Next: Non-Global Ocean Tides

Up: Terrestrial Ocean Tides

Previous: Response to Equilibrium Harmonic

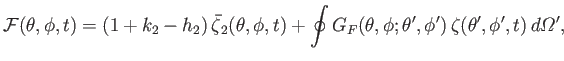

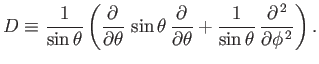

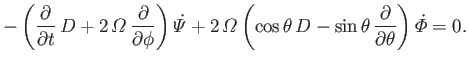

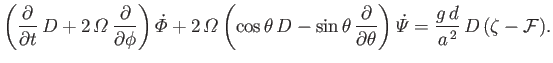

Suppose that the surface of the Earth is completely covered by an ocean of uniform mean depth  .

The motion of this ocean under the action of the tide generating potential is governed by

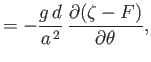

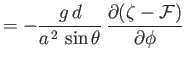

the Laplace tidal equations, (12.139)-(12.141), which can be written

.

The motion of this ocean under the action of the tide generating potential is governed by

the Laplace tidal equations, (12.139)-(12.141), which can be written

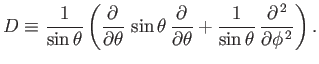

where

|

(12.152) |

and

Here,

.

.

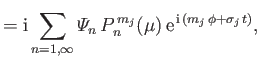

It is convenient to write (Love 1913)

It follows from Equation (12.153) that

|

(12.157) |

where

|

(12.158) |

Forming

![% latex2html id marker 87763

$ (\sin\theta)^{-1}\,\partial(\ref{e129c})/\partial\phi-(\sin\theta)^{-1}\,\partial[\sin\theta(\ref{e130c})/\partial\theta]$](img4668.png) , we

obtain

, we

obtain

|

(12.159) |

Similarly, forming

![% latex2html id marker 87767

$ -(\sin\theta)^{-1}\,(\partial/\partial\theta)\,[\sin\theta\,(\ref{e129c})]

-(\sin\theta)^{-1}\,\partial(\ref{e130c})/\partial\phi$](img4670.png) , we get

, we get

|

(12.160) |

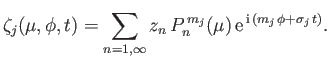

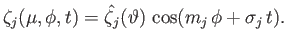

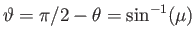

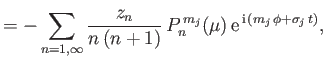

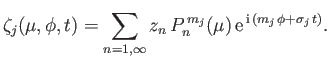

Let

. Consider the response,

. Consider the response,

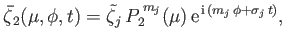

, of the ocean to a particular harmonic of the forcing term that takes the form [see Equation (12.143)]

, of the ocean to a particular harmonic of the forcing term that takes the form [see Equation (12.143)]

|

(12.161) |

where

is a constant. We can write

is a constant. We can write

where the

are associated Legendre functions, and the

are associated Legendre functions, and the  and

and

are constants.

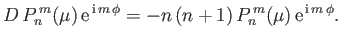

Now, by definition (Abramowitz and Stegun 1965),

are constants.

Now, by definition (Abramowitz and Stegun 1965),

|

(12.164) |

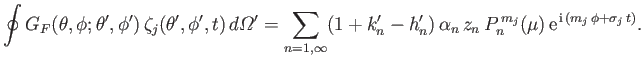

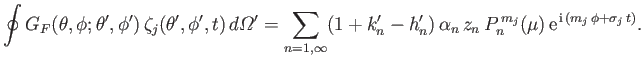

Hence, Equations (12.161) and (12.166) give

|

(12.165) |

Equations (12.136) and (12.138) imply that

|

(12.166) |

It follows from Equations (12.163) and (12.164) that

![$\displaystyle \sum_{n=1,\infty}\left\{{\mit\Psi}_n\left[-f_j\,n\,(n+1)+m_j\righ...

