Gravity Waves

Consider a stationary body of water, of uniform depth  , located on the surface of the Earth. Let us

find the dispersion relation of a plane wave propagating across the water's surface. Suppose that the Cartesian coordinate

, located on the surface of the Earth. Let us

find the dispersion relation of a plane wave propagating across the water's surface. Suppose that the Cartesian coordinate  measures horizontal distance,

while the coordinate

measures horizontal distance,

while the coordinate  measures vertical height, with

measures vertical height, with  corresponding to the unperturbed surface of the water.

Let there be no variation in the

corresponding to the unperturbed surface of the water.

Let there be no variation in the  -direction. In other words, let the wavefronts of the wave all be parallel to the

-direction. In other words, let the wavefronts of the wave all be parallel to the  -axis. Finally, let

-axis. Finally, let

and

and

be the perturbed horizontal and

vertical velocity fields of the water due to the wave. It is assumed that there is no

motion in the

be the perturbed horizontal and

vertical velocity fields of the water due to the wave. It is assumed that there is no

motion in the  -direction.

-direction.

Water is essentially incompressible (i.e., its bulk modulus is very large) (Batchelor 2000). Thus, any (low speed) wave disturbance in water is

constrained to preserve the volume of a co-moving volume element. Equivalently, the inflow rate of water into a stationary volume element must match the outflow rate.

Consider a stationary

cubic volume element lying between  and

and  ,

,  and

and  , and

, and  and

and  . The element has two faces, of area

. The element has two faces, of area  , perpendicular to the

, perpendicular to the  -axis, located at

-axis, located at

and

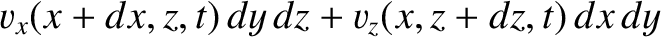

and  . Water flows into the element through the former face

at the rate

. Water flows into the element through the former face

at the rate

(i.e., the product of the area of the face and the

normal velocity), and out of the element though the

latter face at the rate

(i.e., the product of the area of the face and the

normal velocity), and out of the element though the

latter face at the rate

. The element also has two

faces perpendicular to the

. The element also has two

faces perpendicular to the  -axis, but there is no flow through these faces, because

-axis, but there is no flow through these faces, because

. Finally, the element has two faces, of area

. Finally, the element has two faces, of area  , perpendicular to the

, perpendicular to the  -axis, located at

-axis, located at

and

and  . Water flows into the element through the former face

at the rate

. Water flows into the element through the former face

at the rate

, and out of the element though the

latter face at the rate

, and out of the element though the

latter face at the rate

.

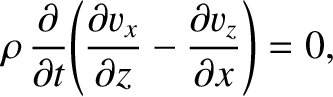

Thus, the net rate at which water flows into the element is

.

Thus, the net rate at which water flows into the element is

.

Likewise, the net rate at which water flows out of the element is

.

Likewise, the net rate at which water flows out of the element is

. If the water is to remain incompressible

then the inflow and outflow rates must match. In other words,

. If the water is to remain incompressible

then the inflow and outflow rates must match. In other words,

|

(9.258) |

or

![$\displaystyle \left[\frac{v_x(x+dx,z,t)-v_x(x,z,t)}{dx} + \frac{v_z(x,z+dz,t)-v_z(x,z,t)}{dz} \right]dx\,dy\,dz=0.$](img3003.png) |

(9.259) |

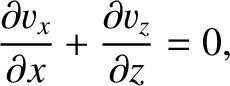

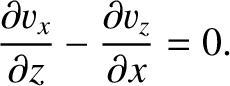

Hence, the incompressibility constraint reduces to

|

(9.260) |

which is consistent with Equation (7.194) in the incompressible limit

.9.1 Incidentally,

it is reasonable to neglect the finite compressibility of water in this investigation because sound waves (which require finite compressibility)

propagate much faster than surface waves, and, therefore, do not couple to them. (See the two footnotes in this section.)

.9.1 Incidentally,

it is reasonable to neglect the finite compressibility of water in this investigation because sound waves (which require finite compressibility)

propagate much faster than surface waves, and, therefore, do not couple to them. (See the two footnotes in this section.)

Consider the equation of motion of a small volume element of water lying between  and

and  ,

,  and

and  , and

, and  and

and  . The mass of this element is

. The mass of this element is

, where

, where

is the uniform mass density of water. Suppose

that

is the uniform mass density of water. Suppose

that  is the pressure in the water, which is assumed to be isotropic (Batchelor 2000).

