Next: Calculation of Specific Heats

Up: Classical Thermodynamics

Previous: Ideal Gas Equation of

Suppose that a body absorbs an amount of heat

,

and its temperature consequently rises by

,

and its temperature consequently rises by

. The usual definition

of the heat capacity, or specific heat, of the body is

. The usual definition

of the heat capacity, or specific heat, of the body is

|

(6.26) |

If the body consists of  moles of some substance then the molar

specific heat (i.e., the specific heat of one mole of this substance) is

defined

moles of some substance then the molar

specific heat (i.e., the specific heat of one mole of this substance) is

defined

|

(6.27) |

In writing the previous expressions, we have tacitly assumed that the specific heat

of a body is independent of its temperature. In general, this is not true. We

can overcome this problem by only allowing the body in question to absorb a very

small amount of heat, so that its temperature only rises slightly, and its

specific heat remains approximately constant. In the limit that the amount of

absorbed heat becomes infinitesimal, we obtain

|

(6.28) |

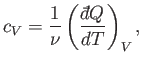

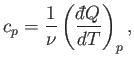

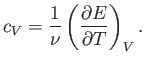

In classical thermodynamics, it is usual to define two molar specific heats. Firstly,

the molar specific heat at constant volume, denoted

|

(6.29) |

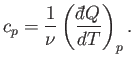

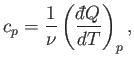

and, secondly, the molar specific heat at constant pressure, denoted

|

(6.30) |

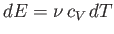

Consider the molar specific heat at constant volume of an ideal gas.

Because  , no work is done by

the gas on its surroundings,

and the first law of thermodynamics reduces to

, no work is done by

the gas on its surroundings,

and the first law of thermodynamics reduces to

|

(6.31) |

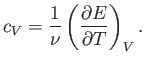

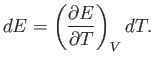

It follows from Equation (6.29) that

|

(6.32) |

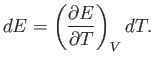

Now, for an ideal gas, the internal energy is volume independent. [See Equation (6.25).]

Thus, the previous expression implies that the specific heat at constant volume is also

volume independent. Because  is a function of

is a function of  only, we can write

only, we can write

|

(6.33) |

The previous two expressions can be combined to give

|

(6.34) |

for an ideal gas.

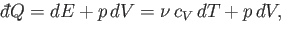

Let us now consider the molar specific heat at constant pressure of an ideal

gas. In general, if the

pressure is kept constant then the volume changes, and so the gas does work on its

environment. According to the first law of thermodynamics,

|

(6.35) |

where use has been made of Equation (6.34).

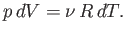

The equation of state of an ideal gas, (6.10), implies that if the

volume changes by  , the temperature changes by

, the temperature changes by  , and the pressure

remains constant, then

, and the pressure

remains constant, then

|

(6.36) |

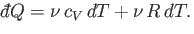

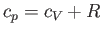

The previous two equations can be combined to give

|

(6.37) |

Now, by definition,

|

(6.38) |

so we obtain

|

(6.39) |

for an ideal gas. Note that, at constant volume,

all of the heat absorbed by the gas goes into increasing its internal energy,

and, hence, its temperature, whereas, at constant pressure, some of the absorbed

heat is used to do work on the environment as the volume increases. This

means that, in the latter case,

less heat is available to increase the temperature of the gas.

Thus, we expect the specific heat at constant pressure to exceed that at

constant volume, as indicated by the previous formula.

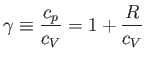

The ratio of the two specific heats,  , is conventionally denoted

, is conventionally denoted

. We have

. We have

|

(6.40) |

for an ideal gas. In fact,  is easy to measure experimentally because the speed

of sound in an ideal gas takes the form

is easy to measure experimentally because the speed

of sound in an ideal gas takes the form

|

(6.41) |

where  is the mass density.

(See Exercise 8.) Table 6.1

lists some experimental measurements

of

is the mass density.

(See Exercise 8.) Table 6.1

lists some experimental measurements

of  and

and  for common gases. The extent of the agreement between

for common gases. The extent of the agreement between  calculated from Equation (6.40) and the experimental

calculated from Equation (6.40) and the experimental  is remarkable.

is remarkable.

Table 6.1:

Molar specific heats of common gases in joules/mole/degree (at 15 C and 1

atmosphere). From Reif.

C and 1

atmosphere). From Reif.

| |

|

|

|

|

| Gas |

Symbol |

(experiment) |

(experiment) |

(theory) |

| Helium |

He |

12.5 |

1.666 |

1.666 |

| Argon |

Ar |

12.5 |

1.666 |

1.666 |

| Nitrogen |

|

20.6 |

1.405 |

1.407 |

| Oxygen |

|

21.1 |

1.396 |

1.397 |

| Carbon Dioxide |

|

28.2 |

1.302 |

1.298 |

| Ethane |

|

39.3 |

1.220 |

1.214 |

|

Next: Calculation of Specific Heats

Up: Classical Thermodynamics

Previous: Ideal Gas Equation of

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-25

![]() , no work is done by

the gas on its surroundings,

and the first law of thermodynamics reduces to

, no work is done by

the gas on its surroundings,

and the first law of thermodynamics reduces to

![]() , is conventionally denoted

, is conventionally denoted

![]() . We have

. We have