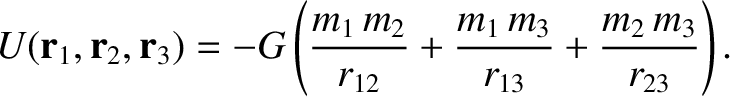

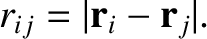

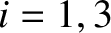

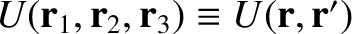

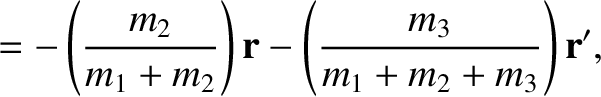

Consider the Earth–Moon–Sun system. See Figure 11.1. Let the  , for

, for  , denote the masses of the Earth, the

Moon, and the Sun, respectively. Furthermore, let the

, denote the masses of the Earth, the

Moon, and the Sun, respectively. Furthermore, let the  , for

, for  , denote the position vectors of the Earth, the Moon, and the

Sun, respectively, in a non-rotating reference frame in which the Earth–Moon–Sun barycenter,

, denote the position vectors of the Earth, the Moon, and the

Sun, respectively, in a non-rotating reference frame in which the Earth–Moon–Sun barycenter,  , is at rest at the origin. The equations of motion of the three bodies that

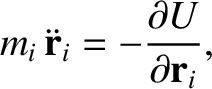

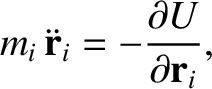

make up the Earth–Moon–Sun system can be written

, is at rest at the origin. The equations of motion of the three bodies that

make up the Earth–Moon–Sun system can be written

|

(11.1) |

for  , where

, where

|

(11.2) |

(See Chapter 4.) Here,

|

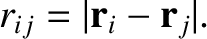

(11.3) |

Furthermore,

|

(11.4) |

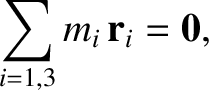

because the barycenter of the Earth–Moon–Sun system lies at the origin.

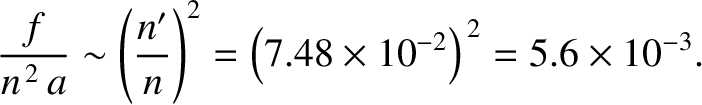

Figure: 11.1

The Earth–Moon–Sun system. Here,  denotes the Earth,

denotes the Earth,  the Moon, and

the Moon, and  the Sun. Furthermore,

the Sun. Furthermore,  is the

barycenter of the Earth–Moon–Sun system, whereas

is the

barycenter of the Earth–Moon–Sun system, whereas  is the barycenter of the Earth–Moon system.

is the barycenter of the Earth–Moon system.

|

|

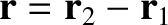

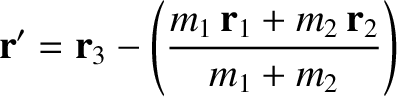

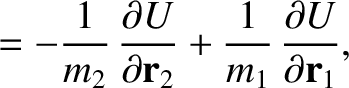

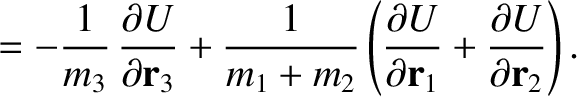

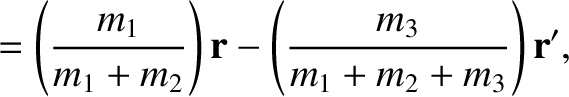

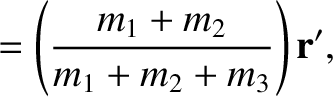

Let

|

(11.5) |

be the position vector of the Moon relative to the Earth, and let

|

(11.6) |

be the position vector of the Sun relative to the Earth–Moon barycenter,  . It follows that

Now, assuming that

. It follows that

Now, assuming that

,

we can write

,

we can write

|

(11.9) |

We conclude that

so that

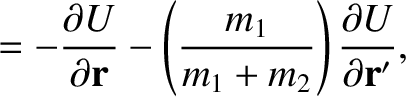

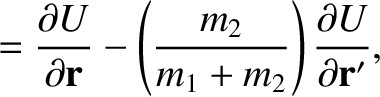

Equations (11.4)–(11.6) yield

which implies that

Let

|

(11.21) |

It follows from Equations (11.18)–(11.20) that

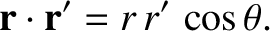

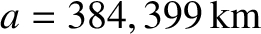

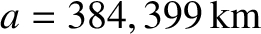

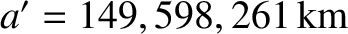

Note that

, where

, where

and

and

are the

major radii of the lunar orbit about the Earth, and the orbit of the Earth-Moon barycenter about the Sun, respectively (Yoder 1995).

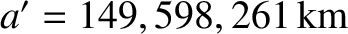

Now,

are the

major radii of the lunar orbit about the Earth, and the orbit of the Earth-Moon barycenter about the Sun, respectively (Yoder 1995).

