Next: Momentum Representation

Up: Fundamentals of Quantum Mechanics

Previous: Ehrenfest's Theorem

Operators

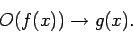

An operator,  (say), is a mathematical entity which transforms

one function into another: i.e.,

(say), is a mathematical entity which transforms

one function into another: i.e.,

|

(184) |

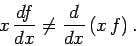

For instance,  is an operator, since

is an operator, since  is a different function

to

is a different function

to  , and is fully specified once

, and is fully specified once  is given. Furthermore,

is given. Furthermore,

is also an operator, since

is also an operator, since  is a different function

to

is a different function

to  , and is fully specified once

, and is fully specified once  is given.

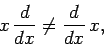

Now,

is given.

Now,

|

(185) |

This can also be written

|

(186) |

where the operators are assumed to act on everything to

their right, and a final  is understood [where

is understood [where  is a general function]. The above expression illustrates

an important point: i.e., in general, operators do not

commute. Of course, some operators do commute: e.g.,

is a general function]. The above expression illustrates

an important point: i.e., in general, operators do not

commute. Of course, some operators do commute: e.g.,

|

(187) |

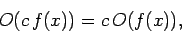

Finally, an operator,  , is termed linear if

, is termed linear if

|

(188) |

where  is a general function, and

is a general function, and  a general complex number.

All of the operators employed in quantum mechanics are linear.

a general complex number.

All of the operators employed in quantum mechanics are linear.

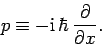

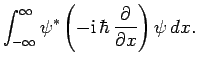

Now, from Eqs. (158) and (174),

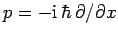

These expressions suggest a number of things. First, classical dynamical

variables, such as  and

and  , are represented in quantum mechanics

by linear operators which act on the wavefunction. Second,

displacement is represented by the algebraic operator

, are represented in quantum mechanics

by linear operators which act on the wavefunction. Second,

displacement is represented by the algebraic operator  ,

and momentum by the differential operator

,

and momentum by the differential operator

: i.e.,

: i.e.,

|

(191) |

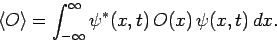

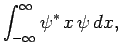

Finally, the expectation value of some dynamical variable represented by

the operator  is simply

is simply

|

(192) |

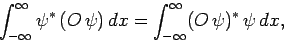

Clearly, if an operator is to represent a dynamical variable which has

physical significance then its expectation value must be real.

In other words, if the operator  represents a physical variable

then we require that

represents a physical variable

then we require that

, or

, or

|

(193) |

where  is the complex conjugate of

is the complex conjugate of  . An operator which

satisfies the above constraint is called an Hermitian operator.

It is easily demonstrated that

. An operator which

satisfies the above constraint is called an Hermitian operator.

It is easily demonstrated that  and

and  are both Hermitian.

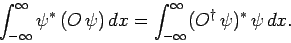

The Hermitian conjugate,

are both Hermitian.

The Hermitian conjugate,  , of

a general operator,

, of

a general operator,  , is defined as follows:

, is defined as follows:

|

(194) |

The Hermitian conjugate of an Hermitian operator is the same as the operator

itself: i.e.,  . For a non-Hermitian operator,

. For a non-Hermitian operator,  (say),

it is easily demonstrated that

(say),

it is easily demonstrated that

, and that the operator

, and that the operator  is Hermitian.

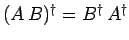

Finally, if

is Hermitian.

Finally, if  and

and  are two operators, then

are two operators, then

.

.

Suppose that we wish to find the operator which corresponds to the

classical dynamical variable  . In classical mechanics, there

is no difference between

. In classical mechanics, there

is no difference between  and

and  . However, in quantum

mechanics, we have already seen that

. However, in quantum

mechanics, we have already seen that  . So,

should be choose

. So,

should be choose  or

or  ? Actually, neither of these combinations

is Hermitian. However,

? Actually, neither of these combinations

is Hermitian. However,

![$(1/2) [x p + (x p)^\dag ]$](img554.png) is Hermitian.

Moreover,

is Hermitian.

Moreover,

![$(1/2) [x p + (x p)^\dag ]=(1/2) (x p+p^\dag x^\dag )=(1/2) (x p+p x)$](img555.png) , which neatly resolves

our problem of which order to put

, which neatly resolves

our problem of which order to put  and

and  .

.

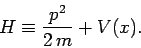

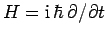

It is a reasonable guess that the operator corresponding to energy (which is

called the Hamiltonian, and conventionally denoted  ) takes the form

) takes the form

|

(195) |

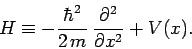

Note that  is Hermitian. Now, it follows from Eq. (191) that

is Hermitian. Now, it follows from Eq. (191) that

|

(196) |

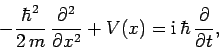

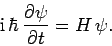

However, according to Schrödinger's equation, (137), we have

|

(197) |

so

|

(198) |

Thus, the time-dependent Schrödinger equation can be written

|

(199) |

Finally, if  is a classical dynamical variable which is

a function of displacement, momentum, and energy, then a reasonable

guess for the corresponding operator in quantum mechanics is

is a classical dynamical variable which is

a function of displacement, momentum, and energy, then a reasonable

guess for the corresponding operator in quantum mechanics is

![$(1/2) [O(x,p,H)+ O^\dag (x,p,H)]$](img563.png) , where

, where

, and

, and

.

.

Next: Momentum Representation

Up: Fundamentals of Quantum Mechanics

Previous: Ehrenfest's Theorem

Richard Fitzpatrick

2010-07-20

![]() represents a physical variable

then we require that

represents a physical variable

then we require that

![]() , or

, or

![]() . In classical mechanics, there

is no difference between

. In classical mechanics, there

is no difference between ![]() and

and ![]() . However, in quantum

mechanics, we have already seen that

. However, in quantum

mechanics, we have already seen that ![]() . So,

should be choose

. So,

should be choose ![]() or

or ![]() ? Actually, neither of these combinations

is Hermitian. However,

? Actually, neither of these combinations

is Hermitian. However,

![]() is Hermitian.

Moreover,

is Hermitian.

Moreover,

![]() , which neatly resolves

our problem of which order to put

, which neatly resolves

our problem of which order to put ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

![]() ) takes the form

) takes the form

![]() is a classical dynamical variable which is

a function of displacement, momentum, and energy, then a reasonable

guess for the corresponding operator in quantum mechanics is

is a classical dynamical variable which is

a function of displacement, momentum, and energy, then a reasonable

guess for the corresponding operator in quantum mechanics is

![]() , where

, where

![]() , and

, and

![]() .

.