Next: Sommerfeld Precursor

Up: Wave Propagation in Uniform

Previous: Wave Propagation in Dispersive

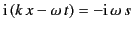

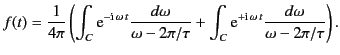

It is helpful to define

|

(871) |

Let us consider the two cases  and

and  separately.

separately.

Suppose that  . In this case, we distort the path

. In this case, we distort the path  , used to

evaluate the integral (870), into the path

, used to

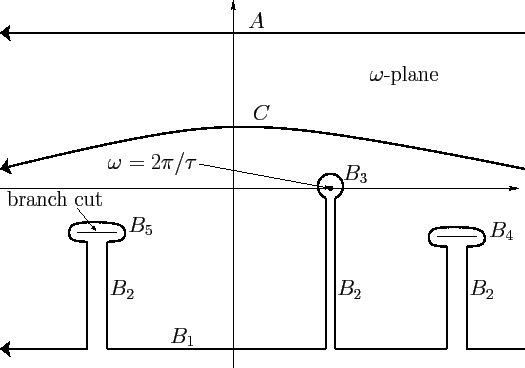

evaluate the integral (870), into the path  shown in Figure 8. This

is only a sensible thing to do if the real part of

shown in Figure 8. This

is only a sensible thing to do if the real part of

is negative at infinity in the upper half-plane. Now, it is clear from the

dispersion relation (871) that

is negative at infinity in the upper half-plane. Now, it is clear from the

dispersion relation (871) that

in the limit

in the limit

. Thus,

. Thus,

|

(872) |

It follows that

possesses a large negative real

part along path

possesses a large negative real

part along path  provided that

provided that  . Thus, Equation (870)

yields

. Thus, Equation (870)

yields

|

(873) |

for  . In other words, it is impossible for the wave-front

to propagate through the dispersive medium with a velocity greater than

the velocity of light in a vacuum.

. In other words, it is impossible for the wave-front

to propagate through the dispersive medium with a velocity greater than

the velocity of light in a vacuum.

Suppose that  . In this case, we distort the path

. In this case, we distort the path  into the

lower half-plane, because

into the

lower half-plane, because

has a negative real part at infinity in this region. In

doing this, the path becomes stuck not only at the singularity of the

denominator at

has a negative real part at infinity in this region. In

doing this, the path becomes stuck not only at the singularity of the

denominator at

, but also at the branch

points of the expression for

, but also at the branch

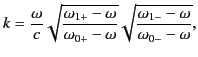

points of the expression for  . After a little algebra, the dispersion

relation (871) yields

. After a little algebra, the dispersion

relation (871) yields

|

(874) |

where

|

(875) |

and

|

(876) |

Here,

|

(877) |

is the plasma frequency, and

|

(878) |

parameterizes the damping.

In order to prevent multiple roots of Equation (875), it is necessary to

place branch cuts between

and

and

, and also

between

, and also

between

and

and

. (See Figure 8.)

. (See Figure 8.)

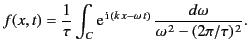

Figure 8:

Sketch of the integration contours used to evaluate Equation (870).

|

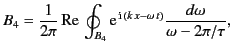

The path of integration  is conveniently split into the parts

is conveniently split into the parts

through

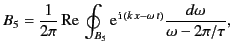

through  . (See Figure 8.) The contribution from

. (See Figure 8.) The contribution from  is negligible, because

the exponential in Equation (870) is vanishingly small on this part of

the integration path. Likewise, the contribution from

is negligible, because

the exponential in Equation (870) is vanishingly small on this part of

the integration path. Likewise, the contribution from  is zero,

because its two sections always cancel one another. The contribution

from

is zero,

because its two sections always cancel one another. The contribution

from  follows from the residue theorem:

follows from the residue theorem:

![$\displaystyle B_3 = \frac{1}{2\pi}\, {\rm Re} \left(2\pi\,{\rm i}\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}\,[k_\tau\, x- 2\pi\, t/\tau]}\right).$](img1827.png) |

(879) |

Here,  denotes the value of

denotes the value of  obtained from the dispersion relation

(871) in the limit

obtained from the dispersion relation

(871) in the limit

. Thus,

. Thus,

![$\displaystyle B_3 = {\rm e}^{-{\rm Im}(k_\tau)\, x} \sin\left[2\pi\,\frac{t}{\tau} -{\rm Re}(k_\tau)\,x\right].$](img1830.png) |

(880) |

In general, the contributions from  and

and  cannot be simplified

further. For the moment, we denote them as

cannot be simplified

further. For the moment, we denote them as

|

(881) |

and

|

(882) |

where the paths of integration circle the appropriate branch cuts.

