Next: Boltzmann H-Theorem Up: Collisions Previous: Rosenbluth Potentials Contents

is small,

Obviously, the integral appearing in the previous expression diverges at both large and small

is small,

Obviously, the integral appearing in the previous expression diverges at both large and small  .

.

The divergence of the integral on the right-hand side of the previous equation at large  is a consequence of the breakdown of the small-angle approximation. The standard prescription

for avoiding this divergence is to truncate the integral at some

is a consequence of the breakdown of the small-angle approximation. The standard prescription

for avoiding this divergence is to truncate the integral at some

above which the small-angle approximation becomes

invalid. According to Equation (3.84), this truncation is equivalent to neglecting all collisions whose impact parameters

fall below the value

above which the small-angle approximation becomes

invalid. According to Equation (3.84), this truncation is equivalent to neglecting all collisions whose impact parameters

fall below the value

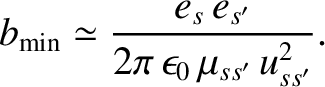

|

(3.115) |

is the idea that Coulomb collisions are dominated by small-angle scattering events, and that

the occasional large-angle scattering events have a negligible effect on the scattering statistics. Unfortunately, this is not quite true (if it were then the integral would converge at large

is the idea that Coulomb collisions are dominated by small-angle scattering events, and that

the occasional large-angle scattering events have a negligible effect on the scattering statistics. Unfortunately, this is not quite true (if it were then the integral would converge at large  ). However, the

rare large-angle scattering events only make a relatively weak logarithmic contribution to the scattering statistics.

). However, the

rare large-angle scattering events only make a relatively weak logarithmic contribution to the scattering statistics.

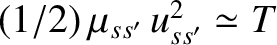

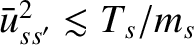

Making the estimate

, where

, where  is the assumed common temperature of the

two colliding species, we obtain

is the assumed common temperature of the

two colliding species, we obtain

is the classical distance of closest approach introduced in Section 1.6.

However, as mentioned in Section 1.10, it is possible for the classical distance of closest approach

to fall below the de Broglie wavelength of one or both of the colliding particles, even in the case of a weakly coupled plasma.

In this situation, the most sensible thing to do is to approximate

is the classical distance of closest approach introduced in Section 1.6.

However, as mentioned in Section 1.10, it is possible for the classical distance of closest approach

to fall below the de Broglie wavelength of one or both of the colliding particles, even in the case of a weakly coupled plasma.

In this situation, the most sensible thing to do is to approximate

as the larger de Broglie wavelength (Spitzer 1956; Braginskii 1965).

as the larger de Broglie wavelength (Spitzer 1956; Braginskii 1965).

The divergence of the integral on the right-hand side of Equation (3.114) at small  is a consequence of the

infinite range of the Coulomb potential. The standard prescription

for avoiding this divergence is to take the Debye shielding of the Coulomb potential into account. (See Section 1.5.) This is equivalent to

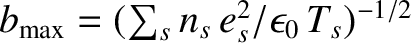

neglecting all collisions whose impact parameters exceed the value

is a consequence of the

infinite range of the Coulomb potential. The standard prescription

for avoiding this divergence is to take the Debye shielding of the Coulomb potential into account. (See Section 1.5.) This is equivalent to

neglecting all collisions whose impact parameters exceed the value

is the Debye length. Of course, Debye shielding is a many-particle effect. Hence, the Landau collision operator can no longer be regarded as a

pure two-body collision operator. Fortunately, however, many-particle effects only make a relatively weak logarithmic contribution to the operator.

is the Debye length. Of course, Debye shielding is a many-particle effect. Hence, the Landau collision operator can no longer be regarded as a

pure two-body collision operator. Fortunately, however, many-particle effects only make a relatively weak logarithmic contribution to the operator.

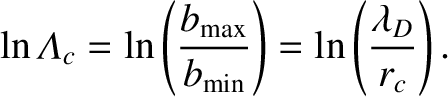

According to Equations (3.86), (3.116), and (3.117),

|

(3.118) |

|

(3.119) |

lies in the range

lies in the range

–

– for typical weakly coupled plasmas. It also follows that

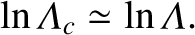

for typical weakly coupled plasmas. It also follows that

in a

weakly coupled plasma, which means that there is a large range of impact parameters for which it is accurate to treat Coulomb collisions

as small-angle two-body scattering events.

in a

weakly coupled plasma, which means that there is a large range of impact parameters for which it is accurate to treat Coulomb collisions

as small-angle two-body scattering events.

The conventional definition of the Coulomb logarithm is as follows (Richardson 2019). For a species- particle,

with mass

particle,

with mass  , charge

, charge  , number density

, number density  , and temperature

, and temperature  , scattered by species-

, scattered by species- particles, with mass

particles, with mass  , charge

, charge  ,

number density

,

number density  , and temperature

, and temperature  ,

the Coulomb logarithm is defined

,

the Coulomb logarithm is defined

. Here,

. Here,

is the larger of

is the larger of

and

and

, averaged over both particle

distributions, where

, averaged over both particle

distributions, where

and

and

. Furthermore,

. Furthermore,

, where the

summation extends over all species,

, where the

summation extends over all species,  , for which

, for which

.

.

Consider a quasi-neutral plasma consisting of electrons of mass  , charge

, charge  , number density

, number density  ,

and temperature

,

and temperature  , and ions of mass

, and ions of mass  , charge

, charge  , number density

, number density  , and temperature

, and temperature  .

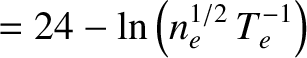

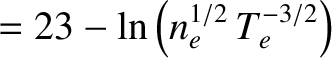

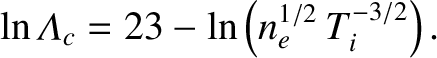

For thermal (i.e., Maxwellian) electron-electron collisions, we obtain (Richardson 2019)

.

For thermal (i.e., Maxwellian) electron-electron collisions, we obtain (Richardson 2019)

![$\displaystyle \ln{\mit\Lambda}_c = 23.5 - \ln\left(n_e^{1/2}\,T_e^{-5/4}\right)-\left[10^{-5} + (\ln T_e-2)^2/16\right]^{1/2}.$](img840.png) |

(3.120) |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

(3.121) |

|

(3.122) |

is measured in units of

is measured in units of

, and all species temperatures are measured in units of

electron-volts.

, and all species temperatures are measured in units of

electron-volts.

The standard approach in plasma physics is to treat the Coulomb logarithm as a constant, with a value determined by the ambient

electron number density, and the ambient electron and ion temperatures, as has just been described. This approximation ensures that the Landau collision

operator,

, is strictly bilinear in its two arguments.

, is strictly bilinear in its two arguments.