Next: Hard Sphere Scattering

Up: Scattering Theory

Previous: Partial Waves

Let us now consider how the phase-shifts  in Eq. (1306) can be

evaluated. Consider a spherically symmetric potential

in Eq. (1306) can be

evaluated. Consider a spherically symmetric potential  which

vanishes for

which

vanishes for  , where

, where  is termed the range of the potential.

In the region

is termed the range of the potential.

In the region  , the wavefunction

, the wavefunction  satisfies the free-space Schrödinger equation (1285). The

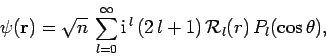

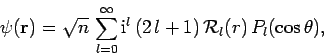

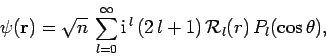

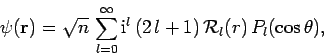

most general solution which is consistent with no incoming spherical-waves is

satisfies the free-space Schrödinger equation (1285). The

most general solution which is consistent with no incoming spherical-waves is

|

(1309) |

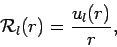

where

![\begin{displaymath}

{\cal R}_l(r) = \exp( {\rm i} \delta_l)

\left[\cos\delta_l j_l(k r) -\sin\delta_l y_l(k r)\right].

\end{displaymath}](img2944.png) |

(1310) |

Note that  functions are allowed to appear in the above

expression, because its region of validity does not include the origin

(where

functions are allowed to appear in the above

expression, because its region of validity does not include the origin

(where  ). The logarithmic derivative of the

). The logarithmic derivative of the  th

radial wavefunction,

th

radial wavefunction,

, just outside the range of the potential is given by

, just outside the range of the potential is given by

![\begin{displaymath}

\beta_{l+} = k a \left[\frac{ \cos\delta_l j_l'(k a) -

\s...

...}{\cos\delta_l

j_l(k a) - \sin\delta_l y_l(k a)}\right],

\end{displaymath}](img2947.png) |

(1311) |

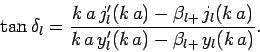

where  denotes

denotes  , etc. The above equation

can be inverted to give

, etc. The above equation

can be inverted to give

|

(1312) |

Thus, the problem of determining the phase-shift  is equivalent

to that of obtaining

is equivalent

to that of obtaining  .

.

The most general solution to Schrödinger's equation inside

the range of the potential ( ) which does not depend on the

azimuthal angle

) which does not depend on the

azimuthal angle  is

is

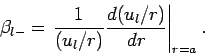

|

(1313) |

where

|

(1314) |

and

![\begin{displaymath}

\frac{d^2 u_l}{d r^2} +\left[k^2 -\frac{l (l+1)}{r^2} -\frac{2 m}{\hbar^2} V\right] u_l = 0.

\end{displaymath}](img2955.png) |

(1315) |

The boundary condition

|

(1316) |

ensures that the radial wavefunction is well-behaved at the

origin.

We can launch a well-behaved solution of the above equation from

, integrate out to

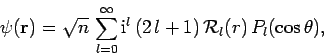

, integrate out to  , and form the logarithmic derivative

, and form the logarithmic derivative

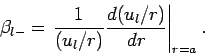

|

(1317) |

Since  and its first derivatives are necessarily continuous for

physically acceptible wavefunctions, it follows that

and its first derivatives are necessarily continuous for

physically acceptible wavefunctions, it follows that

|

(1318) |

The phase-shift  is then obtainable from Eq. (1312).

is then obtainable from Eq. (1312).

Next: Hard Sphere Scattering

Up: Scattering Theory

Previous: Partial Waves

Richard Fitzpatrick

2010-07-20

![\begin{displaymath}

\beta_{l+} = k a \left[\frac{ \cos\delta_l j_l'(k a) -

\s...

...}{\cos\delta_l

j_l(k a) - \sin\delta_l y_l(k a)}\right],

\end{displaymath}](img2947.png)

![]() ) which does not depend on the

azimuthal angle

) which does not depend on the

azimuthal angle ![]() is

is