Next: Exercises

Up: Equilibrium of Compressible Fluids

Previous: Atmospheric Stability

Eddington Solar Model

Let us

investigate the internal structure of the Sun, which is basically a self-gravitating sphere of incandescent ionized gas (consisting mostly of hydrogen). Adopting a spherical coordinate system (see Section C.4),  ,

,  ,

,  ,

whose origin coincides with the Sun's geometric center, and making the simplifying (and highly accurate) assumption that the mass

distribution within the Sun is spherically symmetric, we find that

,

whose origin coincides with the Sun's geometric center, and making the simplifying (and highly accurate) assumption that the mass

distribution within the Sun is spherically symmetric, we find that

|

(13.21) |

where  is the total mass contained within a sphere of radius

is the total mass contained within a sphere of radius  , centered on the origin, and

, centered on the origin, and  the mass density at radius

the mass density at radius  . Now, as is well known, the gravitational

acceleration at some radius

. Now, as is well known, the gravitational

acceleration at some radius  in a spherically symmetric mass distribution is the same as would be obtained were all the mass located within this radius concentrated at the center, and

the remainder of the mass neglected (Fitzpatrick 2012). In other words,

in a spherically symmetric mass distribution is the same as would be obtained were all the mass located within this radius concentrated at the center, and

the remainder of the mass neglected (Fitzpatrick 2012). In other words,

|

(13.22) |

where

is the gravitational potential energy per unit mass, and

is the gravitational potential energy per unit mass, and

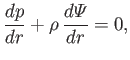

the radial gravitational acceleration. The force balance criterion (13.1)

yields

the radial gravitational acceleration. The force balance criterion (13.1)

yields

|

(13.23) |

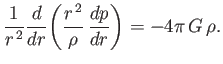

where  is the pressure. The previous three equations can be combined to give

is the pressure. The previous three equations can be combined to give

|

(13.24) |

In order to make any further progress, we need to determine the relationship between the Sun's internal pressure and

density. Unfortunately, this relationship is ultimately controlled by energy transport, which is

a very complicated process in a star. In fact, a star's energy is ultimately derived from nuclear reactions

occurring deep within its core, the details of which are extremely complicated. This energy is then transported from the core to the outer boundary

via a combination of convection and radiation. (Conduction plays a much less important role in this process.) Unfortunately, an exact calculation of radiative transport requires an understanding of the opacity of stellar material, which is an exceptionally

difficult subject.

Finally, once the energy reaches the boundary of the star, it

is radiated away. The following ingenious model, due to Eddington (Eddington 1926), is appropriate to a star whose internal

energy transport is dominated by radiation. This turns out to be a fairly good approximation for the Sun.

The main advantage of Eddington's model is that it does not require us to know anything about stellar nuclear reactions or opacity.

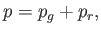

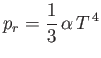

Now, the temperature inside the Sun is sufficiently high that radiation pressure cannot be completely neglected with respect to conventional gas pressure.

In other words, we must write the solar equation of state in the form

|

(13.25) |

where

|

(13.26) |

is the gas pressure (modeling the plasma within the Sun as an ideal gas of free electrons and

ions), and (Chandrasekhar 1967)

|

(13.27) |

the radiation pressure (assuming that the radiation within the Sun is everywhere in local thermodynamic equilibrium with the plasma). Here,  is the Sun's internal temperature,

is the Sun's internal temperature,  the Boltzmann constant,

the Boltzmann constant,  the mass

of a proton, and

the mass

of a proton, and  the relative molecular mass (i.e., the ratio of the mean

mass of the free particles making up the solar plasma to that of a proton). Note that the electron mass

has been neglected with respect to that of a proton.

Furthermore,

the relative molecular mass (i.e., the ratio of the mean

mass of the free particles making up the solar plasma to that of a proton). Note that the electron mass

has been neglected with respect to that of a proton.

Furthermore,

,

where

,

where  is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, and

is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, and  the velocity of light in a vacuum. Incidentally, in

writing Equation (13.26), we have expressed

the velocity of light in a vacuum. Incidentally, in

writing Equation (13.26), we have expressed  in the equivalent form

in the equivalent form

.

.

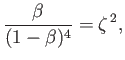

Let

where the parameter  is assumed to be uniform. In other words, the

ratio of the radiation pressure to the gas pressure is assumed to be the same everywhere inside the Sun.

This fairly drastic

assumption turns out--perhaps, somewhat fortuitously (Mestel 1999)--to lead to approximately the correct

internal pressure-density relation for the Sun. In fact, Equations (13.26)-(13.29)

can be combined to give

is assumed to be uniform. In other words, the

ratio of the radiation pressure to the gas pressure is assumed to be the same everywhere inside the Sun.