Now,

|

(11.25) |

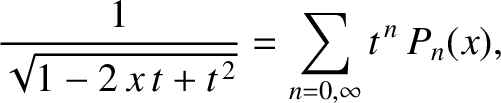

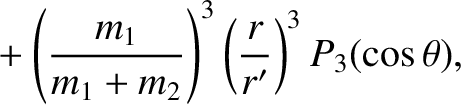

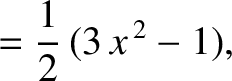

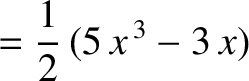

for  and

and  , where the

, where the  are Legendre polynomials (Abramowitz and Stegun 1965b).

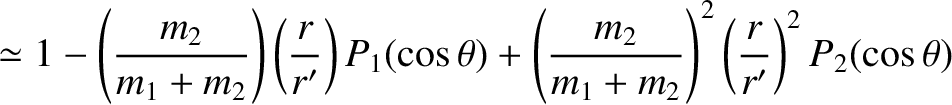

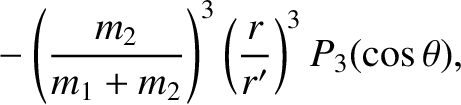

Thus, expanding Equations (11.23) and (11.24) to third order in the small parameters

are Legendre polynomials (Abramowitz and Stegun 1965b).

Thus, expanding Equations (11.23) and (11.24) to third order in the small parameters

![$[m_2/(m_1+m_2)]\,(r/r)'$](img2998.png) and

and

![$[m_1/(m_1+m_2)]\,(r/r)'$](img2999.png) , respectively, we obtain

respectively.

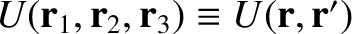

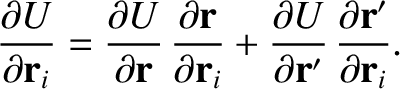

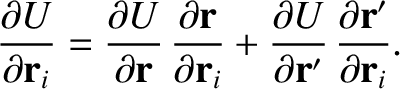

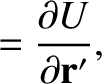

It follows from Equation (11.2) that

where use has been made of

(Abramowitz and Stegun 1965b),

as well as Equation (11.21).

, respectively, we obtain

respectively.

It follows from Equation (11.2) that

where use has been made of

(Abramowitz and Stegun 1965b),

as well as Equation (11.21).

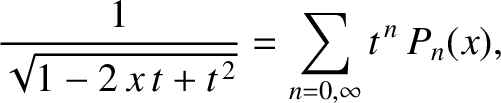

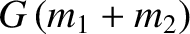

Let (see Chapter 4)

where

per day is the mean orbital angular velocity of the Moon around the Earth, and

per day is the mean orbital angular velocity of the Moon around the Earth, and

per day

is the mean orbital angular velocity of the Earth–Moon barycenter around the Sun (Yoder 1995). Here, we have neglected the combined mass of the

Earth and the Moon,

per day

is the mean orbital angular velocity of the Earth–Moon barycenter around the Sun (Yoder 1995). Here, we have neglected the combined mass of the

Earth and the Moon,  , with respect to the mass of the Sun,

, with respect to the mass of the Sun,  , because

, because

(Yoder 1995).

It follows from Equations (11.13), (11.14), and (11.28) that the equations of motion of the

Moon and the Earth–Moon barycenter can be written

respectively, where

(Yoder 1995).

It follows from Equations (11.13), (11.14), and (11.28) that the equations of motion of the

Moon and the Earth–Moon barycenter can be written

respectively, where

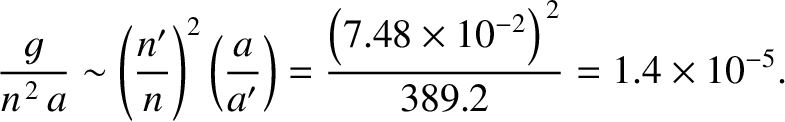

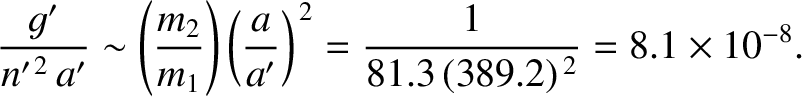

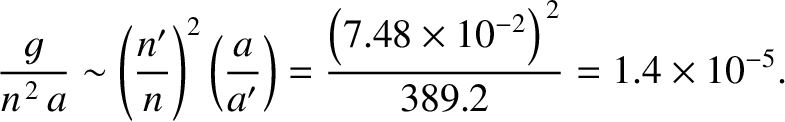

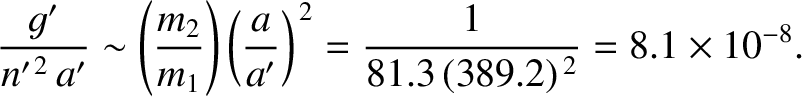

According to Equations (11.33) and (11.35), the relative size of the lowest-order (quadrupole) solar disturbance of the lunar orbit is

|

(11.38) |

On the other hand, according to Equation (11.36), the relative size of the next-order (octupole) solar disturbance of the lunar

orbit is

|

(11.39) |

Finally, according to Equations (11.34) and (11.37), the relative size of the lowest-order (octupole) disturbance of the orbit of the

