose two ends are parallel to the wall element),

will strike the wall element within the time interval  , whereas those

molecules outside this cylinder will not. (See Figure 7.8.) The volume of the cylinder is

, whereas those

molecules outside this cylinder will not. (See Figure 7.8.) The volume of the cylinder is

, whereas the

number of molecules per unit volume in the prescribed velocity range is

, whereas the

number of molecules per unit volume in the prescribed velocity range is

.

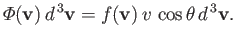

Hence, the number of molecules of this type that

strike the area

.

Hence, the number of molecules of this type that

strike the area  in the time interval

in the time interval  is

is

![$ [f({\bf v}) d^{ 3}{\bf v}] (dA v \cos\theta dt)$](img1756.png) .

Dividing this expression by the area

.

Dividing this expression by the area  , and the time interval

, and the time interval  , we obtain

, we obtain

,

which is defined as the number of molecules, with velocities in the range

,

which is defined as the number of molecules, with velocities in the range  to

to

, that

strike a unit area of the wall per unit time. Thus,

, that

strike a unit area of the wall per unit time. Thus,

|

(7.233) |

Figure:

All molecules with velocity  that lie within the cylinder strike the wall in a unit time interval.

that lie within the cylinder strike the wall in a unit time interval.

|

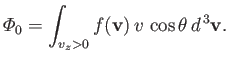

Let

be the total number of molecules that strike a unit area of the wall per unit time.

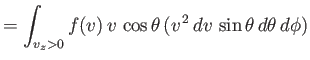

This quantity is simply obtained by summing (7.233) over all possible molecular velocities that would cause molecules to collide with the element of area. This means that we

have to sum over all possible speeds,

be the total number of molecules that strike a unit area of the wall per unit time.

This quantity is simply obtained by summing (7.233) over all possible molecular velocities that would cause molecules to collide with the element of area. This means that we

have to sum over all possible speeds,

, all possible azimuthal angles,

, all possible azimuthal angles,

, and

all polar angles in the range

, and

all polar angles in the range

. (Those molecules with polar angles in the range

. (Those molecules with polar angles in the range

have their velocity

directed away from the wall, and will, hence, not collide with it.) In other words, we have to

sum over all possible velocities,

have their velocity

directed away from the wall, and will, hence, not collide with it.) In other words, we have to

sum over all possible velocities,  , subject to the restriction that the velocity component

, subject to the restriction that the velocity component

is positive. Thus, we have

is positive. Thus, we have

|

(7.234) |

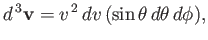

The element of volume in velocity space can be expressed in spherical coordinates:

|

(7.235) |

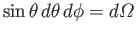

where

is just an element of solid angle.

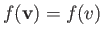

Moreover, in thermal equilibrium,

is just an element of solid angle.

Moreover, in thermal equilibrium,

is only a function of

is only a function of  .

Hence, Equation (7.234) becomes

.

Hence, Equation (7.234) becomes

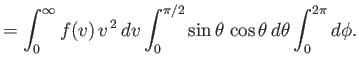

The integral over  gives

gives  , whereas that over

, whereas that over  reduces to

reduces to  . It follows that

. It follows that

|

(7.237) |

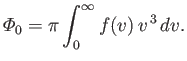

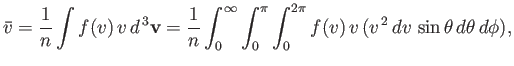

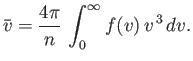

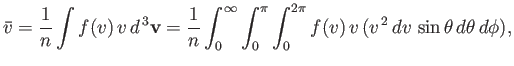

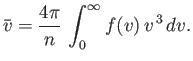

Now, the mean molecular speed is written

|

(7.238) |

which reduces to

|

(7.239) |

Hence, we deduce from Equation (7.237) that

|

(7.240) |

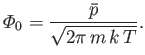

The previous result can be combined with Equation (7.227), and the ideal equation of state,