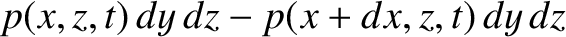

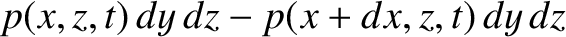

The net horizontal force on the element is

is the pressure in the water, which is assumed to be isotropic (Batchelor 2000).

The net horizontal force on the element is

(because force is pressure times area, and the external pressure forces

acting on the element are directed inward normal to its surface). Hence, the element's horizontal equation of motion is

(because force is pressure times area, and the external pressure forces

acting on the element are directed inward normal to its surface). Hence, the element's horizontal equation of motion is

![$\displaystyle \rho\,dx\,dy\,dz\,\frac{\partial v_x(x,z,t)}{\partial t} = -\left[\frac{p(x+dx,z,t)-p(x,z,t)}{dx}\right]dx\,dy\,dz,$](img3013.png) |

(9.261) |

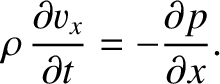

which reduces to

|

(9.262) |

[See Equation (7.192).]

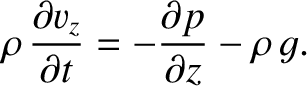

The vertical equation of motion is similar, except that the element is subject to

a downward acceleration,

, due to gravity. Hence, we obtain

, due to gravity. Hence, we obtain

|

(9.263) |

[See Equation (7.193).]

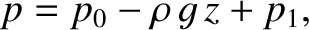

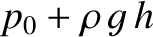

We can write

|

(9.264) |

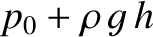

where  is atmospheric pressure (i.e., the air pressure just above the surface of the water), and

is atmospheric pressure (i.e., the air pressure just above the surface of the water), and  is the pressure perturbation due to the wave. In the absence of

the wave, the water pressure at a depth

is the pressure perturbation due to the wave. In the absence of

the wave, the water pressure at a depth  below the surface is

below the surface is

(Batchelor 2000).

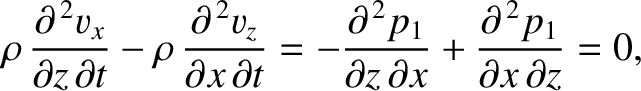

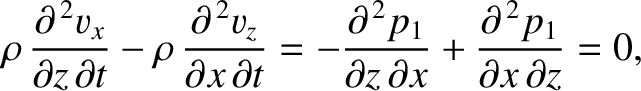

Substitution into Equations (9.262) and (9.263) yields

It follows that

(Batchelor 2000).

Substitution into Equations (9.262) and (9.263) yields

It follows that

|

(9.267) |

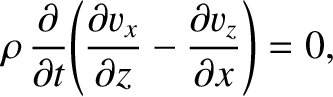

which implies that

|

(9.268) |

or

|

(9.269) |

(Actually, this quantity could be non-zero and constant in time, but this is

not consistent with an oscillating wave-like solution.)

Equation (9.269) is automatically satisfied by writing the fluid velocity in terms of a velocity potential; that is,

(See Section 7.12.)

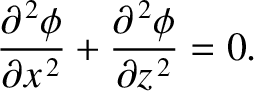

Equation (9.260) then gives 9.2

|

(9.272) |

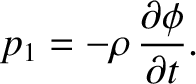

Finally, Equations (9.265) and (9.266) yield

|

(9.273) |

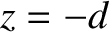

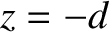

As we have just demonstrated, surface waves in water are governed by Equation (9.272),

which is known as Laplace's equation. We now need to derive the physical

constraints that must be satisfied by the solution to this equation at

the water's upper and lower boundaries. The water is bounded from below by a

solid surface located at  . Assuming that the water always remains in contact

with this surface, the appropriate physical constraint at the lower boundary is

. Assuming that the water always remains in contact

with this surface, the appropriate physical constraint at the lower boundary is

(i.e., there is no vertical motion of the water at the lower boundary), or

(i.e., there is no vertical motion of the water at the lower boundary), or

|

(9.274) |

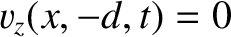

The physical constraint at the water's upper boundary is a little more complicated, because this boundary is a free surface.

