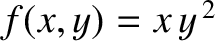

Consider a two-dimensional function  that is defined for all

that is defined for all  and

and  .

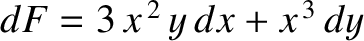

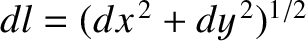

What is meant by the integral of

.

What is meant by the integral of  along a given curve joining the points

along a given curve joining the points  and

and  in the

in the  -

- plane?

Well, we first draw out

plane?

Well, we first draw out  as a function of length

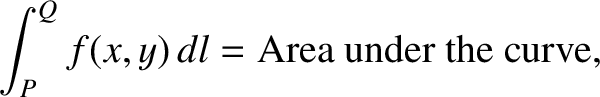

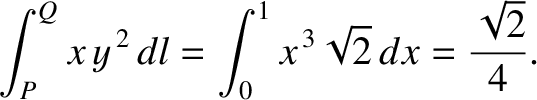

as a function of length  along the path. See Figure A.13. The integral is then simply given

by

along the path. See Figure A.13. The integral is then simply given

by

|

(1.69) |

where

.

.

Figure A.13:

A line integral.

|

|

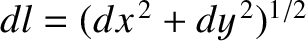

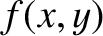

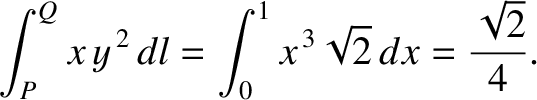

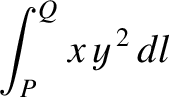

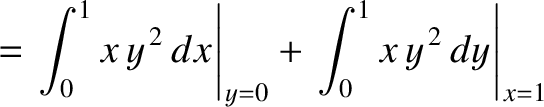

As an example of this, consider the integral of

between

between  and

and  along the

two routes indicated in Figure A.14.

Along route 1 we have

along the

two routes indicated in Figure A.14.

Along route 1 we have  , so

, so

. Thus,

. Thus,

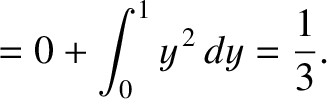

|

(1.70) |

The integration along route 2 gives

Note that the integral depends on the route taken between the initial and final points.

Figure A.14:

An example line integral.

|

|

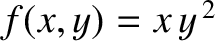

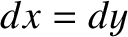

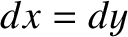

The most common type of line integral is one in which the contributions from  and

and  are evaluated

separately, rather that through the path length

are evaluated

separately, rather that through the path length  ; that is,

; that is,

![$\displaystyle \int_P^Q \left[ f(x,y)\,dx + g(x,y)\,dy\right].$](img4702.png) |

(1.72) |

As an example of this, consider the integral

![$\displaystyle \int_P^Q \left[ y\,dx + x^{\,3}\,dy\right]$](img4703.png) |

(1.73) |

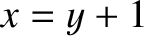

along the two routes indicated in Figure A.15.

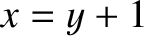

Along route 1 we have  and

and  , so

, so

![$\displaystyle \int_P^Q \left[ y\,dx + x^{\,3}\,dy\right]= \int_{0}^1\left[y\,dy + (y+1)^3\,dy\right] = \frac{17}{4}.$](img4706.png) |

(1.74) |

Along route 2,

![$\displaystyle \int_P^Q \left[ y\,dx + x^{\,3}\,dy\right]= \left.\int_0^1 x^{\,3}\,dy\right\vert _{x=1} + \left.\int_1^2 y\,dx\right\vert _{y=1} = \frac{7}{4}.$](img4707.png) |

(1.75) |

Again, the integral depends on the path of integration.

Figure A.15:

An example line integral.

|

|

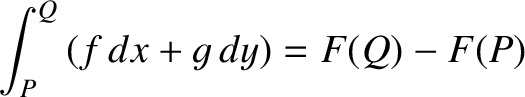

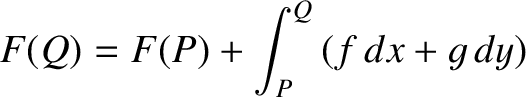

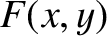

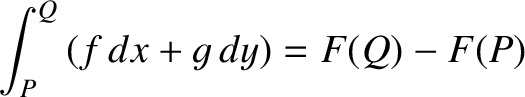

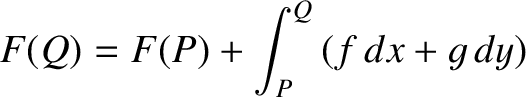

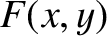

Suppose that we have a line integral that does not depend on the path of integration. It

follows that

|

(1.76) |

for some function  . Given

. Given  for one point

for one point  in the

in the  -

- plane, then

plane, then

|

(1.77) |

defines  for all other points in the plane. We can then draw a contour map of

for all other points in the plane. We can then draw a contour map of  .