, to give

, to give

|

(7.241) |

If a sufficiently small hole is made in the wall of the container then the equilibrium of the gas inside the container is

disturbed to a negligible extent. [In practice, a sufficiently small hole is one that is small compared to the molecular mean-free-path (i.e., the

mean distance travelled between collisions) inside the container.] In this case, the number of molecules that emerge through the small hole is the same as

the number of molecules that would strike the area occupied by the hole if the latter were closed off. The process

by which molecules emerge through a small hole is called effusion. The number

of molecules that have speeds in the range between  and

and  , and which emerge through a small hole

of area

, and which emerge through a small hole

of area  , into the solid angle range

, into the solid angle range

, in the forward direction

, in the forward direction  , is given by

, is given by

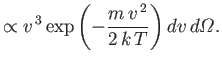

Now, it is difficult to directly verify the Maxwell velocity distribution. However, this

distribution can be verified indirectly by measuring the velocity distribution

of atoms effusing from a small hole in an oven. As we have just seen, the predicted velocity distribution of

the escaping atoms varies like

, in contrast

to the

, in contrast

to the

variation of the velocity distribution

inside the oven. There is good agreement between the experimentally measured velocity distribution of

effusing atoms and the theoretical prediction.

variation of the velocity distribution

inside the oven. There is good agreement between the experimentally measured velocity distribution of

effusing atoms and the theoretical prediction.

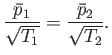

As another example, consider a container that is divided into two parts by a partition containing a small hole.

The container is filled with gas, but one part of the container is maintained at the temperature  , and the other

at the temperature

, and the other

at the temperature  . Let us calculate the relationship between the mean gas pressures,

. Let us calculate the relationship between the mean gas pressures,  and

and  ,

respectively, in the two parts, when the system is in equilibrium. (That is, when a situation is reached in which

neither

,

respectively, in the two parts, when the system is in equilibrium. (That is, when a situation is reached in which

neither  or

or  , nor the amount of gas in either parts, changes with time.) If the hole is

larger than the molecular mean-free-path then the relationship is simply

, nor the amount of gas in either parts, changes with time.) If the hole is

larger than the molecular mean-free-path then the relationship is simply

--otherwise, the

pressure difference would give rise to bulk motion of the gas from one side of the container to the other,

until the pressures were equalized. But, if the dimensions of the hole are less than the mean-free-path then we are

dealing with effusion through the hole, rather than hydrodynamical flow. In this case, the equilibrium

condition requires that the mass of gas on each side remain constant. In other words, the effusion rates in

both directions must be equal. Thus, it follows from Equation (7.241) that

--otherwise, the

pressure difference would give rise to bulk motion of the gas from one side of the container to the other,

until the pressures were equalized. But, if the dimensions of the hole are less than the mean-free-path then we are

dealing with effusion through the hole, rather than hydrodynamical flow. In this case, the equilibrium

condition requires that the mass of gas on each side remain constant. In other words, the effusion rates in

both directions must be equal. Thus, it follows from Equation (7.241) that

|

(7.243) |

Thus, the pressures are not equal. Instead, a higher pressure prevails in the part of the container held at a higher temperature.

Next: Ferromagnetism

Up: Applications of Statistical Thermodynamics

Previous: Maxwell Velocity Distribution

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-25

![]() . The

. The ![]() -axis is oriented so as to point along the outward

normal of this element. Let

-axis is oriented so as to point along the outward

normal of this element. Let ![]() represent a molecular velocity.

The Cartesian components of this velocity are conveniently written

represent a molecular velocity.

The Cartesian components of this velocity are conveniently written

![]() ,

where the standard spherical angles

,

where the standard spherical angles ![]() and

and ![]() specify the velocity vector's direction.

Let us concentrate on those molecules, in the immediate vicinity of the wall element, whose velocities

are such that they lie between

specify the velocity vector's direction.

Let us concentrate on those molecules, in the immediate vicinity of the wall element, whose velocities

are such that they lie between ![]() and

and

![]() . In other words, the velocities are

such that their magnitudes lies between

. In other words, the velocities are

such that their magnitudes lies between ![]() and

and ![]() , their polar angles lie between

, their polar angles lie between

![]() and

and

![]() , and their azimuthal angles lie between

, and their azimuthal angles lie between ![]() and

and

![]() . Molecules of this type

suffer a displacement

. Molecules of this type

suffer a displacement

![]() in the infinitesimal time interval

in the infinitesimal time interval ![]() .