...ac{(1-\mu^{\,2})}{n\,(n+1)}\,\frac{d}{d\mu}\right]P_n^{\,m_j}(\mu)\right\} = 0,$](img4684.png) |

(12.167) |

and

where (Lamb 1993)

However, as is well known (Abramowitz and Stegun 1965),

Equations (12.171), (12.172), (12.175), and (12.176) can be combined to give

![$\displaystyle \left[m_j-n\,(n+1)\,f_j\right]{\mit\Psi}_n + \left(\frac{n+1}{n}\...

...n-1}\right)z_{n-1}+\left(\frac{n}{n+1}\,\frac{n+m_j+1}{2\,n+3}\right)z_{n+1}=0,$](img4693.png) |

(12.172) |

and

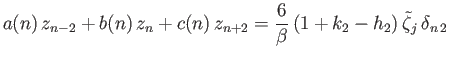

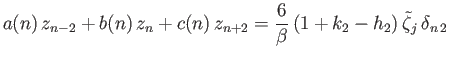

Finally, Equations (12.177) and (12.178) yield the tridiagonal matrix equation (Love 1913)

|

(12.174) |

for  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , where

, where

|

![$\displaystyle = - \frac{f_j\,n\,(n+1)\,(n-m_j-1)\,(n-m_j)}{(2\,n-3)\,(2\,n-1)\,[m_j-n\,(n-1)\,f_j]},$](img4701.png) |

(12.175) |

|

![$\displaystyle = \frac{n\,(n+1)}{\beta}\left(1-[1+k_n'-h_n']\,\alpha_n\right) + \frac{m_j\,f_j}{n\,(n+1)}-f_j^{\,2}$](img4703.png) |

|

| |

![$\displaystyle \phantom{=}- \frac{f_j\,(n-1)^2\,(n+1)\,(n-m_j)\,(n+m_j)}{n\,(2\,n-1)\,(2\,n+1)\,[m_j-n\,(n-1)\,f_j]}$](img4704.png) |

|

| |

![$\displaystyle \phantom{=}-\frac{f_j\,(n+2)^2\,n\,(n-m_j+1)\,(n+m_j+1)}{(n+1)\,(2\,n+1)\,(2\,n+3)\,[m_j-(n+1)\,(n+2)\,f_j]},$](img4705.png) |

(12.176) |

|

![$\displaystyle =-\frac{f_j\,n\,(n+1)\,(n+m_j+1)\,(n+m_j+2)}{(2\,n+3)\,(2\,n+5)\,[m_j-(n+1)\,(n+2)\,f_j]}.$](img4707.png) |

(12.177) |

Note that  .

The solution of a tridiagonal matrix equation is, of course, a relatively trivial numerical exercise (Press, et al. 2007).

.

The solution of a tridiagonal matrix equation is, of course, a relatively trivial numerical exercise (Press, et al. 2007).

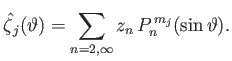

We can most conveniently characterize the  th tidal harmonic in terms of the function

th tidal harmonic in terms of the function

,

which is defined such that

,

which is defined such that

|

(12.178) |

Here,

represents planetary latitude.

It follows that

represents planetary latitude.

It follows that

|

(12.179) |

The

,

,  , and

, and  values for the various harmonics of the forcing term in the Laplace tidal equations for the Earth are specified in Table 12.3.

Note that, on the longitudinal meridian

values for the various harmonics of the forcing term in the Laplace tidal equations for the Earth are specified in Table 12.3.

Note that, on the longitudinal meridian  , the Moon and Sun culminate simultaneously at

, the Moon and Sun culminate simultaneously at  . Moreover, at this time, the Sun and Moon are both passing though the summer solstice, and the Moon is passing though its perigee.

The mean density of the Earth is such that

. Moreover, at this time, the Sun and Moon are both passing though the summer solstice, and the Moon is passing though its perigee.

