Next: Gravity Waves in a

Up: Waves in Incompressible Fluids

Previous: Wave Drag on Ships

Ship Wakes

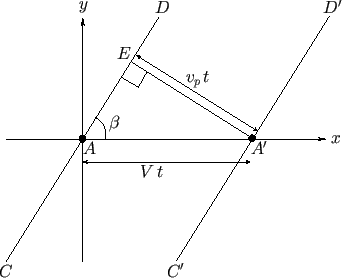

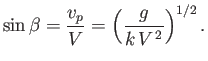

Let us now make a detailed investigation of the wake pattern generated behind a ship as it travels over a body of water, taking

into account obliquely propagating gravity waves, in addition to transverse waves. For the sake of simplicity, the finite length of the ship

is neglected in the following analysis. In other words, the ship is treated as a point source of gravity waves. Consider Figure 11.3. This shows

a plane gravity wave generated on the surface of the water by a moving ship. The water surface corresponds to the  -

- plane. The

ship is traveling along the

plane. The

ship is traveling along the  -axis, in the negative

-axis, in the negative  -direction, at the constant speed

-direction, at the constant speed  . Suppose that the ship's bow is initially at point

. Suppose that the ship's bow is initially at point  ,

and has moved to point

,

and has moved to point  after a time interval

after a time interval  . The only type of gravity wave that is continuously excited by the passage of the ship

is one that maintains a constant phase relation with respect to its bow. In fact, as we have already mentioned, the bow should always correspond to a wave maximum.

An oblique wavefront associated with such a wave is shown in the figure. Here, the wavefront

. The only type of gravity wave that is continuously excited by the passage of the ship

is one that maintains a constant phase relation with respect to its bow. In fact, as we have already mentioned, the bow should always correspond to a wave maximum.

An oblique wavefront associated with such a wave is shown in the figure. Here, the wavefront  , which initially passes through the bow at point

, which initially passes through the bow at point  , has moved

to

, has moved

to  after a time interval

after a time interval  , such that it again passes through the bow at point

, such that it again passes through the bow at point  . Of course, the wavefront propagates at the

phase velocity,

. Of course, the wavefront propagates at the

phase velocity,  . It follows that, in the right-angled triangle

. It follows that, in the right-angled triangle  , the sides

, the sides  and

and  are of lengths

are of lengths  and

and  , respectively,

so that

, respectively,

so that

|

(11.67) |

This, therefore, is the condition that must be satisfied in order for an obliquely propagating gravity wave to maintain a constant phase relation with respect to the ship.

Figure 11.3:

An oblique plane wave generated on the surface of the water by a moving ship.

|

In shallow water, all gravity waves propagate at the same phase velocity: that is,

|

(11.68) |

where  is the water depth. Hence, Equation (11.67) yields

is the water depth. Hence, Equation (11.67) yields

![$\displaystyle \beta = \sin^{-1}\left[\frac{(g\,d)^{1/2}}{V}\right].$](img4018.png) |

(11.69) |

This equation can only be satisfied when

|

(11.70) |

In other words, the ship must be traveling faster than the critical speed

.

Moreover, if this is the case then there is only one value of

.

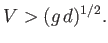

Moreover, if this is the case then there is only one value of  that satisfies Equation (11.69). This implies the scenario illustrated in

Figure 11.4. Here, the ship is instantaneously at

that satisfies Equation (11.69). This implies the scenario illustrated in

Figure 11.4. Here, the ship is instantaneously at  , and the wave maxima that it previously generated--which all

propagate obliquely, subtending a fixed angle

, and the wave maxima that it previously generated--which all

propagate obliquely, subtending a fixed angle  with the

with the  -axis--have interfered constructively

to produce a single strong wave maximum

-axis--have interfered constructively

to produce a single strong wave maximum  . In fact, the wave maxima generated when the ship was at

. In fact, the wave maxima generated when the ship was at  have travelled to

have travelled to

and

and  , the wave maxima generated when the ship was at

, the wave maxima generated when the ship was at  have travelled to

have travelled to  and

and  , et cetera. We conclude

that a ship traveling over shallow water produces a V-shaped wake whose semi-angle,

, et cetera. We conclude

that a ship traveling over shallow water produces a V-shaped wake whose semi-angle,  , is determined by the ship's speed.

Indeed, as is apparent from Equation (11.69), the faster the ship travels over the water, the smaller the angle

, is determined by the ship's speed.

Indeed, as is apparent from Equation (11.69), the faster the ship travels over the water, the smaller the angle  becomes.

Shallow water wakes are especially dangerous to other vessels, and particularly destructive of the coastline, because all

of the wave energy produced by the ship is concentrated into a single large wave maximum. Note, finally, that the wake

contains no transverse waves, because, as we have already mentioned, such waves cannot keep up with a ship

traveling faster than the critical speed

becomes.

