Normal Reflection and Transmission at Interfaces

Consider two uniform semi-infinite strings that run along the  -axis, and are tied together at

-axis, and are tied together at

. Let the first string be of density per unit length

. Let the first string be of density per unit length  , and occupy the

region

, and occupy the

region  , and let the second string be of density per unit length

, and let the second string be of density per unit length  , and

occupy the region

, and

occupy the region  . The tensions in the two strings must

be equal, otherwise the string interface would not be in force balance

in the

. The tensions in the two strings must

be equal, otherwise the string interface would not be in force balance

in the  -direction. Let

-direction. Let  be the common tension. Suppose that a transverse wave of angular frequency

be the common tension. Suppose that a transverse wave of angular frequency  is launched

from a wave source at

is launched

from a wave source at  , and propagates towards the interface. Assuming that

, and propagates towards the interface. Assuming that

, we would expect the

wave incident on the interface to be partially reflected, and partially transmitted. The

frequencies of the incident, reflected, and transmitted waves are all the same, because this

property of the waves is ultimately determined by the oscillation frequency of the wave source.

Hence, in the region

, we would expect the

wave incident on the interface to be partially reflected, and partially transmitted. The

frequencies of the incident, reflected, and transmitted waves are all the same, because this

property of the waves is ultimately determined by the oscillation frequency of the wave source.

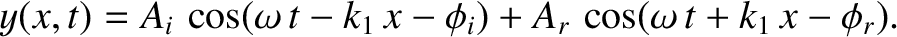

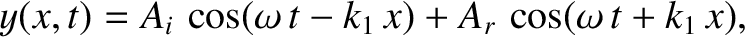

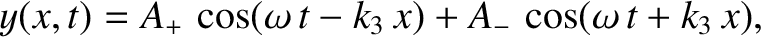

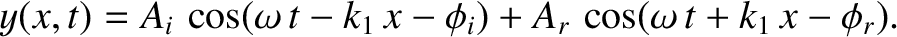

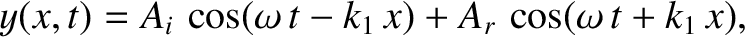

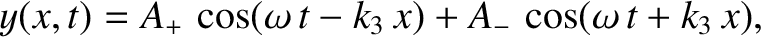

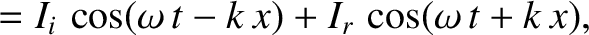

Hence, in the region  , the wave displacement takes the form

, the wave displacement takes the form

|

(6.79) |

In other words, the displacement is a linear superposition

of an incident wave and a reflected wave. The incident wave propagates in the positive  -direction, and is of

amplitude

-direction, and is of

amplitude  , wavenumber

, wavenumber

, and

phase angle

, and

phase angle  . The reflected wave propagates in the negative

. The reflected wave propagates in the negative  -direction, and is of

amplitude

-direction, and is of

amplitude  , wavenumber

, wavenumber

, and

phase angle

, and

phase angle  .

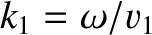

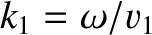

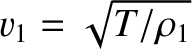

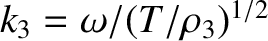

Here,

.

Here,

is the phase velocity of traveling

waves on the first string.

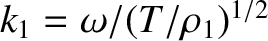

In the region

is the phase velocity of traveling

waves on the first string.

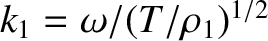

In the region  , the wave displacement takes the form

, the wave displacement takes the form

|

(6.80) |

In other words, the displacement is solely due to a transmitted wave

that propagates in the positive  -direction, and is of amplitude

-direction, and is of amplitude  ,

wavenumber

,

wavenumber

, and phase angle

, and phase angle  . Here,

. Here,

is the phase velocity of traveling waves on the second string. Incidentally, there is no backward traveling wave in the region

is the phase velocity of traveling waves on the second string. Incidentally, there is no backward traveling wave in the region

because such a wave could only originate from a source at

because such a wave could only originate from a source at  , and there is no such source in the problem

under consideration.

, and there is no such source in the problem

under consideration.

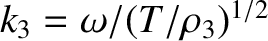

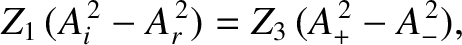

Let us consider the matching conditions at the interface between the two

strings; that is, at  . First, because the two strings are tied together at

. First, because the two strings are tied together at  , their

transverse displacements at this point must equal one another.

In other words,

, their

transverse displacements at this point must equal one another.