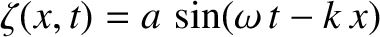

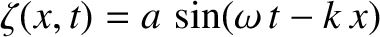

Let

represent the vertical displacement of the water's surface. It

follows that

represent the vertical displacement of the water's surface. It

follows that

|

(9.275) |

The physical constraint at the surface is that the water pressure is equal to atmospheric pressure, because there cannot be a pressure discontinuity across a free surface (in the absence of surface tension).

Thus, it follows from Equation (9.264) that

|

(9.276) |

Finally, differentiating with respect to  , and making use of Equations (9.273) and (9.275), we obtain

, and making use of Equations (9.273) and (9.275), we obtain

|

(9.277) |

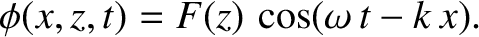

Hence, the problem boils down to solving Laplace's equation, (9.272), subject

to the physical constraints (9.274) and (9.277).

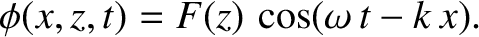

Let us search for a propagating wave-like solution of Equation (9.272) of the form

|

(9.278) |

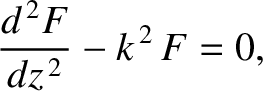

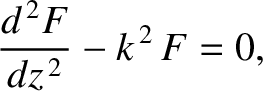

Substitution into Equation (9.272) yields

|

(9.279) |

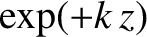

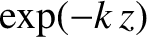

whose independent solutions are

and

and

.

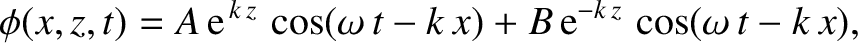

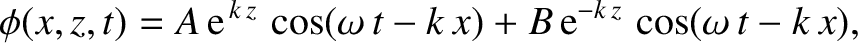

Hence, the most general wave-like solution to Laplace's equation is

.

Hence, the most general wave-like solution to Laplace's equation is

|

(9.280) |

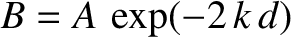

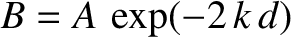

where  and

and  are arbitrary constants. The boundary condition (9.274)

is satisfied provided that

are arbitrary constants. The boundary condition (9.274)

is satisfied provided that

, giving

, giving

![$\displaystyle \phi(x,z,t) = A\left[{\rm e}^{\,k\,z}\ + {\rm e}^{-k\,(z+2\,d)}\right]\cos(\omega\,t-k\,x),$](img3044.png) |

(9.281) |

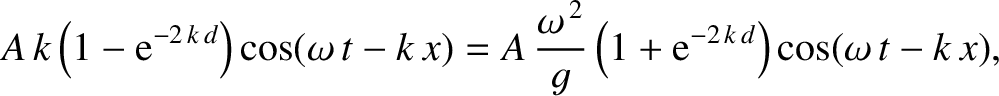

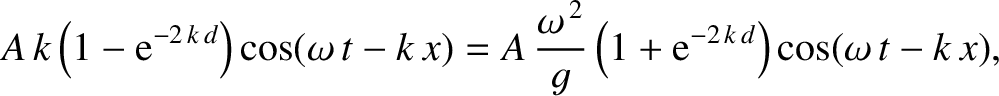

The boundary condition (9.277) yields

|

(9.282) |

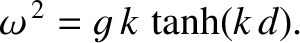

which reduces to the dispersion relation

|

(9.283) |

The type of wave just described is generally known

as a gravity wave.

We conclude that a gravity wave of arbitrary wavenumber  , propagating horizontally through water of depth

, propagating horizontally through water of depth  , has a phase velocity

, has a phase velocity

![$\displaystyle v_p = \frac{\omega}{k}=(g\,d)^{1/2}\left[\frac{\tanh(k\,d)}{k\,d}\right]^{1/2}.$](img3047.png) |

(9.284) |

Moreover, the ratio of the group to the phase velocity is

![$\displaystyle \frac{v_g}{v_p} =\frac{k}{\omega}\,\frac{d\omega}{dk}=\frac{1}{2}\left[1+\frac{2\,k\,d}{\sinh(2\,k\,d)}\right].$](img3048.png) |

(9.285) |

Finally, the

velocity fields associated with a gravity wave of surface amplitude  are

are

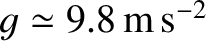

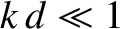

In shallow water (i.e.,  ), Equation (9.283) reduces to

the linear dispersion relation

), Equation (9.283) reduces to

the linear dispersion relation

|

(9.288) |

Here, use has been made of the small argument expansion

for

for  . (See Appendix B.)