Shallow water wakes are especially dangerous to other vessels, and particularly destructive of the coastline, because all

of the wave energy produced by the ship is concentrated into a single large wave maximum. Note, finally, that the wake

contains no transverse waves, because, as we have already mentioned, such waves cannot keep up with a ship

traveling faster than the critical speed

.

.

Figure 11.4:

A shallow water wake.

|

Let us now discuss the wake generated by a ship traveling over deep water. In this case, the phase velocity of

gravity waves is

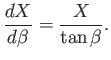

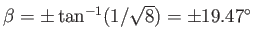

. Thus, Equation (11.67) yields

. Thus, Equation (11.67) yields

|

(11.71) |

It follows that in deep water any obliquely propagating gravity wave whose wave number exceeds the critical value

|

(11.72) |

can keep up with the ship, as long as its direction of propagation is such that Equation (11.71) is satisfied. In other words, the

ship continuously excites gravity waves with a wide range of different wave numbers and propagation directions. The

wake is essentially the interference pattern generated by these waves. As is well known (Fitzpatrick 2013), an interference maximum

generated by the superposition of plane waves with a range of different wave numbers propagates at the group velocity,  .

Furthermore, as we have already seen, the group velocity of deep water gravity waves is half their phase velocity: that is,

.

Furthermore, as we have already seen, the group velocity of deep water gravity waves is half their phase velocity: that is,  .

.

Figure 11.5:

Formation of an interference maximum in a deep water wake.

|

Consider Figure 11.5. The curve  corresponds to a particular interference maximum in the wake. Here,

corresponds to a particular interference maximum in the wake. Here,  is

the ship's instantaneous position. Consider a point

is

the ship's instantaneous position. Consider a point  on this curve. Let

on this curve. Let  and

and  be the coordinates of this point, relative to the

ship. The interference maximum at

be the coordinates of this point, relative to the

ship. The interference maximum at  is part of the plane wavefront

is part of the plane wavefront  emitted some time

emitted some time  earlier, when the ship was at point

earlier, when the ship was at point  .

Let

.

Let  be the angle subtended between this wavefront and the

be the angle subtended between this wavefront and the  -axis.

Because interference maxima propagate at the group velocity, the distance

-axis.

Because interference maxima propagate at the group velocity, the distance  is equal to

is equal to  . Of course, the distance

. Of course, the distance  is

equal to

is

equal to  . Simple trigonometry reveals that

. Simple trigonometry reveals that

Moreover,

|

(11.75) |

because  is the tangent to the curve

is the tangent to the curve  --that is, the curve

--that is, the curve  --at point

--at point  . It follows from Equation (11.71), and the fact that

. It follows from Equation (11.71), and the fact that  , that

, that

where

. The previous three equations can be combined to produce

. The previous three equations can be combined to produce

which reduces to

|

(11.79) |

This expression can be solved to give

|

(11.80) |

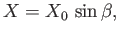

where  is a constant. Hence, the locus of our interference maximum is determined parametrically by

is a constant. Hence, the locus of our interference maximum is determined parametrically by

Here, the angle  ranges

from

ranges

from  to

to  .

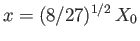

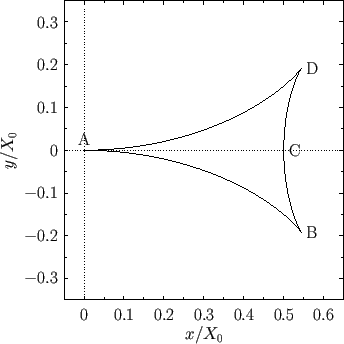

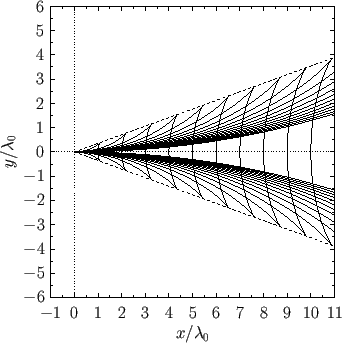

The curve specified by the previous equations is plotted in Figure 11.6. As usual,

.

The curve specified by the previous equations is plotted in Figure 11.6. As usual,  is the instantaneous

position of the ship. It can be seen that the interference maximum essentially consists of the transverse maximum

is the instantaneous

position of the ship. It can be seen that the interference maximum essentially consists of the transverse maximum  , and the two radial maxima

, and the two radial maxima  and

and  . As is easily demonstrated, point

. As is easily demonstrated, point  , which corresponds to

, which corresponds to  , lies at

, lies at  ,

,  . Moreover, the

two cusps,

. Moreover, the

two cusps,  and

and  , which correspond to

, which correspond to

, lie at

, lie at

,

,

.

