Next: Energy Levels of Hydrogen

Up: Orbital Angular Momentum

Previous: Eigenfunctions of Orbital Angular

Motion in Central Field

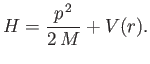

Consider a particle of mass  moving in a spherically symmetric potential.

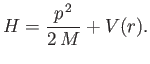

The Hamiltonian takes the form

moving in a spherically symmetric potential.

The Hamiltonian takes the form

|

(4.110) |

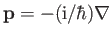

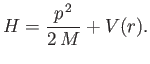

Adopting the Schrödinger representation, we can write

. Hence,

. Hence,

|

(4.111) |

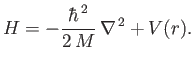

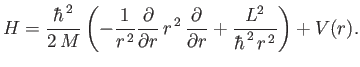

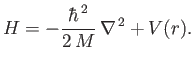

When written in spherical coordinates, the previous equation becomes [92]

![$\displaystyle H= -\frac{\hbar^{\,2}}{2\,M}\left[ \frac{1}{r^{\,2}}\frac{\partia...

...^{\,2}\sin^2\theta} \frac{\partial^{\,2}}{\partial\varphi^{\,2}}\right] + V(r).$](img1152.png) |

(4.112) |

Comparing this equation with Equation (4.85), we find that

|

(4.113) |

Now, we know that the three components of angular momentum commute with  . (See Section 4.1.) We also know, from Equations (4.80)-(4.82), that

. (See Section 4.1.) We also know, from Equations (4.80)-(4.82), that  ,

,  , and

, and  take the

form of partial derivative operators involving only angular coordinates,

when written in terms of spherical coordinates using the Schrödinger representation. It follows from Equation (4.113) that all three components of the angular

momentum commute with the Hamiltonian: that is,

take the

form of partial derivative operators involving only angular coordinates,

when written in terms of spherical coordinates using the Schrödinger representation. It follows from Equation (4.113) that all three components of the angular

momentum commute with the Hamiltonian: that is,

![$\displaystyle [{\bf L}, H] = {\bf0}.$](img1154.png) |

(4.114) |

It is also easily seen that  (which can be expressed as a purely angular differential operator) commutes with the Hamiltonian:

(which can be expressed as a purely angular differential operator) commutes with the Hamiltonian:

![$\displaystyle [L^2, H] = 0.$](img1155.png) |

(4.115) |

According to Section 3.3, the previous two equations

ensure that the angular momentum,  , and its magnitude squared,

, and its magnitude squared,  ,

are both constants of the motion. This is as expected for a spherically

symmetric potential.

,

are both constants of the motion. This is as expected for a spherically

symmetric potential.

Consider the energy eigenvalue problem

|

(4.116) |

where  is a number (with the dimensions of energy). Because

is a number (with the dimensions of energy). Because  and

and  commute with each other and

the Hamiltonian, it is always possible to represent the state of the

system in terms of the simultaneous eigenstates of

commute with each other and

the Hamiltonian, it is always possible to represent the state of the

system in terms of the simultaneous eigenstates of  ,

,  , and

, and  .

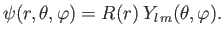

But, we already know that the most general form for the wavefunction of

a simultaneous

eigenstate of

.

But, we already know that the most general form for the wavefunction of

a simultaneous

eigenstate of  and

and  is

is

|

(4.117) |

(See the previous section.)

Substituting Equation (4.117) into Equation (4.113), and making use of Equation (4.105), we

obtain

![$\displaystyle \left[\frac{\hbar^{\,2}}{2\,M} \left(-\frac{1}{r^{\,2}} \frac{d}{...

...r^{\,2}\,\frac{d}{dr} +\frac{l\,(l+1)}{r^{\,2}}\right) + V(r) - E\right] R = 0.$](img1159.png) |

(4.118) |

This is a Sturm-Liouville equation for the function  [92]. We know,

from the general properties of this type of equation,

that if

[92]. We know,

from the general properties of this type of equation,

that if  is required to be well behaved at

is required to be well behaved at  , and as

, and as

, then solutions only exist for a discrete set of values of

, then solutions only exist for a discrete set of values of  . These

are the energy eigenvalues, and are conventionally labeled using a quantum number denoted

. These

are the energy eigenvalues, and are conventionally labeled using a quantum number denoted  . (Thus,

. (Thus,

corresponds to the lowest energy state,

corresponds to the lowest energy state,  to the next lowest energy state, and so on.) In general, the energy eigenvalues depend

on the quantum numbers

to the next lowest energy state, and so on.) In general, the energy eigenvalues depend

on the quantum numbers  and

and  , but are independent of the quantum number

, but are independent of the quantum number  .

.

Next: Energy Levels of Hydrogen

Up: Orbital Angular Momentum

Previous: Eigenfunctions of Orbital Angular

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-22

![$\displaystyle H= -\frac{\hbar^{\,2}}{2\,M}\left[ \frac{1}{r^{\,2}}\frac{\partia...

...^{\,2}\sin^2\theta} \frac{\partial^{\,2}}{\partial\varphi^{\,2}}\right] + V(r).$](img1152.png)

![]() . (See Section 4.1.) We also know, from Equations (4.80)-(4.82), that

. (See Section 4.1.) We also know, from Equations (4.80)-(4.82), that ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() take the

form of partial derivative operators involving only angular coordinates,

when written in terms of spherical coordinates using the Schrödinger representation. It follows from Equation (4.113) that all three components of the angular

momentum commute with the Hamiltonian: that is,

take the

form of partial derivative operators involving only angular coordinates,

when written in terms of spherical coordinates using the Schrödinger representation. It follows from Equation (4.113) that all three components of the angular

momentum commute with the Hamiltonian: that is,