Next: Simple harmonic motion Up: Newtonian mechanics Previous: Non-isolated systems

moving in the

moving in the  -direction, say,

under the action of some

-direction, say,

under the action of some  -directed force

-directed force  .

Suppose that

.

Suppose that  is a conservative force, such as gravity. In this case,

according to Equation (2.19), we can write

where

is a conservative force, such as gravity. In this case,

according to Equation (2.19), we can write

where  is the potential energy of the particle at position

is the potential energy of the particle at position  .

.

Let the curve  take the form shown in Figure 2.4.

For instance, this curve might represent the gravitational potential energy

of a cyclist freewheeling in a hilly region. Observe that we have set the

potential energy at infinity to zero (which we are generally

free to do, because

potential energy is undefined to an arbitrary additive constant). This is a fairly common convention.

What can we deduce about the motion of the particle in this potential?

take the form shown in Figure 2.4.

For instance, this curve might represent the gravitational potential energy

of a cyclist freewheeling in a hilly region. Observe that we have set the

potential energy at infinity to zero (which we are generally

free to do, because

potential energy is undefined to an arbitrary additive constant). This is a fairly common convention.

What can we deduce about the motion of the particle in this potential?

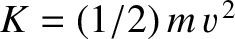

Well, we know that the total energy,  —which is the sum of the kinetic

energy,

—which is the sum of the kinetic

energy,  , and the potential energy,

, and the potential energy,  —is a constant of the motion. [See Equation (2.22).]

Hence, we can write

—is a constant of the motion. [See Equation (2.22).]

Hence, we can write

, and neither

, and neither

nor

nor

can be negative. Hence, the preceding

expression tells us that the particle's motion is restricted to the

region (or regions) in which the potential energy curve

can be negative. Hence, the preceding

expression tells us that the particle's motion is restricted to the

region (or regions) in which the potential energy curve  falls

below the value

falls

below the value  . This idea is illustrated in Figure 2.4.

Suppose that the total energy of the system is

. This idea is illustrated in Figure 2.4.

Suppose that the total energy of the system is  . It is clear, from

the figure, that the particle is trapped inside one or other of the two dips

in the potential; these dips are

generally referred to as potential wells.

Suppose that we now raise the energy to

. It is clear, from

the figure, that the particle is trapped inside one or other of the two dips

in the potential; these dips are

generally referred to as potential wells.

Suppose that we now raise the energy to  . In this

case, the particle is free to enter or leave each of the potential wells, but

its motion is still bounded to some extent, because it clearly cannot move off to

infinity. Finally, let us raise the energy to

. In this

case, the particle is free to enter or leave each of the potential wells, but

its motion is still bounded to some extent, because it clearly cannot move off to

infinity. Finally, let us raise the energy to  . Now the

particle is unbounded; that is, it can move off to infinity. In conservative systems

in which it makes sense to adopt the convention that the potential

energy at infinity is zero, bounded systems are characterized

by

. Now the

particle is unbounded; that is, it can move off to infinity. In conservative systems

in which it makes sense to adopt the convention that the potential

energy at infinity is zero, bounded systems are characterized

by  , whereas unbounded systems are characterized by

, whereas unbounded systems are characterized by  .

.

The preceding discussion suggests that the motion of a particle moving in a potential

generally becomes less bounded as the total energy  of the system increases.

Conversely, we would expect the motion to become more bounded as

of the system increases.

Conversely, we would expect the motion to become more bounded as  decreases.

In fact, if the energy becomes sufficiently small then it appears likely that the

system will settle down in some equilibrium state in which the particle remains stationary.

Let us try to identify any prospective equilibrium states in Figure 2.4.

If the particle remains stationary then it must be subject to zero force (otherwise,

it would accelerate). Hence, according to Equation (2.45), an equilibrium

state is characterized by

decreases.

In fact, if the energy becomes sufficiently small then it appears likely that the

system will settle down in some equilibrium state in which the particle remains stationary.

Let us try to identify any prospective equilibrium states in Figure 2.4.

