Next: Basins of attraction

Up: The chaotic pendulum

Previous: The Poincaré section

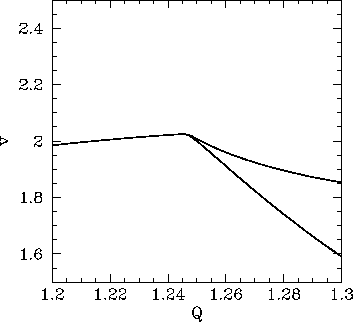

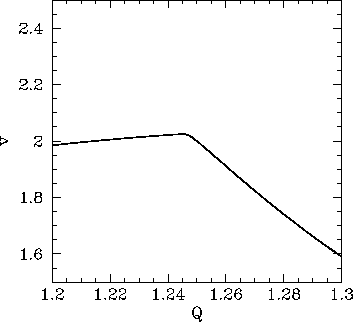

Figure 30:

The  -coordinate of the Poincaré section of a time-asymptotic orbit

plotted against the quality-factor

-coordinate of the Poincaré section of a time-asymptotic orbit

plotted against the quality-factor  . Data

calculated numerically for

. Data

calculated numerically for

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

, and

, and  .

.

|

Suppose that we now gradually increase the quality-factor  . What happens to the

simple orbit shown in Fig. 28? It turns out that, at first, nothing particularly exciting

happens. The size of the orbit gradually increases, indicating a corresponding increase in

the amplitude of the pendulum's motion, but the general nature of the motion remains unchanged.

However, something interesting does occur when

. What happens to the

simple orbit shown in Fig. 28? It turns out that, at first, nothing particularly exciting

happens. The size of the orbit gradually increases, indicating a corresponding increase in

the amplitude of the pendulum's motion, but the general nature of the motion remains unchanged.

However, something interesting does occur when  is increased beyond about

is increased beyond about  .

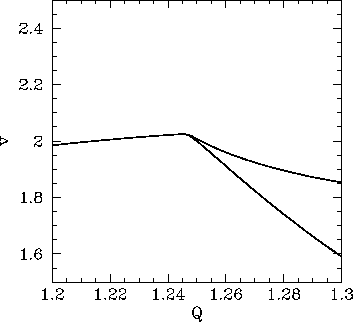

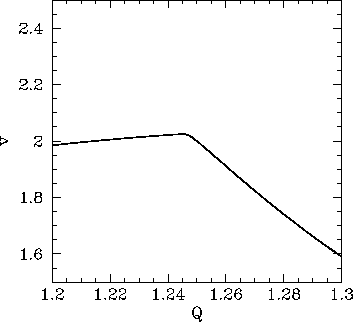

Figure 30 shows the

.