The mean density of the Earth is such that

(Yoder 1995).

Moreover, the mean depth of the Earth's oceans is

(Yoder 1995).

Moreover, the mean depth of the Earth's oceans is

(Yoder 1995), which implies that

(Yoder 1995), which implies that

.

Finally, the Earth responds

elastically to the relatively low-amplitude lunar and solar tidal gravitational fields in such a manner that

.

Finally, the Earth responds

elastically to the relatively low-amplitude lunar and solar tidal gravitational fields in such a manner that

(Fitzpatrick 2012).

(Fitzpatrick 2012).

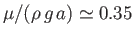

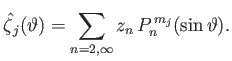

Figure:

Long-period solutions to the Laplace tidal equations (left panel) together with the corresponding equilibrium tides (right panel). The solid, dashed, and dash-dotted lines correspond to  ,

,  , and

, and  , respectively. Here,

, respectively. Here,

is measured in meters.

is measured in meters.

|

Figures 12.1, 12.2, and 12.3 show the long-period, diurnal, and semi-diurnal solutions of the Laplace tidal

equations together with the corresponding equilibrium tides (i.e., the tides calculated in the absence of

ocean inertia),

![$\displaystyle \skew{5}\hat{\zeta}_j(\vartheta)= \left[\frac{1+k_2-h_2}{1-(1+k_2'-h_2')\,\alpha_2}\right]\skew{5}\tilde{\zeta}_j\,P_2^{\,m_j}(\sin\vartheta).$](img4719.png) |

(12.180) |

It can be seen from Figure 12.1 that the long-period solutions are direct (i.e., they have the same signs as the corresponding equilibrium tides).

However, the amplitudes of these solutions are about  times lower than those of the equilibrium tides. The

times lower than those of the equilibrium tides. The  (

( ) and

) and

(

( ) solutions cause a slight increase in the equatorial bulge of the Earth's oceans when the Sun and Moon, respectively, pass through the equinoxes,

and a slight reduction when they pass through the solstices. The

) solutions cause a slight increase in the equatorial bulge of the Earth's oceans when the Sun and Moon, respectively, pass through the equinoxes,

and a slight reduction when they pass through the solstices. The  (

( ) solution causes a slight increase in the equatorial bulge of the Earth's oceans when the Moon

passes through its perigee, and a slight reduction when it passes through its apogee.

) solution causes a slight increase in the equatorial bulge of the Earth's oceans when the Moon

passes through its perigee, and a slight reduction when it passes through its apogee.

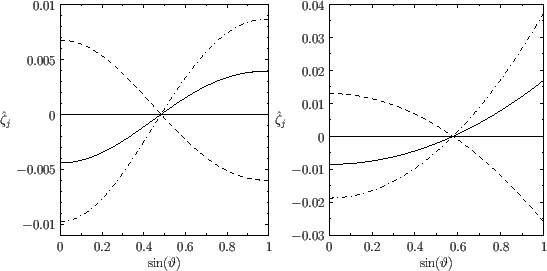

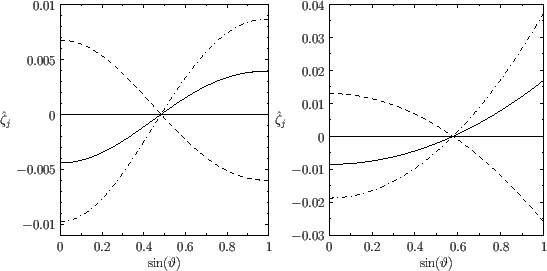

Figure:

Diurnal solutions to the Laplace tidal equations (left panel) together with the corresponding equilibrium tides (right panel). The solid, dashed, and dash-dotted lines correspond to  ,

,  , and

, and  , respectively. Here,

, respectively. Here,

is measured in meters.

is measured in meters.

|

It can be seen from Figure 12.2 that the diurnal solutions are inverted (i.e., they have the opposite signs to the corresponding equilibrium tides).

