Next: Energy of a Floating

Up: Hydrostatics

Previous: Angular Stability of Floating

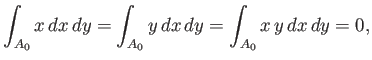

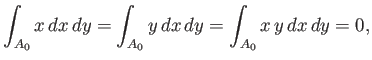

Suppose that the floating body considered in the previous section is in an equilibrium state.

Let  be the cross-sectional area at the waterline: that is, in the plane

be the cross-sectional area at the waterline: that is, in the plane  . Because the

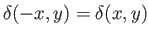

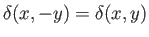

body is assumed to be symmetric with respect to

the

. Because the

body is assumed to be symmetric with respect to

the  and

and  planes, we have

planes, we have

|

(2.22) |

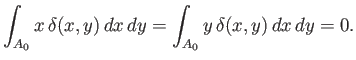

where the integrals are taken over the whole cross-section at  .

Let

.

Let

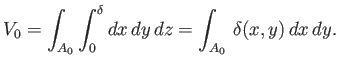

be the body's draft: that is, the vertical distance between the surface of the water and the body's lower boundary. It follows, from symmetry, that

be the body's draft: that is, the vertical distance between the surface of the water and the body's lower boundary. It follows, from symmetry, that

and

and

. Moreover, the submerged volume is

. Moreover, the submerged volume is

|

(2.23) |

It also follows from symmetry that

|

(2.24) |

The depth of the unperturbed center of buoyancy below the surface of the water is

|

(2.25) |

where

![$\displaystyle \delta_0 = \left[\frac{\int_{A_0}\delta^{\,2}(x,y)\,dx\,dy}{A_0}\right]^{1/2}.$](img634.png) |

(2.26) |

Finally, from symmetry, the unperturbed center of buoyancy lies at  .

.

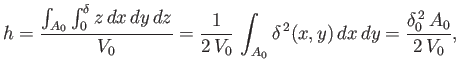

Suppose that the body now turns through a small angle  about the

about the  -axis.

As is easily demonstrated, the body's new draft becomes

-axis.

As is easily demonstrated, the body's new draft becomes

. Hence, the new submerged volume is

. Hence, the new submerged volume is

![$\displaystyle V_0'=\int_{A_0} [\delta(x,y) -\theta\,y]\,dx\,dy = V_0 + \theta\int_{A_0} y\,dx\,dy = V_0,$](img637.png) |

(2.27) |

where use has been made of Equations (2.22) and (2.23). Thus, the submerged volume is

unchanged, as should be the case for a purely angular displacement. The new depth of the center of buoyancy is

![$\displaystyle h' = \frac{\int_{A_0}\int_0^{\delta'} z\,dx\,dy\,dz}{V_0}=\frac{1...

...\,2}(x,y) -2\,\theta\,y\,\delta(x,y) + {\cal O}(\theta^{\,2})\right]dx\,dy = h,$](img638.png) |

(2.28) |

where use has been made of Equations (2.24) and (2.25). Thus, the depth of the center of buoyancy is also unchanged. Moreover, from symmetry, it

is clear that the center of buoyancy still lies at  . Finally, the new

. Finally, the new  -coordinate of

the center of buoyancy is

-coordinate of

the center of buoyancy is

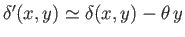

![$\displaystyle \frac{\int_{A_0}\int_0^{\delta'}y\,dx\,dy\,dz}{V_0}=\frac{\int_{A...

...[\delta(x,y)-\theta\,y]\,dx\,dy}{V_0}=-\theta\,\frac{\kappa_x^{\,2}\,A_0}{V_0},$](img639.png) |

(2.29) |

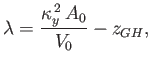

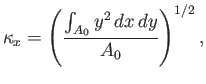

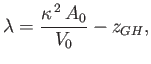

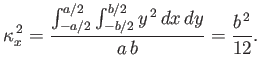

where use has been made of Equation (2.24). Here,

|

(2.30) |

is the radius of gyration of area  about the

about the  -axis.

-axis.