This fairly drastic

assumption turns out--perhaps, somewhat fortuitously (Mestel 1999)--to lead to approximately the correct

internal pressure-density relation for the Sun. In fact, Equations (13.26)-(13.29)

can be combined to give

|

(13.30) |

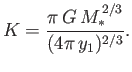

where

![$\displaystyle K = \left[\left(\frac{k}{m_p}\right)^4\,\frac{3}{\alpha}\,\frac{\beta}{\mu^{\,4}\,(1-\beta)^4}\right]^{1/3}.$](img5193.png) |

(13.31) |

It can be seen, by comparison with Equation (13.4), that the previous pressure-density relation takes the form of an adiabatic gas law with an effective ratio of specific heats

. Note, however, that the actual ratio of specific heats for a fully ionized hydrogen plasma, in the

absence of radiation,

is

. Note, however, that the actual ratio of specific heats for a fully ionized hydrogen plasma, in the

absence of radiation,

is

. Hence, the

. Hence, the  exponent, appearing in Equation (13.30), is entirely due to the non-negligible radiation pressure

within the Sun.

exponent, appearing in Equation (13.30), is entirely due to the non-negligible radiation pressure

within the Sun.

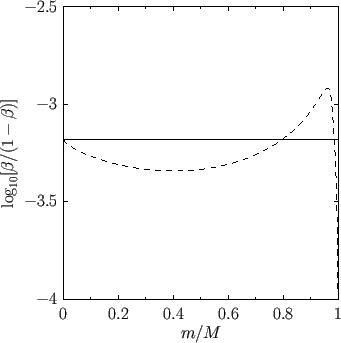

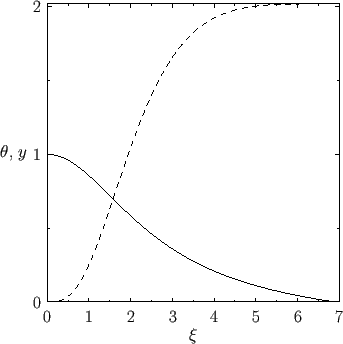

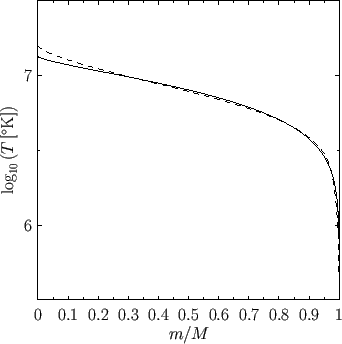

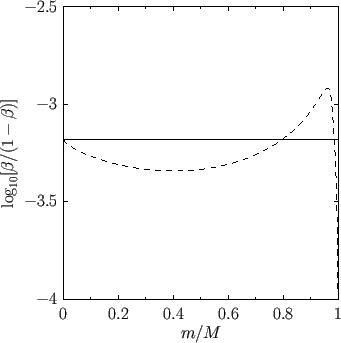

Figure:

The functions

(solid) and

(solid) and  (dashed).

(dashed).

|

Let

,

,

, and

, and

, be the Sun's central temperature, density, and

pressure, respectively. It follows from Equation (13.30) that

, be the Sun's central temperature, density, and

pressure, respectively. It follows from Equation (13.30) that

|

(13.32) |

and from Equations (13.26) and (13.28) that

|

(13.33) |

Suppose that

|

(13.34) |

where  is a dimensionless function.

According to Equations (13.26), (13.28), and (13.30),

is a dimensionless function.

According to Equations (13.26), (13.28), and (13.30),

Moreover, it is clear, from the previous expressions, that  at the center of the Sun,

at the center of the Sun,  , and

, and

at the edge,

at the edge,  (say), where the temperature, density, and pressure are all

assumed to fall to zero.

Suppose, finally, that

(say), where the temperature, density, and pressure are all

assumed to fall to zero.

