Next: Solar Wind Up: Magnetohydrodynamic Fluids Previous: Flux Freezing Contents

|

|

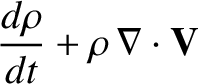

(8.22) |

|

|

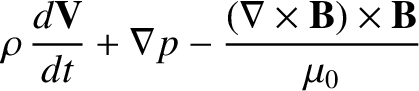

(8.23) |

|

|

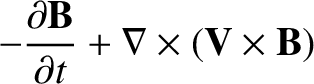

(8.24) |

|

|

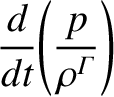

(8.25) |

,

,  , and

, and  are

constants in a spatially uniform plasma.

are

constants in a spatially uniform plasma.

Let us search for wave-like solutions to Equations (8.26)–(8.29) in which perturbed

quantities vary like

![$\exp[\,{\rm i}\,({\bf k}\cdot{\bf r}-\omega\,t)]$](img1871.png) .

It follows that

.

It follows that

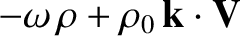

|

|

(8.30) |

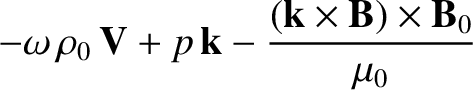

|

|

(8.31) |

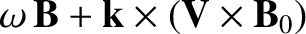

|

|

(8.32) |

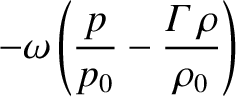

|

|

(8.33) |

, the previous equations yield

Substitution of these expressions into the linearized equation of

motion, Equation (8.31), gives

, the previous equations yield

Substitution of these expressions into the linearized equation of

motion, Equation (8.31), gives

We can assume, without loss of generality, that the equilibrium magnetic

field,  ,

is directed along the

,

is directed along the  -axis, and that the wavevector,

-axis, and that the wavevector,  , lies

in the

, lies

in the  -

- plane. Let

plane. Let  be the angle subtended between

be the angle subtended between  and

and

. Equation (8.37) reduces to the eigenvalue

equation

. Equation (8.37) reduces to the eigenvalue

equation

There are three independent roots of the previous dispersion relation, corresponding to the three different types of wave that can propagate through an MHD plasma. The first, and most obvious, root is

which has the associated eigenvector . This

root is characterized by both

. This

root is characterized by both

and

and

. It immediately follows from Equations (8.34) and (8.35) that there is

zero perturbation of the plasma density or pressure

associated with the root. In fact, this particular root can easily be

identified as the shear-Alfvén wave

introduced in Section 5.8. The properties of the shear-Alfvén wave in a warm (i.e., non-zero

pressure) plasma are unchanged from those found earlier in a cold plasma.

Finally, because the shear-Alfvén wave only involves plasma

motion perpendicular to the magnetic field, we would expect the

dispersion relation (8.42) to hold good in a collisionless, as well as a

collisional, plasma.

. It immediately follows from Equations (8.34) and (8.35) that there is

zero perturbation of the plasma density or pressure

associated with the root. In fact, this particular root can easily be

identified as the shear-Alfvén wave

introduced in Section 5.8. The properties of the shear-Alfvén wave in a warm (i.e., non-zero

pressure) plasma are unchanged from those found earlier in a cold plasma.

Finally, because the shear-Alfvén wave only involves plasma

motion perpendicular to the magnetic field, we would expect the

dispersion relation (8.42) to hold good in a collisionless, as well as a

collisional, plasma.

The remaining two roots of the dispersion relation (8.41) are written

and respectively. Here, Note that . The first root is generally termed the

fast magnetosonic wave, or fast wave, for short, whereas

the second root is usually called the slow magnetosonic

wave, or slow wave. The eigenvectors for these waves are

. The first root is generally termed the

fast magnetosonic wave, or fast wave, for short, whereas

the second root is usually called the slow magnetosonic

wave, or slow wave. The eigenvectors for these waves are

. It follows that

. It follows that

and

and

. Hence, these waves are associated with non-zero perturbations

in the plasma density and pressure, and also involve plasma motion parallel, as

well as perpendicular, to the magnetic field. The latter observation suggests

that the dispersion relations

(8.43) and (8.44) are likely to undergo significant modification in

collisionless plasmas.

. Hence, these waves are associated with non-zero perturbations

in the plasma density and pressure, and also involve plasma motion parallel, as

well as perpendicular, to the magnetic field. The latter observation suggests

that the dispersion relations

(8.43) and (8.44) are likely to undergo significant modification in

collisionless plasmas.

In order to better understand the nature of the fast and slow waves, let us

consider the cold plasma limit, which is obtained by letting the sound

speed,  , tend to zero. In this limit, the slow wave ceases to exist (in fact,

its phase-velocity tends to zero), whereas the dispersion relation for

the fast wave reduces to

, tend to zero. In this limit, the slow wave ceases to exist (in fact,

its phase-velocity tends to zero), whereas the dispersion relation for

the fast wave reduces to

|

(8.46) |

In the limit

, which is appropriate to low-

, which is appropriate to low- plasmas (see

Section 4.16), the dispersion relation for the slow wave reduces to

plasmas (see

Section 4.16), the dispersion relation for the slow wave reduces to

|

(8.47) |

plasmas, the slow

wave is a sound wave modified by the presence of the magnetic field.

plasmas, the slow

wave is a sound wave modified by the presence of the magnetic field.

The distinction between the fast and slow waves can be further understood

by comparing the signs of the wave-induced fluctuations in the plasma and magnetic

pressures:  and

and

, respectively.

It follows from Equation (8.36) that

, respectively.

It follows from Equation (8.36) that

-component of Equation (8.31) yields

Combining Equations (8.35), (8.39), (8.40), (8.48), and (8.49), we obtain

-component of Equation (8.31) yields

Combining Equations (8.35), (8.39), (8.40), (8.48), and (8.49), we obtain

|

(8.50) |

and

and

have the same sign

if

have the same sign

if

, and the opposite sign if

, and the opposite sign if

. Here,

. Here,

is the phase-velocity. It is

straightforward to show that

is the phase-velocity. It is

straightforward to show that

, and

, and

.

Thus, we conclude that the plasma pressure and

magnetic pressure fluctuations reinforce one another in the fast magnetosonic wave, whereas the

fluctuations oppose one another in the slow magnetosonic wave.

.

Thus, we conclude that the plasma pressure and

magnetic pressure fluctuations reinforce one another in the fast magnetosonic wave, whereas the

fluctuations oppose one another in the slow magnetosonic wave.

![\includegraphics[height=3in]{Chapter08/fig8_1.eps}](img2748.png) |

Figure 8.1 shows the variation of the phase velocities of the three MHD waves with direction of propagation in the

-

- plane for a low-

plane for a low- plasma in which

plasma in which  . It can be

seen that the slow wave always has a smaller phase-velocity than the

shear-Alfvén wave, which, in turn, always has a smaller phase-velocity than the fast wave.

. It can be

seen that the slow wave always has a smaller phase-velocity than the

shear-Alfvén wave, which, in turn, always has a smaller phase-velocity than the fast wave.

The existence of MHD waves was first predicted theoretically by Alfvén (Alfvén 1942). These waves were subsequently observed in the laboratory—first in magnetized conducting fluids (e.g., mercury) (Lundquist 1949), and then in magnetized plasmas (Wilcox, Boley, and DeSilva 1960).