The amplitude of

the  solution is about

solution is about  times lower than that of the

times lower than that of the  equilibrium tide. The amplitudes of the

equilibrium tide. The amplitudes of the  and

and  solutions are negligibly small. (In fact,

the amplitude of the

solutions are negligibly small. (In fact,

the amplitude of the  solution is identically zero.) The

solution is identically zero.) The  (

( ) solution causes the Earth's oceans to displace slightly toward the Moon when it passes

through the equinoxes, and away from the Moon when it passes through the solstices.

) solution causes the Earth's oceans to displace slightly toward the Moon when it passes

through the equinoxes, and away from the Moon when it passes through the solstices.

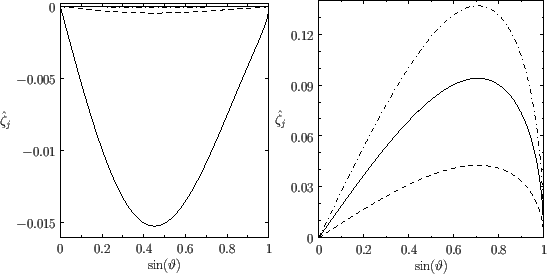

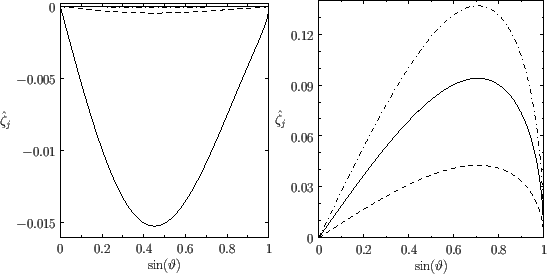

Figure:

Semi-diurnal solutions to the Laplace tidal equations (left panel) together with the corresponding equilibrium tides (right panel). The solid, dashed, and dash-dotted lines correspond to  ,

,  , and

, and  , respectively. Here,

, respectively. Here,

is measured in meters.

is measured in meters.

|

Finally, it can be seen from Figure 12.3 that the semi-diurnal solutions are inverted in equatorial regions, and direct in polar regions. Moreover,

the amplitudes of these solutions are similar to those of the corresponding equilibrium tides. The dominant  (

( ) solution generates a high tide

at a particular point on the Earth's surface every

) solution generates a high tide

at a particular point on the Earth's surface every  hours. The

hours. The  (

( ) solution causes an enhancement of the high tide--a so-called spring tide--at the new and

full moons (i.e., every half a synodic month, or

) solution causes an enhancement of the high tide--a so-called spring tide--at the new and

full moons (i.e., every half a synodic month, or  days). Finally, the

days). Finally, the  (

( ) solution causes an enhancement of the spring tide--a so-called perigean spring tide--whenever the new or full moon coincides with the passage of the moon through its perigee.

) solution causes an enhancement of the spring tide--a so-called perigean spring tide--whenever the new or full moon coincides with the passage of the moon through its perigee.

The previously described global solutions to the Laplace tidal equations were first obtained (in simplified form) by Laplace (Lamb 1993). Let us consider how these solutions

compare with the observed terrestrial tides. One obvious prediction of the global solutions is that the time variation in ocean

depth at a given point on the Earth's surface should be expressible as a superposition of terms that oscillate at constant amplitude (but not

necessarily in phase with one another) with the periods specified in Table 12.3. This is indeed found to be the case (Cartwright 1999).

