Next: Optical Theorem

Up: Scattering Theory

Previous: Born Expansion

Partial Waves

We can assume, without loss of generality, that the incident wavefunction

is characterized by a wavevector,  , that is aligned parallel to the

, that is aligned parallel to the  -axis.

The scattered wavefunction is characterized by a wavevector,

-axis.

The scattered wavefunction is characterized by a wavevector,  ,

that has the same magnitude as

,

that has the same magnitude as  , but, in general, points

in a different direction. The direction of

, but, in general, points

in a different direction. The direction of  is specified

by the polar angle

is specified

by the polar angle  (i.e., the angle subtended between the

two wavevectors), and an azimuthal angle

(i.e., the angle subtended between the

two wavevectors), and an azimuthal angle  measured about the

measured about the  -axis.

Equations (10.33) and (10.34) strongly suggest that for a spherically symmetric

scattering potential [i.e.,

-axis.

Equations (10.33) and (10.34) strongly suggest that for a spherically symmetric

scattering potential [i.e.,

], the scattering amplitude

is a function of

], the scattering amplitude

is a function of  only: that is,

only: that is,

|

(10.53) |

Let us assume that this is the case.

It follows that neither the incident wavefunction,

|

(10.54) |

[see Equation (10.14)], nor the total wavefunction far from the scattering region,

![$\displaystyle \psi({\bf x}) = \frac{1}{(2\pi)^{3/2}} \left[ \exp(\,{\rm i}\,k\,r\cos\theta) + \frac{\exp(\,{\rm i}\,k\,r)\, f(\theta)} {r} \right]$](img3518.png) |

(10.55) |

[see Equation (10.20)], depend on the azimuthal angle,  .

.

Outside the range of the scattering potential,

and

and

both satisfy the free-space Schrödinger equation,

both satisfy the free-space Schrödinger equation,

|

(10.56) |

Consider the most general solution to this equation that is independent of the azimuthal angle,  .

Separation of variables (in spherical coordinates) yields

.

Separation of variables (in spherical coordinates) yields

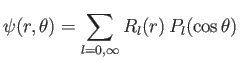

|

(10.57) |

(See Exercise 10.)

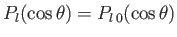

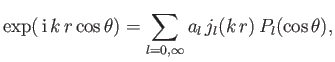

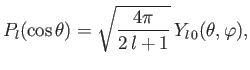

The Legendre polynomials,

, are related to the

associated Legendre functions,

, are related to the

associated Legendre functions,

, as well as the spherical harmonics,

, as well as the spherical harmonics,

, introduced in Section 4.4, via

, introduced in Section 4.4, via

, and

, and

|

(10.58) |

respectively.

Equations (10.56) and (10.57) can be combined to give

![$\displaystyle r^{\,2} \,\frac{d^{\,2} R_l}{dr^{\,2}} + 2\,r\,\frac{dR_l}{dr} + [k^{\,2} \,r^{\,2} - l\,(l+1)]\,R_l = 0.$](img3525.png) |

(10.59) |

(See Exercise 10.)

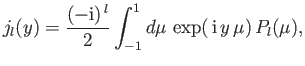

The two independent solutions to this equation are the

spherical Bessel function,  , and the Neumann function,

, and the Neumann function,

,

where

,

where

[1].

Note that spherical Bessel functions are well behaved in the limit

, whereas Neumann functions become singular.

The asymptotic behavior of these functions in the limit

, whereas Neumann functions become singular.

The asymptotic behavior of these functions in the limit

is

is

[1].

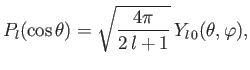

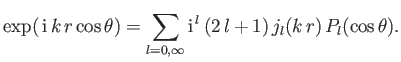

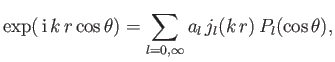

We can write

|

(10.64) |

where the  are constants. Of course, there are no Neumann functions in

this expansion because they are not well behaved as

are constants. Of course, there are no Neumann functions in

this expansion because they are not well behaved as

(whereas the function on the

left-hand side is clearly finite at

(whereas the function on the

left-hand side is clearly finite at  ).