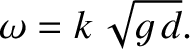

It follows that gravity waves in shallow water are non-dispersive in nature, and

propagate at the phase velocity

. (See Appendix B.)

It follows that gravity waves in shallow water are non-dispersive in nature, and

propagate at the phase velocity

. On the other hand, in deep water (i.e.,

. On the other hand, in deep water (i.e.,  ), Equation (9.283) reduces to

the nonlinear dispersion relation

), Equation (9.283) reduces to

the nonlinear dispersion relation

|

(9.289) |

Here, use has been made of the large argument expansion

for

for  .

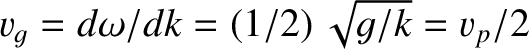

We conclude that gravity waves in deep water are dispersive in nature. The

phase velocity of the waves is

.

We conclude that gravity waves in deep water are dispersive in nature. The

phase velocity of the waves is

, whereas the

group velocity is

, whereas the

group velocity is

. In other

words, the group velocity is half the phase velocity, and is largest for long wavelength

(i.e., small

. In other

words, the group velocity is half the phase velocity, and is largest for long wavelength

(i.e., small  ) waves.

) waves.

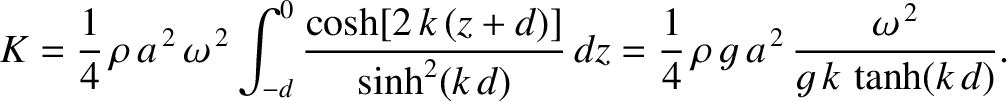

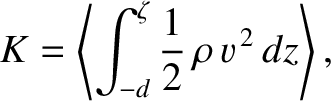

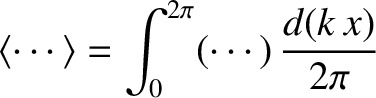

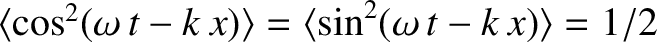

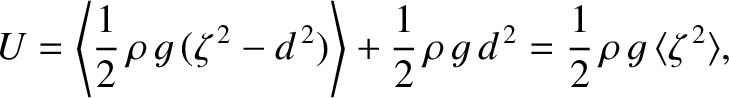

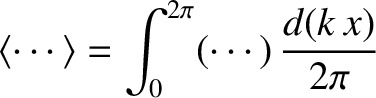

The mean kinetic energy per unit surface area associated with a gravity wave is defined

|

(9.290) |

where

|

(9.291) |

is the vertical displacement at the surface, and

|

(9.292) |

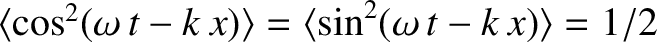

represents an average over a wavelength. Given that

, it follows from Equations (9.286) and (9.287) that, to second order in

, it follows from Equations (9.286) and (9.287) that, to second order in  ,

,

|

(9.293) |

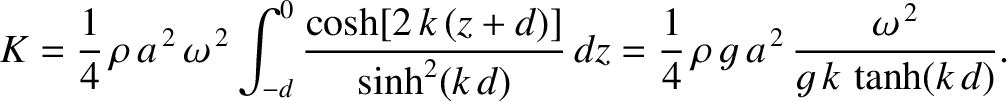

Making use of the general dispersion relation (9.283), we obtain

|

(9.294) |

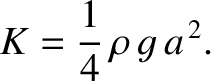

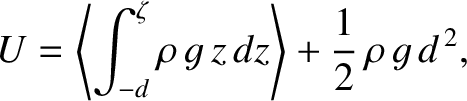

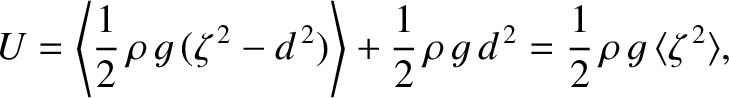

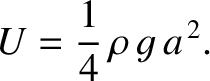

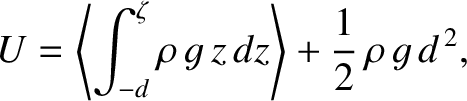

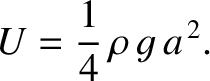

The mean potential energy perturbation per unit surface area associated with a gravity wave is defined

|

(9.295) |

which yields

|

(9.296) |

or

|

(9.297) |

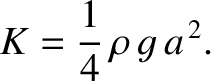

In other words, the mean potential energy per unit surface area of a gravity wave is equal to its mean kinetic

energy per unit surface area.