Hence, all molecules that lie within the infinitesimal cylinder of cross-sectional

area

.

Hence, all molecules that lie within the infinitesimal cylinder of cross-sectional

area ![]() , and length

, and length

![]() (whose axis subtends an angle

(whose axis subtends an angle ![]() with the

with the ![]() -axis, and whose two ends are parallel to the wall element),

will strike the wall element within the time interval

-axis, and whose two ends are parallel to the wall element),

will strike the wall element within the time interval ![]() , whereas those

molecules outside this cylinder will not. (See Figure 7.8.) The volume of the cylinder is

, whereas those

molecules outside this cylinder will not. (See Figure 7.8.) The volume of the cylinder is

![]() , whereas the

number of molecules per unit volume in the prescribed velocity range is

, whereas the

number of molecules per unit volume in the prescribed velocity range is

![]() .

Hence, the number of molecules of this type that

strike the area

.

Hence, the number of molecules of this type that

strike the area ![]() in the time interval

in the time interval ![]() is

is

![]() .

Dividing this expression by the area

.

Dividing this expression by the area ![]() , and the time interval

, and the time interval ![]() , we obtain

, we obtain

![]() ,

which is defined as the number of molecules, with velocities in the range

,

which is defined as the number of molecules, with velocities in the range ![]() to

to

![]() , that

strike a unit area of the wall per unit time. Thus,

, that

strike a unit area of the wall per unit time. Thus,

![]() be the total number of molecules that strike a unit area of the wall per unit time.

This quantity is simply obtained by summing (7.233) over all possible molecular velocities that would cause molecules to collide with the element of area. This means that we

have to sum over all possible speeds,

be the total number of molecules that strike a unit area of the wall per unit time.

This quantity is simply obtained by summing (7.233) over all possible molecular velocities that would cause molecules to collide with the element of area. This means that we

have to sum over all possible speeds,

![]() , all possible azimuthal angles,

, all possible azimuthal angles,

![]() , and

all polar angles in the range

, and

all polar angles in the range

![]() . (Those molecules with polar angles in the range

. (Those molecules with polar angles in the range

![]() have their velocity

directed away from the wall, and will, hence, not collide with it.) In other words, we have to

sum over all possible velocities,

have their velocity

directed away from the wall, and will, hence, not collide with it.) In other words, we have to

sum over all possible velocities, ![]() , subject to the restriction that the velocity component

, subject to the restriction that the velocity component

![]() is positive. Thus, we have

is positive. Thus, we have

![]() and

and ![]() , and which emerge through a small hole

of area

, and which emerge through a small hole

of area ![]() , into the solid angle range

, into the solid angle range

![]() , in the forward direction

, in the forward direction ![]() , is given by

, is given by

![]() , and the other

at the temperature

, and the other

at the temperature ![]() . Let us calculate the relationship between the mean gas pressures,

. Let us calculate the relationship between the mean gas pressures, ![]() and

and ![]() ,

respectively, in the two parts, when the system is in equilibrium. (That is, when a situation is reached in which

neither

,

respectively, in the two parts, when the system is in equilibrium. (That is, when a situation is reached in which

neither ![]() or

or ![]() , nor the amount of gas in either parts, changes with time.) If the hole is

larger than the molecular mean-free-path then the relationship is simply

, nor the amount of gas in either parts, changes with time.) If the hole is

larger than the molecular mean-free-path then the relationship is simply

![]() --otherwise, the

pressure difference would give rise to bulk motion of the gas from one side of the container to the other,

until the pressures were equalized. But, if the dimensions of the hole are less than the mean-free-path then we are

dealing with effusion through the hole, rather than hydrodynamical flow. In this case, the equilibrium

condition requires that the mass of gas on each side remain constant. In other words, the effusion rates in

both directions must be equal. Thus, it follows from Equation (7.241) that

--otherwise, the

pressure difference would give rise to bulk motion of the gas from one side of the container to the other,

until the pressures were equalized. But, if the dimensions of the hole are less than the mean-free-path then we are

dealing with effusion through the hole, rather than hydrodynamical flow. In this case, the equilibrium

condition requires that the mass of gas on each side remain constant. In other words, the effusion rates in

both directions must be equal. Thus, it follows from Equation (7.241) that