|

(8.125) |

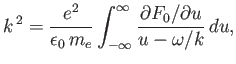

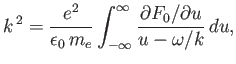

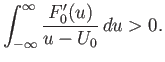

Consider the dispersion relation (8.23) for an electrostatic plasma wave in an unmagnetized quasi-neutral plasma with stationary ions. This relation can be written

|

(8.125) |

|

(8.127) |

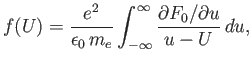

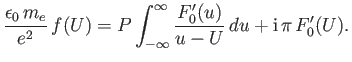

To answer the previous question, we employ a standard result in complex variable theory which states that

the number of zeros minus the number of poles of

![]() in a given region of the complex

in a given region of the complex ![]() plane

is

plane

is

![]() times the increase in the argument of

times the increase in the argument of

![]() as

as ![]() moves once counter-clockwise

around the boundary of this region (Flanigan 2010). To determine the latter quantity, we construct

what is known as a Nyquist diagram (Nyquist 1932). Because the region in which we are interested is the

upper-half complex plane, we let

moves once counter-clockwise

around the boundary of this region (Flanigan 2010). To determine the latter quantity, we construct

what is known as a Nyquist diagram (Nyquist 1932). Because the region in which we are interested is the

upper-half complex plane, we let ![]() follow the semi-circular path shown in Figure 8.10(a), and

plot the corresponding path followed in the complex plane by

follow the semi-circular path shown in Figure 8.10(a), and

plot the corresponding path followed in the complex plane by ![]() , as illustrated in Figure 8.10(b).

Now,

, as illustrated in Figure 8.10(b).

Now,

![]() as

as

![]() . Hence, if the radius of the semicircle in Figure 8.10(a)

tends to infinity, then only that part of the contour running along the real axis is important, and the

. Hence, if the radius of the semicircle in Figure 8.10(a)

tends to infinity, then only that part of the contour running along the real axis is important, and the ![]() contour

starts and finishes at the origin. Because the function

contour

starts and finishes at the origin. Because the function ![]() is analytic in the upper-half

is analytic in the upper-half ![]() plane, by virtue of the way

in which it is defined, the number of zeros of

plane, by virtue of the way

in which it is defined, the number of zeros of

![]() is equal to the change in argument (divided by

is equal to the change in argument (divided by ![]() ) of this

quantity as the path shown in Figure 8.10(b) is followed. However, this is just the number of times that the path

encircles the point

) of this

quantity as the path shown in Figure 8.10(b) is followed. However, this is just the number of times that the path

encircles the point ![]() . Hence, the criterion for instability is that the path should encircle part of the positive real axis.

Thus, in Figure 8.10(b), the system is unstable for the indicated values of

. Hence, the criterion for instability is that the path should encircle part of the positive real axis.

Thus, in Figure 8.10(b), the system is unstable for the indicated values of ![]() (Cairns 1985).

(Cairns 1985).

In an unstable system, there must exist a point such as ![]() in Figure 8.10(b) where the

in Figure 8.10(b) where the ![]() contour

crosses the real axis going from negative to positive imaginary part. Now, as

contour

crosses the real axis going from negative to positive imaginary part. Now, as

![]() moves along the real axis [cf., Equation (8.26)],

moves along the real axis [cf., Equation (8.26)],

|

(8.128) |

|

(8.129) |

The previous discussion implies that a single-humped velocity distribution function, such as a Maxwellian, is absolutely stable to

velocity-space instabilities (Gardner 1963). This follows because there is no finite value of ![]() at which such a distribution function

attains a minimum value. In fact, assuming that the distribution function,

at which such a distribution function

attains a minimum value. In fact, assuming that the distribution function, ![]() , is such that

, is such that

![]() as

as

![]() , we deduce that an unstable distribution function must possess at least

one minimum and two maxima for

, we deduce that an unstable distribution function must possess at least

one minimum and two maxima for ![]() in the range

in the range

![]() .

.