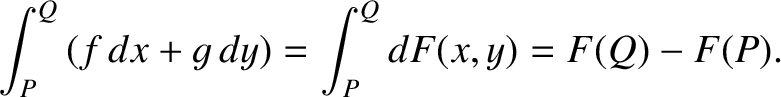

The line integral between points

.

The line integral between points  and

and  is simply the change in height in the contour

map between these two points:

is simply the change in height in the contour

map between these two points:

|

(1.78) |

Thus,

|

(1.79) |

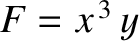

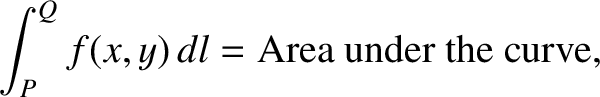

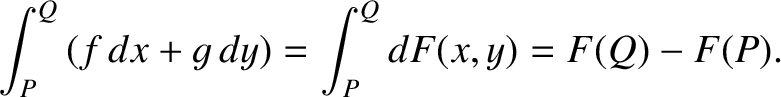

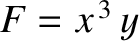

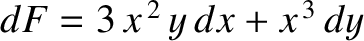

For instance, if

then

then

and

and

![$\displaystyle \int_P^Q \left(3\,x^{\,2}\,y\,dx + x^{\,3}\,dy\right) = \left[x^{\,3}\,y\right]_P^Q$](img4718.png) |

(1.80) |

is independent of the path of integration.

It is clear that there are two distinct types of line integral. Those that depend only on their

endpoints and not on the path of integration, and those that depend both on their endpoints

and the integration path. Later on, we shall learn how to distinguish between these two types. (See Section A.18.)

that is defined for all

that is defined for all  and

and  .

What is meant by the integral of

.

What is meant by the integral of  along a given curve joining the points

along a given curve joining the points  and

and  in the

in the  -

- plane?

Well, we first draw out

plane?

Well, we first draw out  as a function of length

as a function of length  along the path. See Figure A.13. The integral is then simply given

by

along the path. See Figure A.13. The integral is then simply given

by

.

.

between

between  and

and  along the

two routes indicated in Figure A.14.

Along route 1 we have

along the

two routes indicated in Figure A.14.

Along route 1 we have  , so

, so

. Thus,

. Thus,

and

and  are evaluated

separately, rather that through the path length

are evaluated

separately, rather that through the path length  ; that is,

; that is,

![$\displaystyle \int_P^Q \left[ f(x,y)\,dx + g(x,y)\,dy\right].$](img4702.png)

![$\displaystyle \int_P^Q \left[ y\,dx + x^{\,3}\,dy\right]$](img4703.png)

and

and  , so

, so

![$\displaystyle \int_P^Q \left[ y\,dx + x^{\,3}\,dy\right]= \int_{0}^1\left[y\,dy + (y+1)^3\,dy\right] = \frac{17}{4}.$](img4706.png)

![$\displaystyle \int_P^Q \left[ y\,dx + x^{\,3}\,dy\right]= \left.\int_0^1 x^{\,3}\,dy\right\vert _{x=1} + \left.\int_1^2 y\,dx\right\vert _{y=1} = \frac{7}{4}.$](img4707.png)

. Given

. Given  for one point

for one point  in the

in the  -

- plane, then

plane, then

for all other points in the plane. We can then draw a contour map of

for all other points in the plane. We can then draw a contour map of  .

The line integral between points

.

The line integral between points  and

and  is simply the change in height in the contour

map between these two points:

is simply the change in height in the contour

map between these two points:

then

then

and

and

![$\displaystyle \int_P^Q \left(3\,x^{\,2}\,y\,dx + x^{\,3}\,dy\right) = \left[x^{\,3}\,y\right]_P^Q$](img4718.png)