Next: Cartesian Components of a

Up: Vector Algebra and Vector

Previous: Scalars and Vectors

Suppose that the displacements

and

and

represent the vectors

represent the vectors  and

and  , respectively--see Figure A.97. It can be seen that the result

of combining these two displacements is to give the net displacement

, respectively--see Figure A.97. It can be seen that the result

of combining these two displacements is to give the net displacement

. Hence,

if

. Hence,

if

represents the vector

represents the vector  then we can write

then we can write

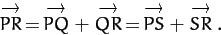

|

(1261) |

This defines vector addition.

By completing the parallelogram  , we can also see that

, we can also see that

|

(1262) |

However,

has the same length and direction as

has the same length and direction as

,

and, thus, represents the same vector,

,

and, thus, represents the same vector,  . Likewise,

. Likewise,

and

and

both represent the vector

both represent the vector  . Thus, the above equation is equivalent to

. Thus, the above equation is equivalent to

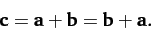

|

(1263) |

We conclude that the addition of vectors is commutative. It can also

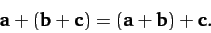

be shown that the associative law holds: i.e.,

|

(1264) |

The null vector,  , is represented by a displacement of zero length and arbitrary direction.

Since the result of combining such a displacement with a finite length displacement is the same

as the latter displacement by itself, it follows that

, is represented by a displacement of zero length and arbitrary direction.

Since the result of combining such a displacement with a finite length displacement is the same

as the latter displacement by itself, it follows that

|

(1265) |

where  is a general vector.

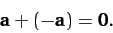

The negative of

is a general vector.

The negative of  is defined as that vector which has the same magnitude, but acts in the opposite direction, and is denoted

is defined as that vector which has the same magnitude, but acts in the opposite direction, and is denoted  .

The sum of

.

The sum of  and

and  is thus

the null vector: i.e.,

is thus

the null vector: i.e.,

|

(1266) |

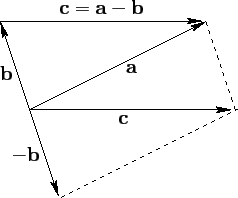

We can also define the difference of two vectors,  and

and  , as

, as

|

(1267) |

This definition of vector subtraction is illustrated in Figure A.98.

Figure A.98:

Vector subtraction.

|

If  is a scalar then the expression

is a scalar then the expression  denotes a vector whose direction is the same

as

denotes a vector whose direction is the same

as  , and whose magnitude

is

, and whose magnitude

is  times that of

times that of  . (This definition becomes obvious when

. (This definition becomes obvious when  is an integer.)

If

is an integer.)

If  is negative then, since

is negative then, since

, it follows

that

, it follows

that  is a vector whose magnitude is

is a vector whose magnitude is  times that of

times that of  , and whose

direction is opposite to

, and whose

direction is opposite to  . These definitions imply that if

. These definitions imply that if  and

and  are

two scalars then

are

two scalars then

Next: Cartesian Components of a

Up: Vector Algebra and Vector

Previous: Scalars and Vectors

Richard Fitzpatrick

2011-03-31

![]() , is represented by a displacement of zero length and arbitrary direction.

Since the result of combining such a displacement with a finite length displacement is the same

as the latter displacement by itself, it follows that

, is represented by a displacement of zero length and arbitrary direction.

Since the result of combining such a displacement with a finite length displacement is the same

as the latter displacement by itself, it follows that

![]() is a scalar then the expression

is a scalar then the expression ![]() denotes a vector whose direction is the same

as

denotes a vector whose direction is the same

as ![]() , and whose magnitude

is

, and whose magnitude

is ![]() times that of

times that of ![]() . (This definition becomes obvious when

. (This definition becomes obvious when ![]() is an integer.)

If

is an integer.)

If ![]() is negative then, since

is negative then, since

![]() , it follows

that

, it follows

that ![]() is a vector whose magnitude is

is a vector whose magnitude is ![]() times that of

times that of ![]() , and whose

direction is opposite to

, and whose

direction is opposite to ![]() . These definitions imply that if

. These definitions imply that if ![]() and

and ![]() are

two scalars then

are

two scalars then