It follows, from the previous analysis, that if the floating body under consideration turns through a

small angle  about the

about the  -axis then its center of buoyancy shifts horizontally a distance

-axis then its center of buoyancy shifts horizontally a distance

in the plane perpendicular to the axis of rotation.

In other words, the distance

in the plane perpendicular to the axis of rotation.

In other words, the distance  in Figure 2.1 is

in Figure 2.1 is

. Simple trigonometry

reveals that

. Simple trigonometry

reveals that

(assuming that

(assuming that  is small). Hence,

is small). Hence,

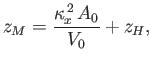

. Now,

. Now,  is the height of the metacenter

relative to the center of buoyancy. However, the center of buoyancy lies a depth

is the height of the metacenter

relative to the center of buoyancy. However, the center of buoyancy lies a depth  below the surface of the water (which corresponds to the plane

below the surface of the water (which corresponds to the plane  ).

Hence, the

).

Hence, the  -coordinate of the metacenter is

-coordinate of the metacenter is

. Finally, if

. Finally, if  and

and  are the

are the  -coordinates of the unperturbed

centers of gravity and buoyancy, respectively, then

-coordinates of the unperturbed

centers of gravity and buoyancy, respectively, then

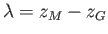

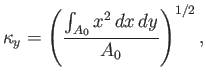

|

(2.31) |

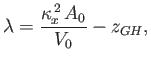

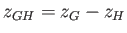

and

the metacentric height,

, becomes

, becomes

|

(2.32) |

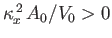

where

. Note that, because

. Note that, because

, the metacenter always lies above

the center of buoyancy.

, the metacenter always lies above

the center of buoyancy.

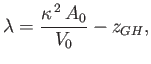

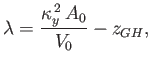

A simple extension of the previous argument reveals that if the body turns through

a small angle  about the

about the  -axis then the metacentric height is

-axis then the metacentric height is

|

(2.33) |

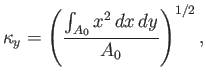

where

|

(2.34) |

is radius of gyration of area  about the

about the  -axis. Finally, as is easily demonstrated, if the body rotates about a

horizontal axis which subtends an angle

-axis. Finally, as is easily demonstrated, if the body rotates about a

horizontal axis which subtends an angle  with the

with the  -axis then

-axis then

|

(2.35) |

where

|

(2.36) |

Thus, the minimum value of

is the lesser of

is the lesser of

and

and

. It follows that

the equilibrium state in question is unconditionally stable provided it is stable to small

amplitude angular displacements about horizontal axes normal to its two vertical symmetry planes (i.e., the

. It follows that

the equilibrium state in question is unconditionally stable provided it is stable to small

amplitude angular displacements about horizontal axes normal to its two vertical symmetry planes (i.e., the  and

and

planes).

planes).

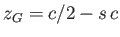

As an example, consider a uniform rectangular block of specific gravity  floating such that its sides

of length

floating such that its sides

of length  ,

,  , and

, and  are parallel to the

are parallel to the  -,

-,  -, and

-, and  -axes, respectively. Such a block can be

thought of as a very crude model of a ship.

The volume of the

block is

-axes, respectively. Such a block can be

thought of as a very crude model of a ship.

The volume of the

block is  . Hence, the submerged volume is

. Hence, the submerged volume is

. The cross-sectional

area of the block at the waterline (

. The cross-sectional

area of the block at the waterline ( ) is

) is  .

It is easily demonstrated that

.

It is easily demonstrated that

. Thus, the center of buoyancy lies a depth

. Thus, the center of buoyancy lies a depth

below

the surface of the water. [See Equation (2.25).] Moreover, by symmetry, the center of gravity is a height

below

the surface of the water. [See Equation (2.25).] Moreover, by symmetry, the center of gravity is a height  above the bottom surface of the block, which is located

a depth

above the bottom surface of the block, which is located

a depth  below the surface of the water. Hence,

below the surface of the water. Hence,

,

,

, and

, and

. Consider the

stability of the block to small amplitude angular displacements about the

. Consider the

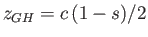

stability of the block to small amplitude angular displacements about the  -axis. We have

