Next: Rutherford Scattering Cross-Section

Up: Collisions

Previous: Boltzmann H-Theorem

Two-Body Coulomb Collisions

Consider a two-body Coulomb collision between a particle of species  , with mass

, with mass  and charge

and charge  , and a particle of species

, and a particle of species  ,

with mass

,

with mass  and charge

and charge  . The equations of motion of the two particles take the form

. The equations of motion of the two particles take the form

where

|

(3.58) |

Here,  and

and  are the respective position vectors, and

are the respective position vectors, and

is

the relative position vector.

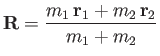

It is easily demonstrated that

is

the relative position vector.

It is easily demonstrated that

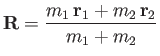

where

|

(3.61) |

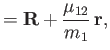

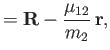

is the vector position of the center of mass (which does not accelerate), and

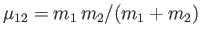

the reduced mass. Equations (3.56) and (3.57) can be combined to give a single

equation of relative motion,

the reduced mass. Equations (3.56) and (3.57) can be combined to give a single

equation of relative motion,

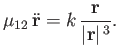

|

(3.62) |

Two relations that immediately follow from the previous equation are

where

|

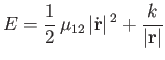

(3.65) |

is the conserved angular momentum per unit mass, and

|

(3.66) |

the conserved energy.

Equation (3.65) implies that

. This is the equation of a plane that passes through the origin, and whose normal is parallel

to the constant vector

. This is the equation of a plane that passes through the origin, and whose normal is parallel

to the constant vector  . We, therefore, conclude that the relative position vector

. We, therefore, conclude that the relative position vector  is constrained to lie in this plane,

which implies that the trajectories of both colliding particles are coplanar.

Let the plane

is constrained to lie in this plane,

which implies that the trajectories of both colliding particles are coplanar.

Let the plane

coincide with the

coincide with the  -

- plane, so that we can write

plane, so that we can write

. It is convenient to

define the standard plane polar coordinates

. It is convenient to

define the standard plane polar coordinates

and

and

.

When expressed in terms of these coordinates, the conserved angular momentum per unit mass becomes

.

When expressed in terms of these coordinates, the conserved angular momentum per unit mass becomes

|

(3.67) |

where

|

(3.68) |

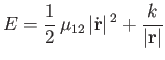

Furthermore, the conserved energy takes the form

|

(3.69) |

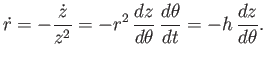

Suppose that

, where

, where

and

and

. It follows that

. It follows that

|

(3.70) |

Hence, Equation (3.69) transforms to give

![$\displaystyle E = \frac{1}{2}\,\mu_{12}\,h^2\left[\left(\frac{dz}{d\theta}\right)^2 + z^2\right] + k\,z.$](img730.png) |

(3.71) |

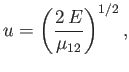

It is convenient to define the relative velocity at large distances,

|

(3.72) |

as well as the impact parameter,

|

(3.73) |

The latter parameter is simply the distance of closest approach of the two particles in the situation in which there is no Coulomb force acting between them,

and they, consequently, move in straight-lines. (See Figure 3.1.) The previous three equations can be combined to give

|

(3.74) |

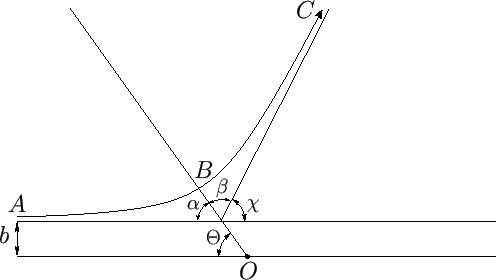

Figure 3.1:

A two-body Coulomb collision.