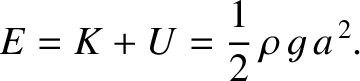

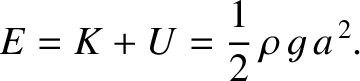

Finally, the mean total energy per unit surface area associated with a gravity wave is

|

(9.298) |

This energy depends on the wave amplitude at the surface, but is independent of the wavelength, or the water depth.

, located on the surface of the Earth. Let us

find the dispersion relation of a plane wave propagating across the water's surface. Suppose that the Cartesian coordinate

, located on the surface of the Earth. Let us

find the dispersion relation of a plane wave propagating across the water's surface. Suppose that the Cartesian coordinate  measures horizontal distance,

while the coordinate

measures horizontal distance,

while the coordinate  measures vertical height, with

measures vertical height, with  corresponding to the unperturbed surface of the water.

Let there be no variation in the

corresponding to the unperturbed surface of the water.

Let there be no variation in the  -direction. In other words, let the wavefronts of the wave all be parallel to the

-direction. In other words, let the wavefronts of the wave all be parallel to the  -axis. Finally, let

-axis. Finally, let

and

and

be the perturbed horizontal and

vertical velocity fields of the water due to the wave. It is assumed that there is no

motion in the

be the perturbed horizontal and

vertical velocity fields of the water due to the wave. It is assumed that there is no

motion in the  -direction.

-direction.

and

and  ,

,  and

and  , and

, and  and

and  . The element has two faces, of area

. The element has two faces, of area  , perpendicular to the

, perpendicular to the  -axis, located at

-axis, located at

and

and  . Water flows into the element through the former face

at the rate

. Water flows into the element through the former face

at the rate

(i.e., the product of the area of the face and the

normal velocity), and out of the element though the

latter face at the rate

(i.e., the product of the area of the face and the

normal velocity), and out of the element though the

latter face at the rate

. The element also has two

faces perpendicular to the

. The element also has two

faces perpendicular to the  -axis, but there is no flow through these faces, because

-axis, but there is no flow through these faces, because

. Finally, the element has two faces, of area

. Finally, the element has two faces, of area  , perpendicular to the

, perpendicular to the  -axis, located at

-axis, located at

and

and  . Water flows into the element through the former face

at the rate

. Water flows into the element through the former face

at the rate

, and out of the element though the

latter face at the rate

, and out of the element though the

latter face at the rate

.

Thus, the net rate at which water flows into the element is

.

Thus, the net rate at which water flows into the element is

.

Likewise, the net rate at which water flows out of the element is

.

Likewise, the net rate at which water flows out of the element is

. If the water is to remain incompressible

then the inflow and outflow rates must match. In other words,

. If the water is to remain incompressible

then the inflow and outflow rates must match. In other words,

![$\displaystyle \left[\frac{v_x(x+dx,z,t)-v_x(x,z,t)}{dx} + \frac{v_z(x,z+dz,t)-v_z(x,z,t)}{dz} \right]dx\,dy\,dz=0.$](img3003.png)

.9.1 Incidentally,

it is reasonable to neglect the finite compressibility of water in this investigation because sound waves (which require finite compressibility)

propagate much faster than surface waves, and, therefore, do not couple to them. (See the two footnotes in this section.)

.9.1 Incidentally,

it is reasonable to neglect the finite compressibility of water in this investigation because sound waves (which require finite compressibility)

propagate much faster than surface waves, and, therefore, do not couple to them. (See the two footnotes in this section.)

and

and  ,

,  and

and  , and

, and  and

and  . The mass of this element is

. The mass of this element is

, where

, where

is the uniform mass density of water. Suppose

that

is the uniform mass density of water. Suppose

that  is the pressure in the water, which is assumed to be isotropic (Batchelor 2000).

The net horizontal force on the element is

is the pressure in the water, which is assumed to be isotropic (Batchelor 2000).