Suppose, finally, that

|

(13.37) |

where  is a dimensionless radial coordinate, and

is a dimensionless radial coordinate, and

|

(13.38) |

Thus, the center of the Sun corresponds to  , and the edge to

, and the edge to  (say), where

(say), where

, and

, and

|

(13.39) |

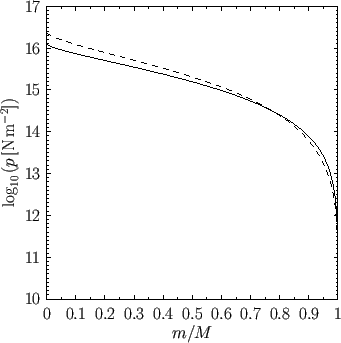

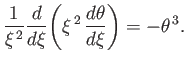

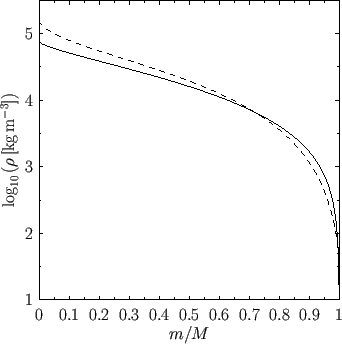

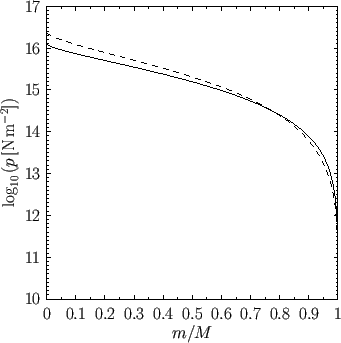

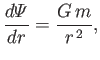

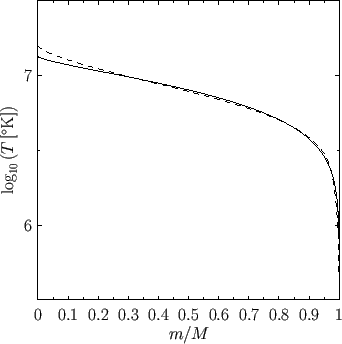

Figure 13.2:

Solar temperature versus mass fraction obtained from the Eddington Solar Model (solid) and

the Standard Solar Model (dashed).

|

Equations (13.35)-(13.38) can be used to transform the equilibrium relation (13.24) into

the non-dimensional form

|

(13.40) |

Moreover, Equation (13.21) can be integrated, with the aid of Equations (13.35), (13.37), and (13.40),

and the physical boundary condition  , to give

, to give

|

(13.41) |

where

|

(13.42) |

Equation (13.40) is known as the Lane-Emden equation (of degree  ), and can, unfortunately, only be

solved numerically (Chandrasekhar 1967). The appropriate solution takes the form

), and can, unfortunately, only be

solved numerically (Chandrasekhar 1967). The appropriate solution takes the form

when

when  ,

and must be

integrated to

,

and must be

integrated to  , where

, where

. Figure 13.1 shows

. Figure 13.1 shows

, and the

related function

, and the

related function  , obtained via numerical methods. Note that

, obtained via numerical methods. Note that

, and

, and

.

.

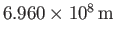

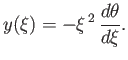

Figure 13.3:

Solar mass density versus mass fraction obtained from the Eddington Solar Model (solid) and

the Standard Solar Model (dashed).

|

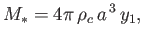

According to Equation (13.41), the solar mass,

,

can be written

,

can be written

|

(13.43) |

which reduces, with the aid of Equations (13.31) and (13.38), to

|

(13.44) |

where

|

(13.45) |

and

![$\displaystyle M_0 = \left[\frac{1}{(\pi\,G)^3}\left(\frac{k}{m_p}\right)^4\,\frac{3}{\alpha}\right]^{1/2}4\pi\,y_1 = 3.586\times 10^{31}\,{\rm kg}.$](img5229.png) |

(13.46) |

Moreover, it is easily demonstrated that

|

(13.47) |

According to Equations (13.44) and (13.45), the ratio,

, of the radiation

pressure to the gas pressure in a radiative star is a strongly increasing function of the stellar mass,

, of the radiation

pressure to the gas pressure in a radiative star is a strongly increasing function of the stellar mass,  , and mean molecular weight,

, and mean molecular weight,  .

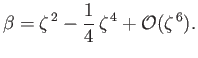

In the case of the Sun, for which

.

In the case of the Sun, for which

, Equation (13.44) can be inverted to give the approximate

solution

, Equation (13.44) can be inverted to give the approximate

solution

|

(13.48) |

Using the observed solar mass

, and the value

, and the value  (which represents the best fit to the Standard Solar Model

mentioned in the following), we find that

(which represents the best fit to the Standard Solar Model

mentioned in the following), we find that

. In other words, the radiation pressure

inside the Sun is only a very small fraction of the gas pressure. This immediately implies that radiative energy transport is

much less efficient than convective energy transport. Indeed, in regions of the Sun in which convection occurs, we would

expect the convective transport to overwhelm the radiative transport, and so to drive the local pressure-density

relation toward an adiabatic law with an exponent

. In other words, the radiation pressure

inside the Sun is only a very small fraction of the gas pressure. This immediately implies that radiative energy transport is

much less efficient than convective energy transport. Indeed, in regions of the Sun in which convection occurs, we would

expect the convective transport to overwhelm the radiative transport, and so to drive the local pressure-density

relation toward an adiabatic law with an exponent  . Fortunately, convection only takes place in the Sun's

outer regions, which contain a minuscule fraction of its mass.