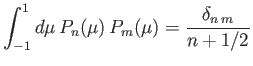

As is well known, the Legendre polynomials are orthogonal functions,

).

As is well known, the Legendre polynomials are orthogonal functions,

|

(10.65) |

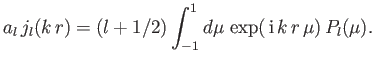

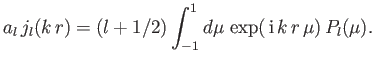

[1], so we can invert the preceding expansion to give

|

(10.66) |

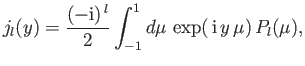

Now,

|

(10.67) |

for

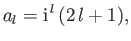

[1]. Thus, a comparison of the previous two equations yields

[1]. Thus, a comparison of the previous two equations yields

|

(10.68) |

giving

|

(10.69) |

The preceding expression specifies how

a plane wave can be decomposed into

a series of spherical waves. The latter waves are usually referred to as partial waves.

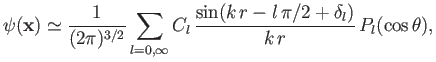

The most general expression for the total wavefunction outside the

scattering region is

![$\displaystyle \psi({\bf x}) = \frac{1}{(2\pi)^{3/2}} \sum_{l=0,\infty}\left[ A_l\,j_l(k\,r) + B_l\,\eta_l(k\,r)\right] P_l(\cos\theta),$](img3542.png) |

(10.70) |

where the  and

and  are constants.

Note that the Neumann functions are allowed to appear

in this expansion, because

its region of validity does not include the origin. In the large-

are constants.

Note that the Neumann functions are allowed to appear

in this expansion, because

its region of validity does not include the origin. In the large- limit, the total wavefunction reduces to

limit, the total wavefunction reduces to

![$\displaystyle \psi ({\bf x} ) \simeq \frac{1}{(2\pi)^{3/2}} \sum_{l=0,\infty}\l...

...\pi/2)}{k\,r} - B_l\,\frac{\cos(k\,r -l\,\pi/2)}{k\,r} \right] P_l(\cos\theta),$](img3545.png) |

(10.71) |

where use has been made of Equations (10.62) and (10.63). The previous expression can also

be written

|

(10.72) |

where

Equation (10.72) yields

![$\displaystyle \psi({\bf x}) \simeq \frac{1}{(2\pi)^{3/2}} \sum_{l=0,\infty} C_l...

...rm i}\,(k\,r - l\,\pi/2+ \delta_l)} }{2\,{\rm i}\,k\,r}\right] P_l(\cos\theta),$](img3551.png) |

(10.75) |

which contains both incoming and outgoing spherical waves. What is the

source of the incoming waves? Obviously, they must form part of

the large- asymptotic expansion of the incident wavefunction. In fact,

it is easily seen from Equations (10.54), (10.62), and (10.69) that

asymptotic expansion of the incident wavefunction. In fact,

it is easily seen from Equations (10.54), (10.62), and (10.69) that

![$\displaystyle \phi({\bf x}) \simeq \frac{1}{(2\pi)^{3/2}} \sum_{l=0,\infty} {\r...

...{\rm e}^{-{\rm i}\,(k\,r - l\,\pi/2)}}{2\,{\rm i}\,k\,r}\right]P_l(\cos\theta),$](img3552.png) |

(10.76) |

in the large- limit. Now, Equations (10.54) and (10.55) give

limit. Now, Equations (10.54) and (10.55) give

![$\displaystyle (2\pi)^{3/2}\,[\psi({\bf x} )- \phi({\bf x}) ] = \frac{\exp(\,{\rm i}\,k\,r)}{r}\, f(\theta).$](img3553.png) |

(10.77) |

Note that the right-hand side consists only of an outgoing spherical

wave. This implies that the coefficients of the incoming spherical waves

in the large- expansions of

expansions of

and

and

must be equal. It follows from Equations (10.75) and (10.76) that

must be equal. It follows from Equations (10.75) and (10.76) that

![$\displaystyle C_l = (2\,l+1)\,\exp[\,{\rm i}\,(\delta_l + l\,\pi/2)],$](img3554.png) |

(10.78) |

which leads to

Thus, it is apparent that the effect of the scattering is to introduce a phase-shift,  , into the

, into the

th partial wave.

