Next: Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle

Up: Position and Momentum

Previous: Generalized Schrödinger Representation

Momentum Representation

Consider a system with one degree of freedom, describable in terms of a coordinate

and its conjugate momentum

and its conjugate momentum  , both of which have a continuous range of

eigenvalues. We have seen that it is possible to represent the system in terms

of the eigenkets of

, both of which have a continuous range of

eigenvalues. We have seen that it is possible to represent the system in terms

of the eigenkets of  .

This is termed the Schrödinger representation.

However, it is also possible to represent the system in

terms of the eigenkets of

.

This is termed the Schrödinger representation.

However, it is also possible to represent the system in

terms of the eigenkets of  .

.

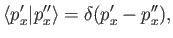

Consider the eigenkets of  that belong to the eigenvalues

that belong to the eigenvalues  . These are

denoted

. These are

denoted

. The orthogonality relation for the momentum eigenkets is

. The orthogonality relation for the momentum eigenkets is

|

(2.80) |

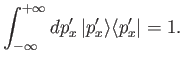

and the corresponding completeness relation is

|

(2.81) |

A general state ket can be written

|

(2.82) |

where the standard ket  satisfies

satisfies

|

(2.83) |

Note that the standard ket in this representation is quite

different to that in the Schrödinger representation.

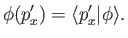

The momentum space wavefunction

satisfies

satisfies

|

(2.84) |

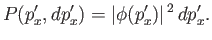

The probability that a measurement of the momentum yields a result

lying in the range  to

to

is given by

is given by

|

(2.85) |

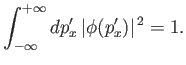

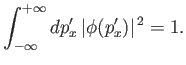

Finally, the normalization condition for a physical momentum space wavefunction is

|

(2.86) |

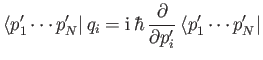

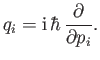

The fundamental commutation relations (2.23)-(2.25) exhibit a

particular symmetry between coordinates and their conjugate momenta. In fact, if all the

coordinates are transformed into their conjugate momenta, and vice versa, and

is then replaced by

is then replaced by  , then the commutation relations are

unchanged. It follows from this symmetry that we can always choose the eigenkets

of

, then the commutation relations are

unchanged. It follows from this symmetry that we can always choose the eigenkets

of  in such a manner that the coordinate

in such a manner that the coordinate

can be represented as

can be represented as

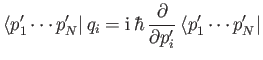

|

(2.87) |

(See Section 2.4.)

This scheme is termed the momentum representation.

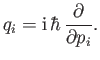

The previous result is easily generalized to a system with more than one degree of

freedom. Suppose the system is specified by  coordinates,

coordinates,

, and

, and

conjugate momenta,

conjugate momenta,

. Then, in the momentum representation, the

coordinates can be written as

. Then, in the momentum representation, the

coordinates can be written as

|

(2.88) |

We also have

|

(2.89) |

and

|

(2.90) |

[cf., Equation (2.78).]

Generally speaking, the momentum representation is less useful than the Schrödinger representation. The

main reason for this is that the energy operators (i.e., the Hamiltonians) of

most simple microscopic systems take the form of a sum of quadratic terms in the momenta

(i.e., the kinetic energy) plus a complicated function of the coordinates

(i.e., the potential energy). In the Schrödinger representation,

the eigenvalue problem for the energy translates into a second-order partial differential

equation in the coordinates, with a complicated potential function. In the

momentum representation, the problem transforms into a high-order partial differential

equation in the momenta, with a quadratic potential. With the mathematical

tools at our disposal, we are far better able to solve the former type of differential equation

than the latter.

Next: Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle

Up: Position and Momentum

Previous: Generalized Schrödinger Representation

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-22

![]() that belong to the eigenvalues

that belong to the eigenvalues ![]() . These are

denoted

. These are

denoted

![]() . The orthogonality relation for the momentum eigenkets is

. The orthogonality relation for the momentum eigenkets is

![]() is then replaced by

is then replaced by ![]() , then the commutation relations are

unchanged. It follows from this symmetry that we can always choose the eigenkets

of

, then the commutation relations are

unchanged. It follows from this symmetry that we can always choose the eigenkets

of ![]() in such a manner that the coordinate

in such a manner that the coordinate

![]() can be represented as

can be represented as

![]() coordinates,

coordinates,

![]() , and

, and

![]() conjugate momenta,

conjugate momenta,

![]() . Then, in the momentum representation, the

coordinates can be written as

. Then, in the momentum representation, the

coordinates can be written as