Figure 30 shows the  -coordinate of the orbit's Poincaré section plotted

against

-coordinate of the orbit's Poincaré section plotted

against  in the range

in the range  and

and  . Note the sharp downturn

in the curve at

. Note the sharp downturn

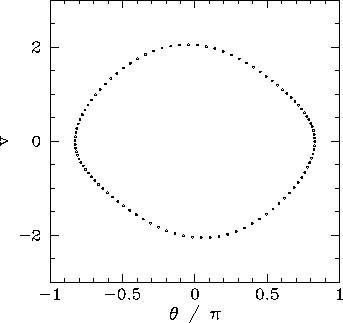

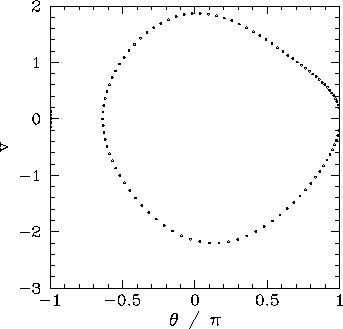

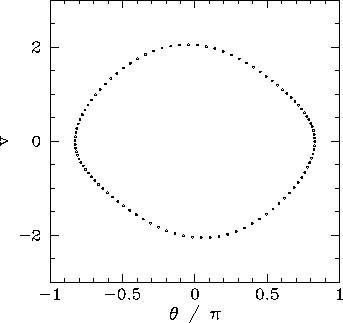

in the curve at  . What does this signify? Well, Fig. 31 shows

the time-asymptotic phase-space orbit just before the downturn (i.e.,

at

. What does this signify? Well, Fig. 31 shows

the time-asymptotic phase-space orbit just before the downturn (i.e.,

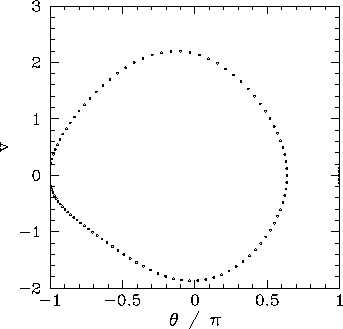

at  ), and Fig. 32 shows the orbit somewhat after the downturn

(i.e., at

), and Fig. 32 shows the orbit somewhat after the downturn

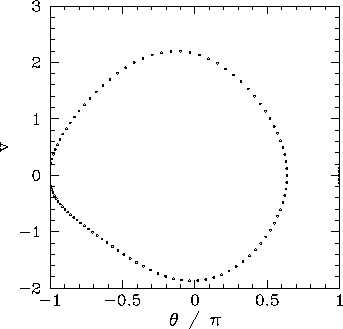

(i.e., at  ). It is clear that the downturn is associated with a

sudden change in the nature of the pendulum's time-asymptotic phase-space orbit. Prior to the downturn, the orbit

spends as much time in the region

). It is clear that the downturn is associated with a

sudden change in the nature of the pendulum's time-asymptotic phase-space orbit. Prior to the downturn, the orbit

spends as much time in the region  as in the region

as in the region  . However,

after the downturn the orbit spends the majority of its time in the region

. However,

after the downturn the orbit spends the majority of its time in the region  .

In other words, after the downturn the pendulum bob favours the region to the left of

the pendulum's vertical. This is somewhat surprising, since there is nothing in the

pendulum's equations of motion which differentiates between the regions to the left

and to the right of the vertical. We refer to a solution of this type--which fails

to realize the full symmetry of the dynamical system in question--as a symmetry

breaking solution. In this case, because the particular symmetry which is broken is

a spatial symmetry, we refer to the process by which the symmetry breaking solution

suddenly appears, as the control parameter

.

In other words, after the downturn the pendulum bob favours the region to the left of

the pendulum's vertical. This is somewhat surprising, since there is nothing in the

pendulum's equations of motion which differentiates between the regions to the left

and to the right of the vertical. We refer to a solution of this type--which fails

to realize the full symmetry of the dynamical system in question--as a symmetry

breaking solution. In this case, because the particular symmetry which is broken is

a spatial symmetry, we refer to the process by which the symmetry breaking solution

suddenly appears, as the control parameter  is adjusted, as spatial symmetry breaking.

Needless to say, spatial symmetry breaking is an intrinsically non-linear process--it

cannot take place in dynamical systems possessing linear equations of motion.

is adjusted, as spatial symmetry breaking.

Needless to say, spatial symmetry breaking is an intrinsically non-linear process--it

cannot take place in dynamical systems possessing linear equations of motion.

Figure 31:

Equally spaced (in time) points on a time-asymptotic orbit in phase-space.

Data calculated numerically for  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

, and

, and

.

.

|

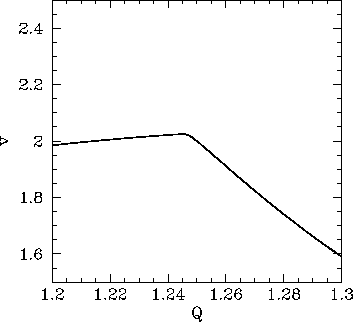

Figure 32:

Equally spaced (in time) points on a time-asymptotic orbit in phase-space.

Data calculated

numerically for  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

, and

, and

.

.

|

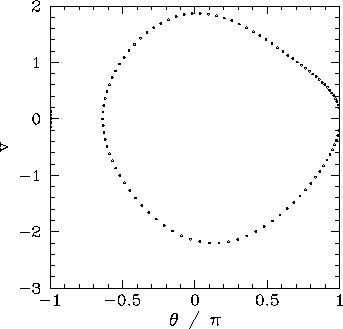

It stands to reason that since the pendulum's equations of motion favour neither the

left nor the right then the left-favouring orbit pictured in Fig. 32 must be accompanied

by a mirror image right-favouring orbit. How do we obtain this mirror image orbit?

It turns out that all we have to do is keep the physics parameters  ,

,  , and

, and  fixed, but change the initial conditions

fixed, but change the initial conditions  and

and  . Figure 33 shows

a time-asymptotic phase-space orbit calculated with the same physics parameters used in Fig. 32, but

with the initial conditions

. Figure 33 shows

a time-asymptotic phase-space orbit calculated with the same physics parameters used in Fig. 32, but

with the initial conditions  and

and  , instead of

, instead of  and

and

. It can be seen that the orbit is indeed the mirror image of that pictured in Fig. 32.