Earth–Moon barycenter around the Sun, due to the combined effect of the Earth and the Moon, is

|

(11.40) |

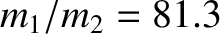

Here, use has been made of the fact that the ratio of the terrestrial to the lunar mass is

(Yoder 1995). Clearly, it is an excellent approximation

to neglect the octupole disturbance of the orbit of the Earth–Moon barycenter around the Sun, while retaining the quadrupole and octupole disturbances of the

orbit of the Moon around the Earth. Adopting this approximation, we conclude that the former orbit is an unperturbed Keplerian ellipse.

(Yoder 1995). Clearly, it is an excellent approximation

to neglect the octupole disturbance of the orbit of the Earth–Moon barycenter around the Sun, while retaining the quadrupole and octupole disturbances of the

orbit of the Moon around the Earth. Adopting this approximation, we conclude that the former orbit is an unperturbed Keplerian ellipse.

One obvious way of proceeding would be to express the right-hand side of the lunar equation of motion, Equation (11.33), as the gradient

of a disturbing function (see Section 11.18, Exercise 1), and then to use this function to determine the time evolution of the Moon's osculating orbital

elements from Lagrange's planetary equations. (See Chapter 10.) Unfortunately, this approach is fraught with mathematical difficulties. (See Brouwer and Clemence 1961). It is actually more straightforward to directly solve Equation (11.33) in a Cartesian coordinate system. This method of solution is

outlined below.

, for

, for  , denote the masses of the Earth, the

Moon, and the Sun, respectively. Furthermore, let the

, denote the masses of the Earth, the

Moon, and the Sun, respectively. Furthermore, let the  , for

, for  , denote the position vectors of the Earth, the Moon, and the

Sun, respectively, in a non-rotating reference frame in which the Earth–Moon–Sun barycenter,

, denote the position vectors of the Earth, the Moon, and the

Sun, respectively, in a non-rotating reference frame in which the Earth–Moon–Sun barycenter,  , is at rest at the origin. The equations of motion of the three bodies that

make up the Earth–Moon–Sun system can be written

, is at rest at the origin. The equations of motion of the three bodies that

make up the Earth–Moon–Sun system can be written

, where

(See Chapter 4.) Here,

, where

(See Chapter 4.) Here,

![\includegraphics[height=2.5in]{Chapter10/fig10_1.eps}](img2958.png)

. It follows that

. It follows that

,

we can write

,

we can write

, where

, where

and

and

are the

major radii of the lunar orbit about the Earth, and the orbit of the Earth-Moon barycenter about the Sun, respectively (Yoder 1995).

Now,

are the

major radii of the lunar orbit about the Earth, and the orbit of the Earth-Moon barycenter about the Sun, respectively (Yoder 1995).

Now,

and

and  , where the

, where the  are Legendre polynomials (Abramowitz and Stegun 1965b).

Thus, expanding Equations (11.23) and (11.24) to third order in the small parameters

are Legendre polynomials (Abramowitz and Stegun 1965b).

Thus, expanding Equations (11.23) and (11.24) to third order in the small parameters

![$[m_2/(m_1+m_2)]\,(r/r)'$](img2998.png) and

and

![$[m_1/(m_1+m_2)]\,(r/r)'$](img2999.png) , respectively, we obtain

, respectively, we obtain

per day is the mean orbital angular velocity of the Moon around the Earth, and

per day is the mean orbital angular velocity of the Moon around the Earth, and

per day

is the mean orbital angular velocity of the Earth–Moon barycenter around the Sun (Yoder 1995). Here, we have neglected the combined mass of the

Earth and the Moon,

per day

is the mean orbital angular velocity of the Earth–Moon barycenter around the Sun (Yoder 1995). Here, we have neglected the combined mass of the

Earth and the Moon,  , with respect to the mass of the Sun,

, with respect to the mass of the Sun,  , because

, because

(Yoder 1995).

It follows from Equations (11.13), (11.14), and (11.28) that the equations of motion of the

Moon and the Earth–Moon barycenter can be written

respectively, where

(Yoder 1995).

It follows from Equations (11.13), (11.14), and (11.28) that the equations of motion of the

Moon and the Earth–Moon barycenter can be written

respectively, where

(Yoder 1995). Clearly, it is an excellent approximation

to neglect the octupole disturbance of the orbit of the Earth–Moon barycenter around the Sun, while retaining the quadrupole and octupole disturbances of the

orbit of the Moon around the Earth. Adopting this approximation, we conclude that the former orbit is an unperturbed Keplerian ellipse.

(Yoder 1995). Clearly, it is an excellent approximation

to neglect the octupole disturbance of the orbit of the Earth–Moon barycenter around the Sun, while retaining the quadrupole and octupole disturbances of the

orbit of the Moon around the Earth. Adopting this approximation, we conclude that the former orbit is an unperturbed Keplerian ellipse.