-axis. We have

|

(2.37) |

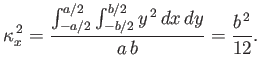

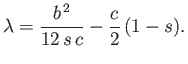

Hence, from Equation (2.32), the metacentric height is

|

(2.38) |

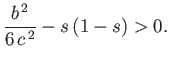

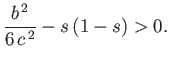

The stability criterion  yields

yields

|

(2.39) |

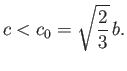

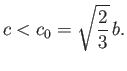

Because the maximum value that  can take is

can take is  , it follows that the block is stable for all

specific gravities when

, it follows that the block is stable for all

specific gravities when

|

(2.40) |

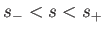

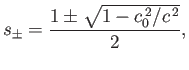

On the other hand, if  then the block is unstable for intermediate specific gravities such that

then the block is unstable for intermediate specific gravities such that

, where

, where

|

(2.41) |

and is stable otherwise.

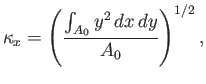

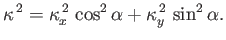

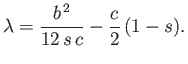

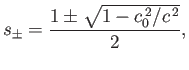

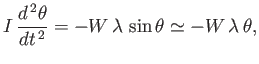

Assuming that the block is stable, its angular equation of motion is written

|

(2.42) |

where

![$\displaystyle I = \frac{W}{g\,V}\int_{-a/2}^{a/2}\int_{-b/2}^{b/2}\int_{-s\,c}^...

...,dx\,dy\,dz= \frac{W}{12\,g}\left(b^{\,2}+ 4\,[(1-s)^3+s^{\,3}]\,c^{\,2}\right)$](img684.png) |

(2.43) |

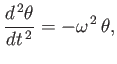

is the moment of inertia of the block about the  -axis. Thus, we obtain the the simple harmonic equation

-axis. Thus, we obtain the the simple harmonic equation

|

(2.44) |

where

![$\displaystyle \omega^{\,2} = \frac{W\,\lambda}{I}= \frac{g}{s\,c}\,\frac{c_0^{\,2}-4\,s\,(1-s)\,c^{\,2}}{c_0^{\,2}+(8/3)\,[(1-s)^3+s^{\,3}]\,c^{\,2}}.$](img686.png) |

(2.45) |

We conclude that the block executes small amplitude angular oscillations about the  -axis at the angular frequency

-axis at the angular frequency  . For the case of rotation about the

. For the case of rotation about the  -axis, the previous analysis

is unchanged except that

-axis, the previous analysis

is unchanged except that

. The previous analysis again neglects the phenomenon of added mass, and, therefore,

underestimates the effective inertia of the block. (See Sections 5.9 and 7.10.)

. The previous analysis again neglects the phenomenon of added mass, and, therefore,

underestimates the effective inertia of the block. (See Sections 5.9 and 7.10.)

The metacentric height of a conventional ship whose length greatly exceeds its width is typically

much less for rolling (i.e., rotation about a horizontal axis

running along the ship's length) than for pitching (i.e., rotation about a horizontal axis

perpendicular to the ship's length), because the radius of gyration for pitching greatly exceeds that for rolling.

As is clear

from Equation (2.45), a ship with a relatively small metacentric height (for rolling) has a relatively long roll period, and vice versa. An excessively low metacentric height increases the chances of a ship capsizing if the weather is rough, if its cargo/ballast shifts, or if the ship is

damaged and partially flooded. For this reason, maritime regulatory agencies, such as the International Maritime Organization, specify minimum metacentric heights for various different types of sea-going vessel. A relatively large metacentric height, on the other hand,

generally renders a ship uncomfortable for passengers and crew, because the ship executes short period rolls, resulting in large g-forces. Such forces also increase the risk that cargo may break loose or shift.