Another prediction is that the amplitudes of the long-period solutions should be small compared to the amplitudes

of the semi-diurnal solutions. This is also found to be the case. Yet another prediction is that amplitudes of the diurnal solutions should be small compared to the amplitudes

of the semi-diurnal solutions. This turns out not to be the case (Cartwright 1999). In fact, this predication is an artifact of the fact that we are assuming that

the ocean covering the Earth's surface is of constant mean depth. If we relax this assumption, and allow the ocean depth to vary in a realistic manner, then the amplitudes of the

semi-diurnal solutions become comparable to those of the diurnal solutions (Lamb 1993). The final prediction

is that a given solution is such that the tide at a given point on the Earth either oscillates in phase or in anti-phase with the corresponding

equilibrium solution (i.e., the tide is either direct or inverted). In particular, for the dominant  tide, this

implies that, at a given point on the Earth's surface, there should be either a tidal maximum or a tidal minimum whenever the Moon culminates.

It turns out that this is not the case (Cartwright 1999). Indeed, the observed phase difference between the

tide, this

implies that, at a given point on the Earth's surface, there should be either a tidal maximum or a tidal minimum whenever the Moon culminates.

It turns out that this is not the case (Cartwright 1999). Indeed, the observed phase difference between the  tide and the corresponding

equilibrium tide varies from place to place on the Earth's surface, and can take any value. In other words, high tide at a given point on the Earth can

occur three hours before the Moon culminates, or two hours after, et cetera, and the time lag between high tide and the culmination of the Moon

varies from place to place.

We conjecture that this effect is caused by the

continents impeding the flow of tidal waves around the Earth. Hence, we now need to consider tides in oceans that do not

cover the whole surface of the Earth.

tide and the corresponding

equilibrium tide varies from place to place on the Earth's surface, and can take any value. In other words, high tide at a given point on the Earth can

occur three hours before the Moon culminates, or two hours after, et cetera, and the time lag between high tide and the culmination of the Moon

varies from place to place.

We conjecture that this effect is caused by the

continents impeding the flow of tidal waves around the Earth. Hence, we now need to consider tides in oceans that do not

cover the whole surface of the Earth.

Next: Non-Global Ocean Tides

Up: Terrestrial Ocean Tides

Previous: Response to Equilibrium Harmonic

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-03-31

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{\sin\theta}\left[\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta}\,(\sin\theta\,\xi)+ \frac{\partial\eta}{\partial\phi}\right] + \zeta$](img4654.png)

![]() . Consider the response,

. Consider the response,

![]() , of the ocean to a particular harmonic of the forcing term that takes the form [see Equation (12.143)]

, of the ocean to a particular harmonic of the forcing term that takes the form [see Equation (12.143)]

![$\displaystyle = - \frac{f_j\,n\,(n+1)\,(n-m_j-1)\,(n-m_j)}{(2\,n-3)\,(2\,n-1)\,[m_j-n\,(n-1)\,f_j]},$](img4701.png)

![$\displaystyle = \frac{n\,(n+1)}{\beta}\left(1-[1+k_n'-h_n']\,\alpha_n\right) + \frac{m_j\,f_j}{n\,(n+1)}-f_j^{\,2}$](img4703.png)

![$\displaystyle \phantom{=}- \frac{f_j\,(n-1)^2\,(n+1)\,(n-m_j)\,(n+m_j)}{n\,(2\,n-1)\,(2\,n+1)\,[m_j-n\,(n-1)\,f_j]}$](img4704.png)

![$\displaystyle \phantom{=}-\frac{f_j\,(n+2)^2\,n\,(n-m_j+1)\,(n+m_j+1)}{(n+1)\,(2\,n+1)\,(2\,n+3)\,[m_j-(n+1)\,(n+2)\,f_j]},$](img4705.png)

![$\displaystyle =-\frac{f_j\,n\,(n+1)\,(n+m_j+1)\,(n+m_j+2)}{(2\,n+3)\,(2\,n+5)\,[m_j-(n+1)\,(n+2)\,f_j]}.$](img4707.png)

![]() th tidal harmonic in terms of the function

th tidal harmonic in terms of the function

![]() ,

which is defined such that

,

which is defined such that

![$\displaystyle \skew{5}\hat{\zeta}_j(\vartheta)= \left[\frac{1+k_2-h_2}{1-(1+k_2'-h_2')\,\alpha_2}\right]\skew{5}\tilde{\zeta}_j\,P_2^{\,m_j}(\sin\vartheta).$](img4719.png)