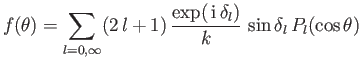

Finally, Equation (10.77) yields

th partial wave.

Finally, Equation (10.77) yields

|

(10.81) |

[42].

Clearly, determining the scattering amplitude,

, via a decomposition into

partial waves (i.e., spherical waves), is equivalent to determining

the phase-shifts,

, via a decomposition into

partial waves (i.e., spherical waves), is equivalent to determining

the phase-shifts,  .

.

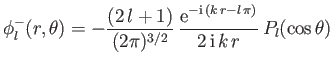

It is helpful to write

where

|

(10.84) |

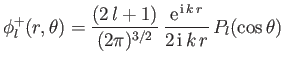

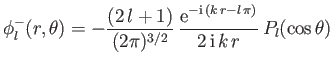

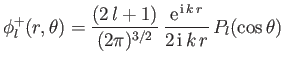

is an ingoing spherical wave, whereas

|

(10.85) |

is an outgoing spherical wave. Moreover,

|

(10.86) |

[See Equations (10.79) and (10.80).]

Note that

and

and

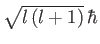

are both eigenstates of the magnitude of the total

orbital angular momentum about the origin belonging to the eigenvalues

are both eigenstates of the magnitude of the total

orbital angular momentum about the origin belonging to the eigenvalues

. (See Chapter 4.)

Thus, in preforming a partial wave expansion, we have effectively separated the incoming and outgoing particles into

streams possessing definite angular momenta about the origin. Moreover, the effect of the scattering is to introduce an

angular-momentum-dependent

phase-shift into the outgoing particle streams.

. (See Chapter 4.)

Thus, in preforming a partial wave expansion, we have effectively separated the incoming and outgoing particles into

streams possessing definite angular momenta about the origin. Moreover, the effect of the scattering is to introduce an

angular-momentum-dependent

phase-shift into the outgoing particle streams.

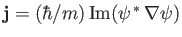

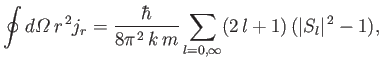

The net outward particle flux through a sphere of radius  , centered on the origin, is proportional to

, centered on the origin, is proportional to

|

(10.87) |

where

is the probability current. It follows that

is the probability current. It follows that

|

(10.88) |

where use has been made of Equation (10.65).

Of course, the net particle flux must be zero, otherwise the number of particles would not be

conserved. Particle conservation is ensured by the fact that  for all

for all  . [See Equation (10.86).]

. [See Equation (10.86).]

Next: Optical Theorem

Up: Scattering Theory

Previous: Born Expansion

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-22

![]() and

and

![]() both satisfy the free-space Schrödinger equation,

both satisfy the free-space Schrödinger equation,

![$\displaystyle \psi ({\bf x} ) \simeq \frac{1}{(2\pi)^{3/2}} \sum_{l=0,\infty}\l...

...\pi/2)}{k\,r} - B_l\,\frac{\cos(k\,r -l\,\pi/2)}{k\,r} \right] P_l(\cos\theta),$](img3545.png)

![$\displaystyle =\sum_{l=0,\infty} \left[\phi_l^+(r,\theta)+\phi_l^-(r,\theta)\right],$](img3562.png)

![$\displaystyle =\sum_{l=0,\infty} \left[S_l\,\phi_l^+(r,\theta)+\phi_l^-(r,\theta)\right],$](img3564.png)

![]() , centered on the origin, is proportional to

, centered on the origin, is proportional to