. Fortunately, convection only takes place in the Sun's

outer regions, which contain a minuscule fraction of its mass.

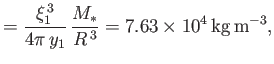

Figure 13.4:

Solar pressure versus mass fraction obtained from the Eddington Solar Model (solid) and

the Standard Solar Model (dashed).

|

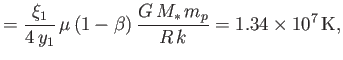

Equations (13.32), (13.33), (13.39), (13.43), and (13.47) yield

where the solar radius  has been given the observed value

has been given the observed value

.

The actual values of the Sun's central temperature, density, and pressure, as determined by the

so-called Standard Solar Model (SSM),13.1which incorporates detailed treatments of nuclear reactions and opacity,

are

.

The actual values of the Sun's central temperature, density, and pressure, as determined by the

so-called Standard Solar Model (SSM),13.1which incorporates detailed treatments of nuclear reactions and opacity,

are

,

,

, and

, and

, respectively. It can be seen that the values of

, respectively. It can be seen that the values of  ,

,  , and

, and  obtained from the Eddington model

lie within a factor of two of those obtained from the much more accurate SSM.

Figures 13.2, 13.3, and 13.4 show the temperature, density, and pressure

profiles, respectively, obtained from the SSM13.2 and the Eddington model. The profiles are plotted as functions of the mass

fraction,

obtained from the Eddington model

lie within a factor of two of those obtained from the much more accurate SSM.

Figures 13.2, 13.3, and 13.4 show the temperature, density, and pressure

profiles, respectively, obtained from the SSM13.2 and the Eddington model. The profiles are plotted as functions of the mass

fraction,

, where

, where  . It can be seen that there is fairly good agreement between the profiles

calculated by the two

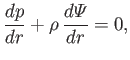

models. Finally, Figure 13.5 compares the ratio,

. It can be seen that there is fairly good agreement between the profiles

calculated by the two

models. Finally, Figure 13.5 compares the ratio,

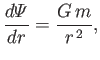

, of the radiation pressure to the

gas pressure obtained from the SSM and the Eddington model. Recall, that it is a fundamental assumption of the

Eddington model that this pressure ratio is uniform throughout the Sun. In fact, it can be seen that the pressure ratio

calculated by the

SSM is not spatially uniform. On the other hand, the spatial variation of the ratio is fairly weak, except close

to the edge of the Sun, where convection sets in, and the Eddington model, thus, becomes invalid. We conclude that, despite its

simplicity, the Eddington solar model

does a remarkably good job of accounting for the Sun's internal structure.

, of the radiation pressure to the

gas pressure obtained from the SSM and the Eddington model. Recall, that it is a fundamental assumption of the

Eddington model that this pressure ratio is uniform throughout the Sun. In fact, it can be seen that the pressure ratio

calculated by the

SSM is not spatially uniform. On the other hand, the spatial variation of the ratio is fairly weak, except close

to the edge of the Sun, where convection sets in, and the Eddington model, thus, becomes invalid. We conclude that, despite its

simplicity, the Eddington solar model

does a remarkably good job of accounting for the Sun's internal structure.

Figure 13.5:

Ratio of radiation pressure to gas pressure calculated from the Eddington Solar Model (solid) and

the Standard Solar Model (dashed).

|

Next: Exercises

Up: Equilibrium of Compressible Fluids

Previous: Atmospheric Stability

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-03-31

![]() ,

,

![]() , and

, and

![]() , be the Sun's central temperature, density, and

pressure, respectively. It follows from Equation (13.30) that

, be the Sun's central temperature, density, and

pressure, respectively. It follows from Equation (13.30) that

![]() ,

can be written

,

can be written

![$\displaystyle M_0 = \left[\frac{1}{(\pi\,G)^3}\left(\frac{k}{m_p}\right)^4\,\frac{3}{\alpha}\right]^{1/2}4\pi\,y_1 = 3.586\times 10^{31}\,{\rm kg}.$](img5229.png)