Next: Coriolis force Up: Rotating reference frames Previous: Rotating reference frames

, on the Earth's surface. See Figure 6.1.

The latter reference frame thus rotates with respect to the former (about an

axis passing through the Earth's center)

with an angular velocity vector,

, on the Earth's surface. See Figure 6.1.

The latter reference frame thus rotates with respect to the former (about an

axis passing through the Earth's center)

with an angular velocity vector,

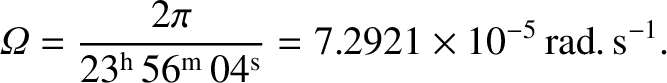

, which points from the center of the Earth toward its north pole and is of magnitude

, which points from the center of the Earth toward its north pole and is of magnitude

|

(6.10) |

is the length of a sidereal day; that is, the Earth's rotation

period relative to the distant stars (Yoder 1995).6.1

is the length of a sidereal day; that is, the Earth's rotation

period relative to the distant stars (Yoder 1995).6.1

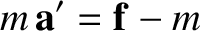

Consider an object that appears stationary in our rotating reference frame; that is, an object that is stationary with respect to the Earth's surface. According to Equation (6.9), the object's apparent equation of motion in the rotating frame takes the form

|

(6.11) |

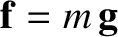

. Here, the local gravitational acceleration,

. Here, the local gravitational acceleration,  ,

points directly toward the center of the Earth. It follows

that the apparent gravitational acceleration in the rotating frame is written

where

,

points directly toward the center of the Earth. It follows

that the apparent gravitational acceleration in the rotating frame is written

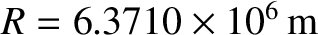

where  is the displacement vector of the origin of the rotating

frame (which lies on the Earth's surface) with respect to

the center of the Earth. Here, we are assuming that our object is situated

relatively close to the Earth's surface (i.e.,

is the displacement vector of the origin of the rotating

frame (which lies on the Earth's surface) with respect to

the center of the Earth. Here, we are assuming that our object is situated

relatively close to the Earth's surface (i.e.,

).

).

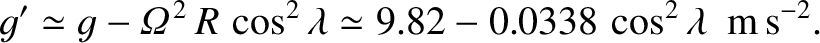

It can be seen from Equation (6.12) that the apparent gravitational acceleration

of a stationary object close to the Earth's surface has two components: first,

the true gravitational acceleration,  , of magnitude

, of magnitude

, which always points directly toward the

center of the Earth (Yoder 1995); and, second, the so-called centrifugal acceleration,

, which always points directly toward the

center of the Earth (Yoder 1995); and, second, the so-called centrifugal acceleration,

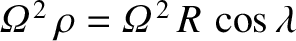

. The latter acceleration is normal to the Earth's axis of

rotation, and always points directly away from this axis. The magnitude

of the centrifugal acceleration is

. The latter acceleration is normal to the Earth's axis of

rotation, and always points directly away from this axis. The magnitude

of the centrifugal acceleration is

, where

, where

is the perpendicular distance to the Earth's rotation axis, and

is the perpendicular distance to the Earth's rotation axis, and

is the Earth's radius (Yoder 1995). See Figure 6.2.

is the Earth's radius (Yoder 1995). See Figure 6.2.

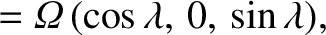

It is convenient to define Cartesian axes in the rotating reference frame such that the  -axis

points vertically upward and

-axis

points vertically upward and  - and

- and  -axes are horizontal, with

the

-axes are horizontal, with

the  -axis pointing directly northward and the

-axis pointing directly northward and the  -axis pointing directly westward. See Figure 6.1.

The Cartesian components of the Earth's angular velocity are thus

-axis pointing directly westward. See Figure 6.1.

The Cartesian components of the Earth's angular velocity are thus

|

(6.13) |

and

and  are written

are written

|

|

(6.14) |

|

|

(6.15) |

|

(6.17) |

percent, being largest

at the poles, and smallest at the equator. This variation in apparent

gravitational acceleration, due (ultimately) to the Earth's rotation, causes the

Earth itself to bulge slightly at the equator (see Section 6.5), which has the effect of further intensifying the variation (see Section 6.9, Exercise 6), because a point on the surface of the Earth at the

equator is slightly further away from the Earth's center than a similar point at one of the

poles (and, hence, the true gravitational acceleration is slightly weaker in the

former case).

percent, being largest

at the poles, and smallest at the equator. This variation in apparent

gravitational acceleration, due (ultimately) to the Earth's rotation, causes the

Earth itself to bulge slightly at the equator (see Section 6.5), which has the effect of further intensifying the variation (see Section 6.9, Exercise 6), because a point on the surface of the Earth at the

equator is slightly further away from the Earth's center than a similar point at one of the

poles (and, hence, the true gravitational acceleration is slightly weaker in the

former case).

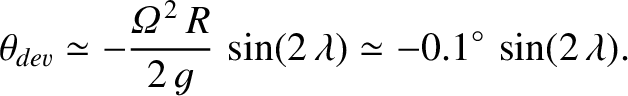

Another consequence of centrifugal acceleration is that the apparent gravitational acceleration on the Earth's surface has a horizontal component aligned in the north/south direction. This horizontal component ensures that the apparent gravitational acceleration does not point directly toward the center of the Earth. In other words, a plumb-line on the surface of the Earth does not point vertically downward (toward the center of the Earth), but is deflected slightly away from a true vertical in the north/south direction. The angular deviation from true vertical can easily be calculated from Equation (6.16):

|

(6.18) |

) and northward in the southern hemisphere (i.e.,

) and northward in the southern hemisphere (i.e.,

). The deflection is

zero at the poles and at the equator, and it reaches its maximum magnitude

(which is very small) at middle latitudes.

). The deflection is

zero at the poles and at the equator, and it reaches its maximum magnitude

(which is very small) at middle latitudes.