If the particle remains stationary then it must be subject to zero force (otherwise,

it would accelerate). Hence, according to Equation (2.45), an equilibrium

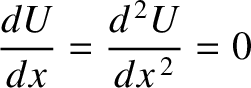

state is characterized by

|

(2.47) |

. It can

be seen that the

. It can

be seen that the  curve shown in Figure 2.4 has

three associated equilibrium states located at

curve shown in Figure 2.4 has

three associated equilibrium states located at

,

,  , and

, and  .

.

Let us now make a distinction between stable equilibrium points

and unstable equilibrium points. When the particle is slightly

displaced from a stable equilibrium point then the resultant force acting

on it

must always be such as to return it to this point.

In other words, if  is an equilibrium point then we require

is an equilibrium point then we require

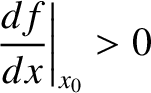

|

(2.48) |

,

then the force must act to the left, so that

,

then the force must act to the left, so that  , and vice versa.

Likewise, if

, and vice versa.

Likewise, if

|

(2.49) |

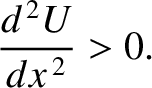

is unstable. It follows, from

Equation (2.45), that stable equilibrium points are

characterized by

is unstable. It follows, from

Equation (2.45), that stable equilibrium points are

characterized by

|

(2.50) |

. Likewise, an unstable

equilibrium point corresponds to a maximum of the

. Likewise, an unstable

equilibrium point corresponds to a maximum of the  curve. Hence,

we conclude that,

in Figure 2.4,

curve. Hence,

we conclude that,

in Figure 2.4,  and

and  are stable equilibrium points, whereas

are stable equilibrium points, whereas  is an unstable equilibrium point.

Of course, this makes perfect sense if we think of

is an unstable equilibrium point.

Of course, this makes perfect sense if we think of  as

a gravitational potential energy curve, so that

as

a gravitational potential energy curve, so that  is

directly proportional to height. In this case, all we are saying is that it is

easy to confine a low energy mass at the bottom of a smooth valley,

but it is very difficult to balance the same mass on the top of

a smooth hill (because any slight displacement of the mass will cause it

to slide down the hill). Finally, if

is

directly proportional to height. In this case, all we are saying is that it is

easy to confine a low energy mass at the bottom of a smooth valley,

but it is very difficult to balance the same mass on the top of

a smooth hill (because any slight displacement of the mass will cause it

to slide down the hill). Finally, if

|

(2.51) |

curve. See Figure 2.5.

curve. See Figure 2.5.

The equation of motion of a particle moving in one dimension

under the action of a conservative force is, in principle, integrable. Because

, the energy

conservation equation, Equation (2.46), can be rearranged to give

, the energy

conservation equation, Equation (2.46), can be rearranged to give

![$\displaystyle \varv = \pm\left(\frac{2\,[E-U(x)]}{m}\right)^{1/2},$](img215.png) |

(2.52) |

signs correspond to motion to the left and to the right, respectively. However, because

signs correspond to motion to the left and to the right, respectively. However, because

, this expression can be integrated to give

where

, this expression can be integrated to give

where

. For sufficiently simple potential functions,

. For sufficiently simple potential functions,  , Equation (2.53) can be solved to give

, Equation (2.53) can be solved to give  as a function of

as a function of  .

For instance, if

.

For instance, if

,

,  , and the plus sign is chosen, then

, and the plus sign is chosen, then

![$\displaystyle t = \left(\frac{m}{k}\right)^{1/2}\int_0^{(k/2\,E)^{1/2}\,x}\frac...

...c{m}{k}\right)^{1/2} \sin^{-1}\left[\left(\frac{k}{2\,E}\right)^{1/2} x\right],$](img222.png) |

(2.54) |

|

(2.55) |

and

and

.

Note that the particle reverses direction each time it reaches one of the so-called

turning points (

.

Note that the particle reverses direction each time it reaches one of the so-called

turning points ( ) at which

) at which  (and, so,

(and, so,  ).

).