.

Figure 11.6:

Locus of an interference maximum in a deep water wake.

|

The complete interference pattern that constitutes the wake is constructed out of many different wave maximum curves of the form shown in Figure 11.6, corresponding to

many different values of the parameter  . However, these

. However, these  values must be chosen such that the wavelength of the pattern

along the

values must be chosen such that the wavelength of the pattern

along the  -axis corresponds to the wavelength

-axis corresponds to the wavelength

of transverse (i.e.,

of transverse (i.e.,  ) gravity waves whose

phase velocity matches the speed of the ship. This implies that

) gravity waves whose

phase velocity matches the speed of the ship. This implies that

, where

, where  is a positive integer. A complete deep water wake pattern is

shown in Figure 11.7. This pattern, which is made up of interlocking transverse and radial wave maxima, fills a wedge-shaped region--known

as a Kelvin wedge--whose semi-angle takes the value

is a positive integer. A complete deep water wake pattern is

shown in Figure 11.7. This pattern, which is made up of interlocking transverse and radial wave maxima, fills a wedge-shaped region--known

as a Kelvin wedge--whose semi-angle takes the value

. This angle is independent of the ship's speed. Finally, our initial assumption that the gravity waves that form

the wake are all deep water waves is valid provided

. This angle is independent of the ship's speed. Finally, our initial assumption that the gravity waves that form

the wake are all deep water waves is valid provided

, which implies that

, which implies that

|

(11.83) |

In other words, the ship must travel at a speed that is much less than the critical speed

. This explains why the

wake contains transverse wave maxima.

. This explains why the

wake contains transverse wave maxima.

Figure 11.7:

A deep water wake.

|

Next: Gravity Waves in a

Up: Waves in Incompressible Fluids

Previous: Wave Drag on Ships

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-03-31

![]() . Thus, Equation (11.67) yields

. Thus, Equation (11.67) yields

![]() corresponds to a particular interference maximum in the wake. Here,

corresponds to a particular interference maximum in the wake. Here, ![]() is

the ship's instantaneous position. Consider a point

is

the ship's instantaneous position. Consider a point ![]() on this curve. Let

on this curve. Let ![]() and

and ![]() be the coordinates of this point, relative to the

ship. The interference maximum at

be the coordinates of this point, relative to the

ship. The interference maximum at ![]() is part of the plane wavefront

is part of the plane wavefront ![]() emitted some time

emitted some time ![]() earlier, when the ship was at point

earlier, when the ship was at point ![]() .

Let

.

Let ![]() be the angle subtended between this wavefront and the

be the angle subtended between this wavefront and the ![]() -axis.

Because interference maxima propagate at the group velocity, the distance

-axis.

Because interference maxima propagate at the group velocity, the distance ![]() is equal to

is equal to ![]() . Of course, the distance

. Of course, the distance ![]() is

equal to

is

equal to ![]() . Simple trigonometry reveals that

. Simple trigonometry reveals that

![$\displaystyle =\frac{dy/d\beta}{dx/d\beta} = \frac{(1/2)\,dX/d\beta\,\sin\beta\...

...\beta-\sin^2\beta)} {dX/d\beta\,[1-(1/2)\,\sin^2\beta]-X\,\sin\beta\,\cos\beta}$](img4042.png)

![]() . However, these

. However, these ![]() values must be chosen such that the wavelength of the pattern

along the

values must be chosen such that the wavelength of the pattern

along the ![]() -axis corresponds to the wavelength

-axis corresponds to the wavelength

![]() of transverse (i.e.,

of transverse (i.e., ![]() ) gravity waves whose

phase velocity matches the speed of the ship. This implies that

) gravity waves whose

phase velocity matches the speed of the ship. This implies that

![]() , where

, where ![]() is a positive integer. A complete deep water wake pattern is

shown in Figure 11.7. This pattern, which is made up of interlocking transverse and radial wave maxima, fills a wedge-shaped region--known

as a Kelvin wedge--whose semi-angle takes the value

is a positive integer. A complete deep water wake pattern is

shown in Figure 11.7. This pattern, which is made up of interlocking transverse and radial wave maxima, fills a wedge-shaped region--known

as a Kelvin wedge--whose semi-angle takes the value

![]() . This angle is independent of the ship's speed. Finally, our initial assumption that the gravity waves that form

the wake are all deep water waves is valid provided

. This angle is independent of the ship's speed. Finally, our initial assumption that the gravity waves that form

the wake are all deep water waves is valid provided

![]() , which implies that

, which implies that