Next: Newton's third law of Up: Newtonian mechanics Previous: Newton's first law of

, then its equation of motion

is given by

where the momentum,

, then its equation of motion

is given by

where the momentum,  , is the product of the object's inertial

mass,

, is the product of the object's inertial

mass,  , and its velocity,

, and its velocity,  . If

. If  is not a function of time then Equation (2.13) reduces to the

familiar equation

Note that this equation is only valid in a inertial frame.

Clearly, the inertial mass of an object measures its reluctance to deviate

from its preferred state of uniform motion in a straight line (in an

inertial frame). Of course, the preceding equation of motion can only be solved if we have an independent expression for the force,

is not a function of time then Equation (2.13) reduces to the

familiar equation

Note that this equation is only valid in a inertial frame.

Clearly, the inertial mass of an object measures its reluctance to deviate

from its preferred state of uniform motion in a straight line (in an

inertial frame). Of course, the preceding equation of motion can only be solved if we have an independent expression for the force,  (i.e., a law of force).

Let us suppose that this is the case.

(i.e., a law of force).

Let us suppose that this is the case.

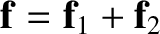

An important corollary of Newton's second law is that force is a vector

quantity. This must be the case, because the law equates force to the

product of a scalar (mass) and a vector (acceleration).2.2

Note that acceleration is obviously a vector because it is directly related to displacement, which is the prototype of all vectors. One consequence of force being a vector is

that two forces,  and

and  , both acting at a given

point, have the same effect as a single force,

, both acting at a given

point, have the same effect as a single force,

,

acting at the same point, where the summation is performed according to the

laws of vector addition. Likewise, a single force,

,

acting at the same point, where the summation is performed according to the

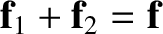

laws of vector addition. Likewise, a single force,  , acting at

a given point, has the same effect as two forces,

, acting at

a given point, has the same effect as two forces,  and

and  ,

acting at the same point, provided that

,

acting at the same point, provided that

. This

method of combining and splitting forces is known as the resolution of

forces; it lies at the heart of many calculations in Newtonian mechanics.

. This

method of combining and splitting forces is known as the resolution of

forces; it lies at the heart of many calculations in Newtonian mechanics.

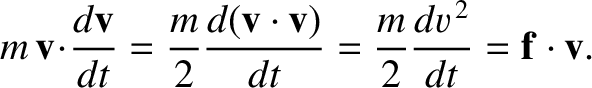

Taking the scalar product of Equation (2.14) with the velocity,  ,

we obtain

,

we obtain

|

(2.15) |

|

(2.17) |

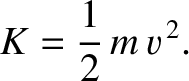

represents the energy that the object possesses by virtue of its motion.

This type of energy is generally known as kinetic energy. Thus, Equation (2.16) states that any work done on point object by an external force

goes to increase the object's kinetic energy.

represents the energy that the object possesses by virtue of its motion.

This type of energy is generally known as kinetic energy. Thus, Equation (2.16) states that any work done on point object by an external force

goes to increase the object's kinetic energy.

Suppose that, under the action of the force,  , our object moves

from point

, our object moves

from point  at time

at time  to point

to point  at time

at time  . The

net change in the object's kinetic energy is obtained by integrating

Equation (2.16):

. The

net change in the object's kinetic energy is obtained by integrating

Equation (2.16):

.

Here,

.

Here,  is an element of the object's path between points

is an element of the object's path between points  and

and  , and the integral in

, and the integral in  represents the net work done by the

force as the object moves along the path from

represents the net work done by the

force as the object moves along the path from  to

to  .

.

As is well known, there are basically two kinds

of forces in nature: first, those for which line integrals of the type

depend on the end points, but not

on the path taken between these points; second, those for which

line integrals of the type

depend on the end points, but not

on the path taken between these points; second, those for which

line integrals of the type

depend

both on the end points, and the path taken between these points.

The first kind of force is termed conservative, whereas the

second kind is termed non-conservative. It can be

demonstrated that if the line integral

depend

both on the end points, and the path taken between these points.

The first kind of force is termed conservative, whereas the

second kind is termed non-conservative. It can be

demonstrated that if the line integral

is path-independent, for all

choices of

is path-independent, for all

choices of  and

and  , then the force

, then the force  can

be written as the gradient of a scalar field. (See Section A.5.) In other words, all

conservative forces satisfy

can

be written as the gradient of a scalar field. (See Section A.5.) In other words, all

conservative forces satisfy

. [Incidentally, mathematicians, as opposed to physicists and astronomers, usually

write

. [Incidentally, mathematicians, as opposed to physicists and astronomers, usually

write

.]

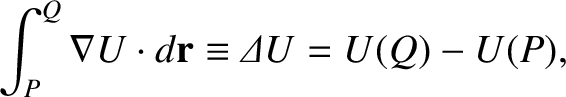

Note that

.]

Note that

|

(2.20) |

and

and  .

Hence, it follows from Equation (2.18)

that

.

Hence, it follows from Equation (2.18)

that

|

(2.21) |

is the object's total energy, which is conserved;

is the object's total energy, which is conserved;  is the energy the

object has by virtue of its motion, otherwise known as its

kinetic energy; and

is the energy the

object has by virtue of its motion, otherwise known as its

kinetic energy; and  is the energy the object has by

virtue of its position, otherwise known as its potential

energy. Note, however, that we can write energy conservation

equations only for conservative forces. Gravity is an obvious example of such a force.

Incidentally, potential energy is undefined to an arbitrary additive constant.

In fact, it is only the difference in potential energy between

different points in space that is well defined.

is the energy the object has by

virtue of its position, otherwise known as its potential

energy. Note, however, that we can write energy conservation

equations only for conservative forces. Gravity is an obvious example of such a force.

Incidentally, potential energy is undefined to an arbitrary additive constant.

In fact, it is only the difference in potential energy between

different points in space that is well defined.