Altogether, we have

![$\displaystyle f(x,t) = {\rm e}^{-{\rm Im}(k_\tau)\, x} \sin\left[2\pi\,\frac{t}{\tau} -{\rm Re}(k_\tau)\,x\right]+ B_4 + B_5$](img1834.png) |

(883) |

for  .

.

Let us now look at the special case  . For this value of

. For this value of  , we can change

the original path of integration to one at infinity in either the

upper or the lower half plane, because the integrand vanishes in each

case, through no longer exponentially, but rather as

, we can change

the original path of integration to one at infinity in either the

upper or the lower half plane, because the integrand vanishes in each

case, through no longer exponentially, but rather as

.

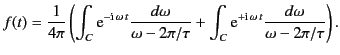

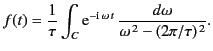

We can see this from Equation (867), which can be written in the form

.

We can see this from Equation (867), which can be written in the form

|

(884) |

Substitution of  for

for  in the second integral yields

in the second integral yields

|

(885) |

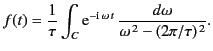

Now, applying dispersion theory, we obtain from the previous equation, just as we obtained

Equation (870) from Equation (867),

|

(886) |

Clearly, the integrand vanishes as

in the limit that

in the limit that

becomes very large. Thus, it vanishes as

becomes very large. Thus, it vanishes as

for

for  .

Because we can calculate

.

Because we can calculate  using either path

using either path  or path

or path  ,

we conclude that

,

we conclude that

![$\displaystyle f(x,t) = {\rm e}^{-{\rm Im}(k_\tau)\, x} \sin\!\left[2\pi\,\frac{t}{\tau} -{\rm Re}(k_\tau)\,x\right]+ B_4 + B_5 = 0$](img1844.png) |

(887) |

for  . Thus, there is continuity in the transition from the region

. Thus, there is continuity in the transition from the region

to the region

to the region  .

.

We are now in a position to make some meaningful statements regarding the

behavior of the signal at depth  within the dispersive medium.

Prior to the time

within the dispersive medium.

Prior to the time  , there is no wave motion. In other words, even if the phase velocity

is superluminal, no electromagnetic signal can arrive earlier than one propagating

at the velocity of light in vacuum,

, there is no wave motion. In other words, even if the phase velocity

is superluminal, no electromagnetic signal can arrive earlier than one propagating

at the velocity of light in vacuum,  . The wave motion

for

. The wave motion

for  is conveniently divided into two parts:

free oscillations and

forced oscillations. The former are given by

is conveniently divided into two parts:

free oscillations and

forced oscillations. The former are given by  ,

and the latter by

,

and the latter by

![$\displaystyle {\rm e}^{-{\rm Im}(k_\tau)\, x} \sin\!\left[2\pi\,\frac{t}{\tau} ...

...\tau)\, x} \sin\!\left( \frac{2\pi}{\tau}\left[t - \frac{x}{v_p}\right]\right),$](img1848.png) |

(888) |

where

|

(889) |

is termed the phase velocity. The forced oscillations have the

same sine wave characteristics and oscillation frequency as the incident

wave.

However, the wave amplitude is diminished by the damping coefficient, although,

as we have seen,

this is generally a negligible effect unless the frequency of the incident

wave closely matches one of the resonant frequencies of the dispersive

medium. The phase velocity  determines the velocity at which

a point of constant phase (e.g., a peak or trough) of the forced oscillation signal

propagates into the medium. However, the phase

velocity has no effect on the velocity

at which the forced oscillation wave-front propagates

into the medium. This latter velocity is equivalent to the velocity

of light in vacuum,

determines the velocity at which

a point of constant phase (e.g., a peak or trough) of the forced oscillation signal

propagates into the medium. However, the phase

velocity has no effect on the velocity

at which the forced oscillation wave-front propagates

into the medium. This latter velocity is equivalent to the velocity

of light in vacuum,  . The phase velocity

. The phase velocity

can be either greater or less than

can be either greater or less than

, in which case peaks and troughs either catch up with or fall further

behind the wave-front. Of course, peaks can never overtake the wave-front.

, in which case peaks and troughs either catch up with or fall further

behind the wave-front. Of course, peaks can never overtake the wave-front.

It is clear from Equations (876), (877), (882), and (883) that the free

oscillations oscillate with real frequencies that lie somewhere between

the resonant frequency,  , and the plasma frequency,

, and the plasma frequency,  .

Furthermore, the free oscillations are damped in time

like

.

