Next: Helium Atom

Up: Variational Methods

Previous: Introduction

Suppose that we wish to solve the time-independent Schrödinger equation

|

(1167) |

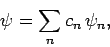

where  is a known (presumably complicated) time-independent Hamiltonian. Let

is a known (presumably complicated) time-independent Hamiltonian. Let  be a normalized trial solution to the above equation.

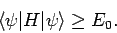

The variational principle states, quite simply, that the

ground-state energy,

be a normalized trial solution to the above equation.

The variational principle states, quite simply, that the

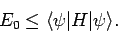

ground-state energy,  , is always less than or equal to the expectation

value of

, is always less than or equal to the expectation

value of  calculated with the trial wavefunction: i.e.,

calculated with the trial wavefunction: i.e.,

|

(1168) |

Thus, by varying  until the expectation value of

until the expectation value of  is minimized, we can

obtain an approximation to the wavefunction and energy of the ground-state.

is minimized, we can

obtain an approximation to the wavefunction and energy of the ground-state.

Let us prove the variational principle.

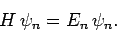

Suppose that the  and the

and the  are the true eigenstates and eigenvalues

of

are the true eigenstates and eigenvalues

of  : i.e.,

: i.e.,

|

(1169) |

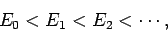

Furthermore, let

|

(1170) |

so that  is the ground-state,

is the ground-state,  the first excited state,

etc. The

the first excited state,

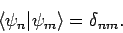

etc. The  are assumed to be orthonormal:

i.e.,

are assumed to be orthonormal:

i.e.,

|

(1171) |

If our trial wavefunction  is properly normalized then

we can write

is properly normalized then

we can write

|

(1172) |

where

|

(1173) |

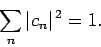

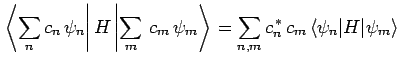

Now, the expectation value of  , calculated with

, calculated with  , takes the

form

, takes the

form

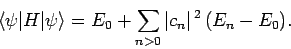

where use has been made of Eqs. (1169) and (1171).

So, we can write

|

(1175) |

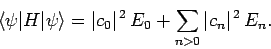

However, Eq. (1173) can be rearranged to give

|

(1176) |

Combining the previous two equations, we obtain

|

(1177) |

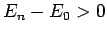

Now, the second term on the right-hand side of the above expression

is positive definite, since  for all

for all  [see (1170)].

Hence, we obtain the desired result

[see (1170)].

Hence, we obtain the desired result

|

(1178) |

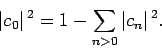

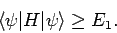

Suppose that we have found a good approximation,

, to the ground-state

wavefunction. If

, to the ground-state

wavefunction. If  is a normalized trial wavefunction which is

orthogonal to

is a normalized trial wavefunction which is

orthogonal to

(i.e.,

(i.e.,

)

then, by repeating the above analysis, we can easily demonstrate that

)

then, by repeating the above analysis, we can easily demonstrate that

|

(1179) |

Thus, by varying  until the expectation value of

until the expectation value of  is minimized, we can

obtain an approximation to the wavefunction and energy of the first excited state. Obviously, we can continue this process until we have approximations

to all of the stationary eigenstates. Note, however, that the errors are clearly cumulative in this method,

so that any approximations to highly excited states are unlikely to be very accurate. For this reason, the variational method is generally only

used to calculate the ground-state and first few excited states of

complicated quantum systems.

is minimized, we can

obtain an approximation to the wavefunction and energy of the first excited state. Obviously, we can continue this process until we have approximations

to all of the stationary eigenstates. Note, however, that the errors are clearly cumulative in this method,

so that any approximations to highly excited states are unlikely to be very accurate. For this reason, the variational method is generally only

used to calculate the ground-state and first few excited states of

complicated quantum systems.

Next: Helium Atom

Up: Variational Methods

Previous: Introduction

Richard Fitzpatrick

2010-07-20

![]() and the

and the ![]() are the true eigenstates and eigenvalues

of

are the true eigenstates and eigenvalues

of ![]() : i.e.,

: i.e.,

![]() , to the ground-state

wavefunction. If

, to the ground-state

wavefunction. If ![]() is a normalized trial wavefunction which is

orthogonal to

is a normalized trial wavefunction which is

orthogonal to

![]() (i.e.,

(i.e.,

![]() )

then, by repeating the above analysis, we can easily demonstrate that

)

then, by repeating the above analysis, we can easily demonstrate that