. It can be seen that the orbit is indeed the mirror image of that pictured in Fig. 32.

Figure 33:

Equally spaced (in time) points on a time-asymptotic orbit in phase-space. Data

calculated numerically for  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

, and

, and

.

.

|

Figure 34 shows the  -coordinate of the Poincaré section of a time-asymptotic orbit,

calculated with the same physics parameters used in Fig. 30, versus

-coordinate of the Poincaré section of a time-asymptotic orbit,

calculated with the same physics parameters used in Fig. 30, versus

in the range

in the range  and

and  . Data is shown for the two sets of

initial conditions discussed above. The figure is interpreted as

follows. When

. Data is shown for the two sets of

initial conditions discussed above. The figure is interpreted as

follows. When  is less than a critical value,

which is about

is less than a critical value,

which is about  , then the two sets of initial conditions lead to motions

which converge on the same, left-right symmetric,

period-1 attractor. However, once

, then the two sets of initial conditions lead to motions

which converge on the same, left-right symmetric,

period-1 attractor. However, once

exceeds the critical value then the attractor bifurcates into two

asymmetric, mirror image, period-1

attractors. Obviously, the bifurcation is indicated by the forking of the

curve shown in Fig. 34. The lower and upper branches correspond to the left- and right-favouring

attractors, respectively.

exceeds the critical value then the attractor bifurcates into two

asymmetric, mirror image, period-1

attractors. Obviously, the bifurcation is indicated by the forking of the

curve shown in Fig. 34. The lower and upper branches correspond to the left- and right-favouring

attractors, respectively.

Figure 34:

The  -coordinate of the Poincaré section of a time-asymptotic orbit

plotted against the quality-factor

-coordinate of the Poincaré section of a time-asymptotic orbit

plotted against the quality-factor  . Data

calculated numerically for

. Data

calculated numerically for

,

,  , and

, and

. Data is shown for two sets of initial

conditions:

. Data is shown for two sets of initial

conditions:  and

and  (lower branch); and

(lower branch); and  and

and  (upper branch).

(upper branch).

|

Spontaneous symmetry breaking, which is the fundamental non-linear process illustrated in the

above discussion, plays an

important role in many areas of physics. For instance, symmetry breaking gives mass

to elementary particles in the unified theory of electromagnetic and weak interactions.25Symmetry breaking also plays a pivotal role in the so-called ``inflation'' theory of the expansion

of the early universe.26

Next: Basins of attraction

Up: The chaotic pendulum

Previous: The Poincaré section

Richard Fitzpatrick

2006-03-29

![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() fixed, but change the initial conditions

fixed, but change the initial conditions ![]() and

and ![]() . Figure 33 shows

a time-asymptotic phase-space orbit calculated with the same physics parameters used in Fig. 32, but

with the initial conditions

. Figure 33 shows

a time-asymptotic phase-space orbit calculated with the same physics parameters used in Fig. 32, but

with the initial conditions ![]() and

and ![]() , instead of

, instead of ![]() and

and

![]() . It can be seen that the orbit is indeed the mirror image of that pictured in Fig. 32.

. It can be seen that the orbit is indeed the mirror image of that pictured in Fig. 32.

![]() -coordinate of the Poincaré section of a time-asymptotic orbit,

calculated with the same physics parameters used in Fig. 30, versus

-coordinate of the Poincaré section of a time-asymptotic orbit,

calculated with the same physics parameters used in Fig. 30, versus

![]() in the range

in the range ![]() and

and ![]() . Data is shown for the two sets of

initial conditions discussed above. The figure is interpreted as

follows. When

. Data is shown for the two sets of

initial conditions discussed above. The figure is interpreted as

follows. When ![]() is less than a critical value,

which is about

is less than a critical value,

which is about ![]() , then the two sets of initial conditions lead to motions

which converge on the same, left-right symmetric,

period-1 attractor. However, once

, then the two sets of initial conditions lead to motions

which converge on the same, left-right symmetric,

period-1 attractor. However, once

![]() exceeds the critical value then the attractor bifurcates into two

asymmetric, mirror image, period-1

attractors. Obviously, the bifurcation is indicated by the forking of the

curve shown in Fig. 34. The lower and upper branches correspond to the left- and right-favouring

attractors, respectively.

exceeds the critical value then the attractor bifurcates into two

asymmetric, mirror image, period-1

attractors. Obviously, the bifurcation is indicated by the forking of the

curve shown in Fig. 34. The lower and upper branches correspond to the left- and right-favouring

attractors, respectively.