Furthermore, the free oscillations are damped in time

like

. The free oscillations, like the

forced oscillations, begin at time

. The free oscillations, like the

forced oscillations, begin at time  . At

. At  , the free

and forced oscillations exactly cancel one another [see Equation (888)]. As

, the free

and forced oscillations exactly cancel one another [see Equation (888)]. As

increases, both the free and

forced oscillations set in, but the former rapidly damp away, leaving only

the forced oscillations. Thus, the free oscillations can be

regarded as

some sort of transient response of the medium to the incident

wave, whereas the forced oscillations determine the time asymptotic

response. The real frequency of the forced oscillations is that imposed

externally by the incident wave, whereas the real frequency of the free

oscillations is determined by the nature of the dispersive medium, quite

independently of the frequency of the incident wave.

increases, both the free and

forced oscillations set in, but the former rapidly damp away, leaving only

the forced oscillations. Thus, the free oscillations can be

regarded as

some sort of transient response of the medium to the incident

wave, whereas the forced oscillations determine the time asymptotic

response. The real frequency of the forced oscillations is that imposed

externally by the incident wave, whereas the real frequency of the free

oscillations is determined by the nature of the dispersive medium, quite

independently of the frequency of the incident wave.

One slightly surprising result of the previous analysis is the prediction that

the signal wave-front propagates into the dispersive medium

at the velocity of light in vacuum, irrespective of the

dispersive properties of the medium. Actually, this is a fairly

obvious result. As is well described by Feynman in his famous

Lectures on Physics, when an electromagnetic wave propagates through

a dispersive medium, the electrons and ions that make up

that medium oscillate in

sympathy with the incident wave, and, in doing so, emit radiation. The radiation from the electrons and ions, as well as the incident radiation,

travels at the velocity  . However, when these two radiation signals

are superposed, the net effect is as if the incident signal propagates through

the dispersive medium at a phase velocity that is different

from

. However, when these two radiation signals

are superposed, the net effect is as if the incident signal propagates through

the dispersive medium at a phase velocity that is different

from  . Consider the wave-front of the incident signal, which

clearly propagates

into the medium with the velocity

. Consider the wave-front of the incident signal, which

clearly propagates

into the medium with the velocity  . Prior to the arrival of this

wave-front, the electrons and ions are at rest, because no information regarding the

arrival of the incident wave at the surface of the medium can propagate faster than

. Prior to the arrival of this

wave-front, the electrons and ions are at rest, because no information regarding the

arrival of the incident wave at the surface of the medium can propagate faster than  .

After the arrival of the

wave-front, the electrons and ions are set into motion, and

emit radiation which affects the apparent phase velocity

of radiation that arrives somewhat later. But this radiation

certainly cannot affect the propagation velocity of the wave-front

itself, which has already passed by the time the electrons and ions

are set into motion (because of their finite inertia).

.

After the arrival of the

wave-front, the electrons and ions are set into motion, and

emit radiation which affects the apparent phase velocity

of radiation that arrives somewhat later. But this radiation

certainly cannot affect the propagation velocity of the wave-front

itself, which has already passed by the time the electrons and ions

are set into motion (because of their finite inertia).

Next: Sommerfeld Precursor

Up: Wave Propagation in Uniform

Previous: Wave Propagation in Dispersive

Richard Fitzpatrick

2014-06-27

![]() . In this case, we distort the path

. In this case, we distort the path ![]() , used to

evaluate the integral (870), into the path

, used to

evaluate the integral (870), into the path ![]() shown in Figure 8. This

is only a sensible thing to do if the real part of

shown in Figure 8. This

is only a sensible thing to do if the real part of

![]() is negative at infinity in the upper half-plane. Now, it is clear from the

dispersion relation (871) that

is negative at infinity in the upper half-plane. Now, it is clear from the

dispersion relation (871) that

![]() in the limit

in the limit

![]() . Thus,

. Thus,

![]() . In this case, we distort the path

. In this case, we distort the path ![]() into the

lower half-plane, because

into the

lower half-plane, because

![]() has a negative real part at infinity in this region. In

doing this, the path becomes stuck not only at the singularity of the

denominator at

has a negative real part at infinity in this region. In

doing this, the path becomes stuck not only at the singularity of the

denominator at

![]() , but also at the branch

points of the expression for

, but also at the branch

points of the expression for ![]() . After a little algebra, the dispersion

relation (871) yields

. After a little algebra, the dispersion

relation (871) yields

![]() is conveniently split into the parts

is conveniently split into the parts

![]() through

through ![]() . (See Figure 8.) The contribution from

. (See Figure 8.) The contribution from ![]() is negligible, because

the exponential in Equation (870) is vanishingly small on this part of

the integration path. Likewise, the contribution from

is negligible, because

the exponential in Equation (870) is vanishingly small on this part of

the integration path. Likewise, the contribution from ![]() is zero,

because its two sections always cancel one another. The contribution

from

is zero,

because its two sections always cancel one another. The contribution

from ![]() follows from the residue theorem:

follows from the residue theorem:

![$\displaystyle B_3 = \frac{1}{2\pi}\, {\rm Re} \left(2\pi\,{\rm i}\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}\,[k_\tau\, x- 2\pi\, t/\tau]}\right).$](img1827.png)

![]() . For this value of

. For this value of ![]() , we can change

the original path of integration to one at infinity in either the

upper or the lower half plane, because the integrand vanishes in each

case, through no longer exponentially, but rather as

, we can change

the original path of integration to one at infinity in either the

upper or the lower half plane, because the integrand vanishes in each

case, through no longer exponentially, but rather as

![]() .

We can see this from Equation (867), which can be written in the form

.

We can see this from Equation (867), which can be written in the form

![]() within the dispersive medium.

Prior to the time

within the dispersive medium.

Prior to the time ![]() , there is no wave motion. In other words, even if the phase velocity

is superluminal, no electromagnetic signal can arrive earlier than one propagating

at the velocity of light in vacuum,

, there is no wave motion. In other words, even if the phase velocity

is superluminal, no electromagnetic signal can arrive earlier than one propagating

at the velocity of light in vacuum, ![]() . The wave motion

for

. The wave motion

for ![]() is conveniently divided into two parts:

free oscillations and

forced oscillations. The former are given by

is conveniently divided into two parts:

free oscillations and

forced oscillations. The former are given by ![]() ,

and the latter by

,

and the latter by

![$\displaystyle {\rm e}^{-{\rm Im}(k_\tau)\, x} \sin\!\left[2\pi\,\frac{t}{\tau} ...

...\tau)\, x} \sin\!\left( \frac{2\pi}{\tau}\left[t - \frac{x}{v_p}\right]\right),$](img1848.png)

![]() , and the plasma frequency,

, and the plasma frequency, ![]() .

Furthermore, the free oscillations are damped in time

like

.

Furthermore, the free oscillations are damped in time

like

![]() . The free oscillations, like the

forced oscillations, begin at time

. The free oscillations, like the

forced oscillations, begin at time ![]() . At

. At ![]() , the free

and forced oscillations exactly cancel one another [see Equation (888)]. As

, the free

and forced oscillations exactly cancel one another [see Equation (888)]. As

![]() increases, both the free and

forced oscillations set in, but the former rapidly damp away, leaving only

the forced oscillations. Thus, the free oscillations can be

regarded as

some sort of transient response of the medium to the incident

wave, whereas the forced oscillations determine the time asymptotic

response. The real frequency of the forced oscillations is that imposed

externally by the incident wave, whereas the real frequency of the free

oscillations is determined by the nature of the dispersive medium, quite

independently of the frequency of the incident wave.

increases, both the free and

forced oscillations set in, but the former rapidly damp away, leaving only

the forced oscillations. Thus, the free oscillations can be

regarded as

some sort of transient response of the medium to the incident

wave, whereas the forced oscillations determine the time asymptotic

response. The real frequency of the forced oscillations is that imposed

externally by the incident wave, whereas the real frequency of the free

oscillations is determined by the nature of the dispersive medium, quite

independently of the frequency of the incident wave.

![]() . However, when these two radiation signals

are superposed, the net effect is as if the incident signal propagates through

the dispersive medium at a phase velocity that is different

from

. However, when these two radiation signals

are superposed, the net effect is as if the incident signal propagates through

the dispersive medium at a phase velocity that is different

from ![]() . Consider the wave-front of the incident signal, which

clearly propagates

into the medium with the velocity

. Consider the wave-front of the incident signal, which

clearly propagates

into the medium with the velocity ![]() . Prior to the arrival of this

wave-front, the electrons and ions are at rest, because no information regarding the

arrival of the incident wave at the surface of the medium can propagate faster than

. Prior to the arrival of this

wave-front, the electrons and ions are at rest, because no information regarding the

arrival of the incident wave at the surface of the medium can propagate faster than ![]() .

After the arrival of the

wave-front, the electrons and ions are set into motion, and

emit radiation which affects the apparent phase velocity

of radiation that arrives somewhat later. But this radiation

certainly cannot affect the propagation velocity of the wave-front

itself, which has already passed by the time the electrons and ions

are set into motion (because of their finite inertia).

.

After the arrival of the

wave-front, the electrons and ions are set into motion, and

emit radiation which affects the apparent phase velocity

of radiation that arrives somewhat later. But this radiation

certainly cannot affect the propagation velocity of the wave-front

itself, which has already passed by the time the electrons and ions

are set into motion (because of their finite inertia).