The net horizontal force on the element is

(because force is pressure times area, and the external pressure forces

acting on the element are directed inward normal to its surface). Hence, the element's horizontal equation of motion is

(because force is pressure times area, and the external pressure forces

acting on the element are directed inward normal to its surface). Hence, the element's horizontal equation of motion is

![$\displaystyle \rho\,dx\,dy\,dz\,\frac{\partial v_x(x,z,t)}{\partial t} = -\left[\frac{p(x+dx,z,t)-p(x,z,t)}{dx}\right]dx\,dy\,dz,$](img3013.png)

, due to gravity. Hence, we obtain

[See Equation (7.193).]

, due to gravity. Hence, we obtain

[See Equation (7.193).]

is atmospheric pressure (i.e., the air pressure just above the surface of the water), and

is atmospheric pressure (i.e., the air pressure just above the surface of the water), and  is the pressure perturbation due to the wave. In the absence of

the wave, the water pressure at a depth

is the pressure perturbation due to the wave. In the absence of

the wave, the water pressure at a depth  below the surface is

below the surface is

(Batchelor 2000).

Substitution into Equations (9.262) and (9.263) yields

It follows that

(Batchelor 2000).

Substitution into Equations (9.262) and (9.263) yields

It follows that

. Assuming that the water always remains in contact

with this surface, the appropriate physical constraint at the lower boundary is

. Assuming that the water always remains in contact

with this surface, the appropriate physical constraint at the lower boundary is

(i.e., there is no vertical motion of the water at the lower boundary), or

(i.e., there is no vertical motion of the water at the lower boundary), or

represent the vertical displacement of the water's surface. It

follows that

The physical constraint at the surface is that the water pressure is equal to atmospheric pressure, because there cannot be a pressure discontinuity across a free surface (in the absence of surface tension).

Thus, it follows from Equation (9.264) that

Finally, differentiating with respect to

represent the vertical displacement of the water's surface. It

follows that

The physical constraint at the surface is that the water pressure is equal to atmospheric pressure, because there cannot be a pressure discontinuity across a free surface (in the absence of surface tension).

Thus, it follows from Equation (9.264) that

Finally, differentiating with respect to  , and making use of Equations (9.273) and (9.275), we obtain

Hence, the problem boils down to solving Laplace's equation, (9.272), subject

to the physical constraints (9.274) and (9.277).

, and making use of Equations (9.273) and (9.275), we obtain

Hence, the problem boils down to solving Laplace's equation, (9.272), subject

to the physical constraints (9.274) and (9.277).

and

and

.

Hence, the most general wave-like solution to Laplace's equation is

.

Hence, the most general wave-like solution to Laplace's equation is

and

and  are arbitrary constants. The boundary condition (9.274)

is satisfied provided that

are arbitrary constants. The boundary condition (9.274)

is satisfied provided that

, giving

The boundary condition (9.277) yields

, giving

The boundary condition (9.277) yields

, propagating horizontally through water of depth

, propagating horizontally through water of depth  , has a phase velocity

Moreover, the ratio of the group to the phase velocity is

Finally, the

velocity fields associated with a gravity wave of surface amplitude

, has a phase velocity

Moreover, the ratio of the group to the phase velocity is

Finally, the

velocity fields associated with a gravity wave of surface amplitude  are

are

), Equation (9.283) reduces to

the linear dispersion relation

), Equation (9.283) reduces to

the linear dispersion relation

for

for  . (See Appendix B.)

It follows that gravity waves in shallow water are non-dispersive in nature, and

propagate at the phase velocity

. (See Appendix B.)

It follows that gravity waves in shallow water are non-dispersive in nature, and

propagate at the phase velocity

. On the other hand, in deep water (i.e.,

. On the other hand, in deep water (i.e.,  ), Equation (9.283) reduces to

the nonlinear dispersion relation

), Equation (9.283) reduces to

the nonlinear dispersion relation

for

for  .

We conclude that gravity waves in deep water are dispersive in nature. The

phase velocity of the waves is

.

We conclude that gravity waves in deep water are dispersive in nature. The

phase velocity of the waves is

, whereas the

group velocity is

, whereas the

group velocity is

. In other

words, the group velocity is half the phase velocity, and is largest for long wavelength

(i.e., small

. In other

words, the group velocity is half the phase velocity, and is largest for long wavelength

(i.e., small  ) waves.

) waves.

, it follows from Equations (9.286) and (9.287) that, to second order in

, it follows from Equations (9.286) and (9.287) that, to second order in  ,

,