We saw earlier, in Section 2.4, that if a body of specific gravity  floats in vertical equilibrium in a certain position

then a body of the same shape, but of specific gravity

floats in vertical equilibrium in a certain position

then a body of the same shape, but of specific gravity  , can float in vertical equilibrium in the inverted position. We shall now

demonstrate that these positions are either both stable, or both unstable, provided the body is

of uniform density. Let

, can float in vertical equilibrium in the inverted position. We shall now

demonstrate that these positions are either both stable, or both unstable, provided the body is

of uniform density. Let  and

and  be

the volumes that are above and below the waterline, respectively, in the first position. Let

be

the volumes that are above and below the waterline, respectively, in the first position. Let  and

and

be the mean centers of these two volumes, and

be the mean centers of these two volumes, and  that of the whole volume. It follows that

that of the whole volume. It follows that

is the center of buoyancy in the first position,

is the center of buoyancy in the first position,  the center of buoyancy in the second (inverted) position, and

the center of buoyancy in the second (inverted) position, and

the center of gravity in both positions. Moreover,

the center of gravity in both positions. Moreover,

|

(2.46) |

where  is the distance between points

is the distance between points  and

and  , et cetera.

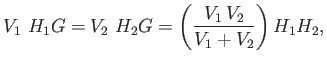

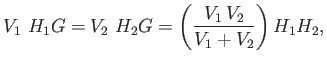

The metacentric heights in the first and second positions are

, et cetera.

The metacentric heights in the first and second positions are

respectively,

where  and

and  are the area and radius of gyration of the common waterline section, respectively.

Thus,

are the area and radius of gyration of the common waterline section, respectively.

Thus,

![$\displaystyle \lambda_1\,\lambda_2 = \frac{1}{V_1\,V_2}\left[A\,\kappa^{\,2}- \left(\frac{V_1\,V_2}{V_1+V_2}\right) H_1H_2\right]^{\,2}\geq 0,$](img698.png) |

(2.49) |

which implies that

as

as

, and vice versa. It follows that the first

and second positions are either both stable, both marginally stable, or both unstable.

, and vice versa. It follows that the first

and second positions are either both stable, both marginally stable, or both unstable.

Next: Energy of a Floating

Up: Hydrostatics

Previous: Angular Stability of Floating

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-03-31

![$\displaystyle \delta_0 = \left[\frac{\int_{A_0}\delta^{\,2}(x,y)\,dx\,dy}{A_0}\right]^{1/2}.$](img634.png)

![]() about the

about the ![]() -axis.

As is easily demonstrated, the body's new draft becomes

-axis.

As is easily demonstrated, the body's new draft becomes

![]() . Hence, the new submerged volume is

. Hence, the new submerged volume is

![$\displaystyle V_0'=\int_{A_0} [\delta(x,y) -\theta\,y]\,dx\,dy = V_0 + \theta\int_{A_0} y\,dx\,dy = V_0,$](img637.png)

![$\displaystyle h' = \frac{\int_{A_0}\int_0^{\delta'} z\,dx\,dy\,dz}{V_0}=\frac{1...

...\,2}(x,y) -2\,\theta\,y\,\delta(x,y) + {\cal O}(\theta^{\,2})\right]dx\,dy = h,$](img638.png)

![$\displaystyle \frac{\int_{A_0}\int_0^{\delta'}y\,dx\,dy\,dz}{V_0}=\frac{\int_{A...

...[\delta(x,y)-\theta\,y]\,dx\,dy}{V_0}=-\theta\,\frac{\kappa_x^{\,2}\,A_0}{V_0},$](img639.png)

![]() about the

about the ![]() -axis then its center of buoyancy shifts horizontally a distance

-axis then its center of buoyancy shifts horizontally a distance

![]() in the plane perpendicular to the axis of rotation.

In other words, the distance

in the plane perpendicular to the axis of rotation.

In other words, the distance ![]() in Figure 2.1 is

in Figure 2.1 is

![]() . Simple trigonometry

reveals that

. Simple trigonometry

reveals that

![]() (assuming that

(assuming that ![]() is small). Hence,

is small). Hence,

![]() . Now,

. Now, ![]() is the height of the metacenter

relative to the center of buoyancy. However, the center of buoyancy lies a depth

is the height of the metacenter

relative to the center of buoyancy. However, the center of buoyancy lies a depth ![]() below the surface of the water (which corresponds to the plane

below the surface of the water (which corresponds to the plane ![]() ).