|

Figure 3.1 shows the collision in a frame of reference in which particle  remains stationary at the origin,

remains stationary at the origin,  ,

whereas particle

,

whereas particle  traces out the path

traces out the path  . Point

. Point  corresponds to the closest approach of the

two particles. It follows, by symmetry (because Coulomb collisions are reversible), that the angles

corresponds to the closest approach of the

two particles. It follows, by symmetry (because Coulomb collisions are reversible), that the angles  and

and  shown in the figure are equal to one another. Hence, we deduce that

shown in the figure are equal to one another. Hence, we deduce that

|

(3.75) |

Here,  is the angle through which the path of particle

is the angle through which the path of particle  (or particle

(or particle  ) is deviated as a consequence of the collision,

whereas

) is deviated as a consequence of the collision,

whereas

is the angle through which the relative position vector,

is the angle through which the relative position vector,  , rotates as particle

, rotates as particle  moves from point

moves from point  (which is assumed to be infinity far from point

(which is assumed to be infinity far from point  ) to point

) to point  . Suppose that point

. Suppose that point  corresponds to

corresponds to  . It follows that

. It follows that

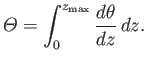

|

(3.76) |

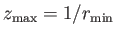

Here,

, where

, where

is the distance of closest approach.

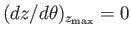

Now, by symmetry,

is the distance of closest approach.

Now, by symmetry,

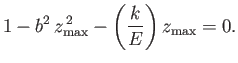

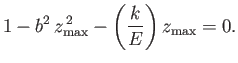

, so Equation (3.74) implies that

, so Equation (3.74) implies that

|

(3.77) |

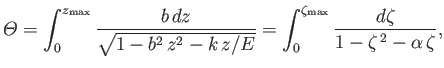

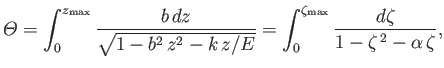

Combining Equations (3.74) and (3.76), we obtain

|

(3.78) |

where

, and

, and

|

(3.79) |

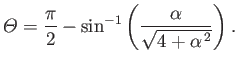

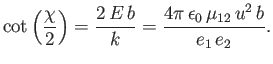

Integration (Speigel, Liu, and Lipschutz 1999) yields

|

(3.80) |

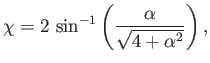

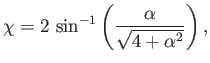

Hence, from Equation (3.75), we get

|

(3.81) |

which can be rearranged to give

|

(3.82) |

Next: Rutherford Scattering Cross-Section

Up: Collisions

Previous: Boltzmann H-Theorem

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-23

![]() . This is the equation of a plane that passes through the origin, and whose normal is parallel

to the constant vector

. This is the equation of a plane that passes through the origin, and whose normal is parallel

to the constant vector ![]() . We, therefore, conclude that the relative position vector

. We, therefore, conclude that the relative position vector ![]() is constrained to lie in this plane,

which implies that the trajectories of both colliding particles are coplanar.

Let the plane

is constrained to lie in this plane,

which implies that the trajectories of both colliding particles are coplanar.

Let the plane

![]() coincide with the

coincide with the ![]() -

-![]() plane, so that we can write

plane, so that we can write

![]() . It is convenient to

define the standard plane polar coordinates

. It is convenient to

define the standard plane polar coordinates

![]() and

and

![]() .

When expressed in terms of these coordinates, the conserved angular momentum per unit mass becomes

.

When expressed in terms of these coordinates, the conserved angular momentum per unit mass becomes

![]() , where

, where

![]() and

and

![]() . It follows that

. It follows that

![$\displaystyle E = \frac{1}{2}\,\mu_{12}\,h^2\left[\left(\frac{dz}{d\theta}\right)^2 + z^2\right] + k\,z.$](img730.png)

![]() remains stationary at the origin,

remains stationary at the origin, ![]() ,

whereas particle

,

whereas particle ![]() traces out the path

traces out the path ![]() . Point

. Point ![]() corresponds to the closest approach of the

two particles. It follows, by symmetry (because Coulomb collisions are reversible), that the angles

corresponds to the closest approach of the

two particles. It follows, by symmetry (because Coulomb collisions are reversible), that the angles ![]() and

and ![]() shown in the figure are equal to one another. Hence, we deduce that

shown in the figure are equal to one another. Hence, we deduce that