![]() times lower than those of the equilibrium tides. The

times lower than those of the equilibrium tides. The ![]() (

(![]() ) and

) and

![]() (

(![]() ) solutions cause a slight increase in the equatorial bulge of the Earth's oceans when the Sun and Moon, respectively, pass through the equinoxes,

and a slight reduction when they pass through the solstices. The

) solutions cause a slight increase in the equatorial bulge of the Earth's oceans when the Sun and Moon, respectively, pass through the equinoxes,

and a slight reduction when they pass through the solstices. The ![]() (

(![]() ) solution causes a slight increase in the equatorial bulge of the Earth's oceans when the Moon

passes through its perigee, and a slight reduction when it passes through its apogee.

) solution causes a slight increase in the equatorial bulge of the Earth's oceans when the Moon

passes through its perigee, and a slight reduction when it passes through its apogee.

![]() solution is about

solution is about ![]() times lower than that of the

times lower than that of the ![]() equilibrium tide. The amplitudes of the

equilibrium tide. The amplitudes of the ![]() and

and ![]() solutions are negligibly small. (In fact,

the amplitude of the

solutions are negligibly small. (In fact,

the amplitude of the ![]() solution is identically zero.) The

solution is identically zero.) The ![]() (

(![]() ) solution causes the Earth's oceans to displace slightly toward the Moon when it passes

through the equinoxes, and away from the Moon when it passes through the solstices.

) solution causes the Earth's oceans to displace slightly toward the Moon when it passes

through the equinoxes, and away from the Moon when it passes through the solstices.

![]() (

(![]() ) solution generates a high tide

at a particular point on the Earth's surface every

) solution generates a high tide

at a particular point on the Earth's surface every ![]() hours. The

hours. The ![]() (

(![]() ) solution causes an enhancement of the high tide--a so-called spring tide--at the new and

full moons (i.e., every half a synodic month, or

) solution causes an enhancement of the high tide--a so-called spring tide--at the new and

full moons (i.e., every half a synodic month, or ![]() days). Finally, the

days). Finally, the ![]() (

(![]() ) solution causes an enhancement of the spring tide--a so-called perigean spring tide--whenever the new or full moon coincides with the passage of the moon through its perigee.

) solution causes an enhancement of the spring tide--a so-called perigean spring tide--whenever the new or full moon coincides with the passage of the moon through its perigee.

![]() tide, this

implies that, at a given point on the Earth's surface, there should be either a tidal maximum or a tidal minimum whenever the Moon culminates.

It turns out that this is not the case (Cartwright 1999). Indeed, the observed phase difference between the

tide, this

implies that, at a given point on the Earth's surface, there should be either a tidal maximum or a tidal minimum whenever the Moon culminates.

It turns out that this is not the case (Cartwright 1999). Indeed, the observed phase difference between the ![]() tide and the corresponding

equilibrium tide varies from place to place on the Earth's surface, and can take any value. In other words, high tide at a given point on the Earth can

occur three hours before the Moon culminates, or two hours after, et cetera, and the time lag between high tide and the culmination of the Moon

varies from place to place.

We conjecture that this effect is caused by the

continents impeding the flow of tidal waves around the Earth. Hence, we now need to consider tides in oceans that do not

cover the whole surface of the Earth.

tide and the corresponding

equilibrium tide varies from place to place on the Earth's surface, and can take any value. In other words, high tide at a given point on the Earth can

occur three hours before the Moon culminates, or two hours after, et cetera, and the time lag between high tide and the culmination of the Moon

varies from place to place.

We conjecture that this effect is caused by the

continents impeding the flow of tidal waves around the Earth. Hence, we now need to consider tides in oceans that do not

cover the whole surface of the Earth.