Hence, the

).

Hence, the ![]() -coordinate of the metacenter is

-coordinate of the metacenter is

![]() . Finally, if

. Finally, if ![]() and

and ![]() are the

are the ![]() -coordinates of the unperturbed

centers of gravity and buoyancy, respectively, then

-coordinates of the unperturbed

centers of gravity and buoyancy, respectively, then

![]() about the

about the ![]() -axis then the metacentric height is

-axis then the metacentric height is

![]() floating such that its sides

of length

floating such that its sides

of length ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are parallel to the

are parallel to the ![]() -,

-, ![]() -, and

-, and ![]() -axes, respectively. Such a block can be

thought of as a very crude model of a ship.

The volume of the

block is

-axes, respectively. Such a block can be

thought of as a very crude model of a ship.

The volume of the

block is ![]() . Hence, the submerged volume is

. Hence, the submerged volume is

![]() . The cross-sectional

area of the block at the waterline (

. The cross-sectional

area of the block at the waterline (![]() ) is

) is ![]() .

It is easily demonstrated that

.

It is easily demonstrated that

![]() . Thus, the center of buoyancy lies a depth

. Thus, the center of buoyancy lies a depth

![]() below

the surface of the water. [See Equation (2.25).] Moreover, by symmetry, the center of gravity is a height

below

the surface of the water. [See Equation (2.25).] Moreover, by symmetry, the center of gravity is a height ![]() above the bottom surface of the block, which is located

a depth

above the bottom surface of the block, which is located

a depth ![]() below the surface of the water. Hence,

below the surface of the water. Hence,

![]() ,

,

![]() , and

, and

![]() . Consider the

stability of the block to small amplitude angular displacements about the

. Consider the

stability of the block to small amplitude angular displacements about the ![]() -axis. We have

-axis. We have

![$\displaystyle I = \frac{W}{g\,V}\int_{-a/2}^{a/2}\int_{-b/2}^{b/2}\int_{-s\,c}^...

...,dx\,dy\,dz= \frac{W}{12\,g}\left(b^{\,2}+ 4\,[(1-s)^3+s^{\,3}]\,c^{\,2}\right)$](img684.png)

![]() floats in vertical equilibrium in a certain position

then a body of the same shape, but of specific gravity

floats in vertical equilibrium in a certain position

then a body of the same shape, but of specific gravity ![]() , can float in vertical equilibrium in the inverted position. We shall now

demonstrate that these positions are either both stable, or both unstable, provided the body is

of uniform density. Let

, can float in vertical equilibrium in the inverted position. We shall now

demonstrate that these positions are either both stable, or both unstable, provided the body is

of uniform density. Let ![]() and

and ![]() be

the volumes that are above and below the waterline, respectively, in the first position. Let

be

the volumes that are above and below the waterline, respectively, in the first position. Let ![]() and

and

![]() be the mean centers of these two volumes, and

be the mean centers of these two volumes, and ![]() that of the whole volume. It follows that

that of the whole volume. It follows that

![]() is the center of buoyancy in the first position,

is the center of buoyancy in the first position, ![]() the center of buoyancy in the second (inverted) position, and

the center of buoyancy in the second (inverted) position, and

![]() the center of gravity in both positions. Moreover,

the center of gravity in both positions. Moreover,

![$\displaystyle = \frac{\kappa^{\,2}\,A}{V_1} - H_1G =\frac{1}{V_1}\left[A\,\kappa^{\,2}- \left(\frac{V_1\,V_2}{V_1+V_2}\right) H_1H_2\right],$](img695.png)

![$\displaystyle = \frac{\kappa^{\,2}\,A}{V_2} - H_2G =\frac{1}{V_2}\left[A\,\kappa^{\,2}- \left(\frac{V_1\,V_2}{V_1+V_2}\right)H_1H_2\right],$](img697.png)

![$\displaystyle \lambda_1\,\lambda_2 = \frac{1}{V_1\,V_2}\left[A\,\kappa^{\,2}- \left(\frac{V_1\,V_2}{V_1+V_2}\right) H_1H_2\right]^{\,2}\geq 0,$](img698.png)