In other words,

|

(6.81) |

or

|

(6.82) |

The only way that the previous equation can be satisfied for all values of  is if

is if

. This being the case, the common

. This being the case, the common

factor

cancels out, and we are left with

factor

cancels out, and we are left with

|

(6.83) |

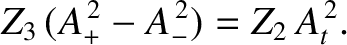

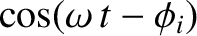

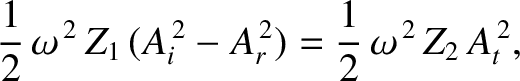

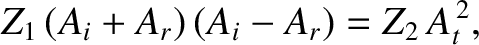

Second, because the two strings lack an energy dissipation

mechanism, the energy flux into the interface must match that out of the

interface. In other words,

|

(6.84) |

where

and

and

are the impedances of the

first and second strings, respectively. The previous expression

reduces to

are the impedances of the

first and second strings, respectively. The previous expression

reduces to

|

(6.85) |

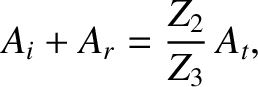

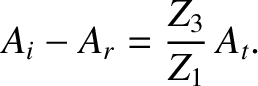

which, when combined with Equation (6.83), yields

|

(6.86) |

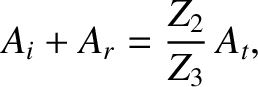

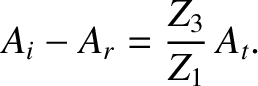

Equations (6.83) and (6.86) can be solved to give

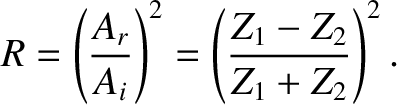

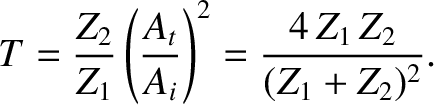

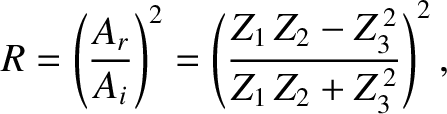

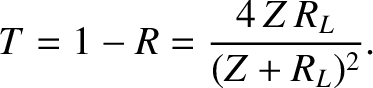

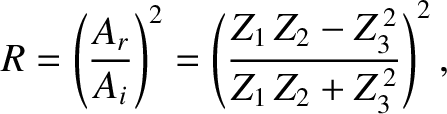

The coefficient of reflection,  , is defined as the ratio of the reflected to the incident

energy flux; that is,

, is defined as the ratio of the reflected to the incident

energy flux; that is,

|

(6.89) |

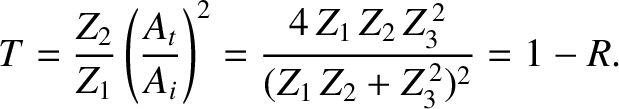

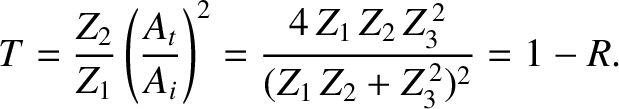

The coefficient of transmission,  , is defined as the ratio of the

transmitted to the incident energy flux; that is,

, is defined as the ratio of the

transmitted to the incident energy flux; that is,

|

(6.90) |

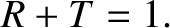

It can be seen that

|

(6.91) |

In other words, any incident wave energy that is not reflected is transmitted.

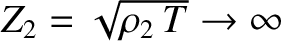

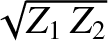

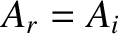

Suppose that the density per unit length of the second string,  , tends to infinity, so that

, tends to infinity, so that

. It follows from Equations (6.87) and

(6.88) that

. It follows from Equations (6.87) and

(6.88) that  and

and  . Likewise, Equations (6.89) and (6.90) yield

. Likewise, Equations (6.89) and (6.90) yield  and

and  . Hence, the interface between the

two strings is stationary (because it oscillates with amplitude

. Hence, the interface between the

two strings is stationary (because it oscillates with amplitude  ), and there is no transmitted energy. In

other words, the second string acts exactly like a fixed boundary. It follows that

when a transverse wave on a string is incident at a fixed boundary then it is

perfectly reflected with a phase shift of

), and there is no transmitted energy. In

other words, the second string acts exactly like a fixed boundary. It follows that

when a transverse wave on a string is incident at a fixed boundary then it is

perfectly reflected with a phase shift of  radians. In other words,

radians. In other words,  .

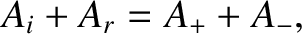

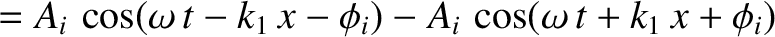

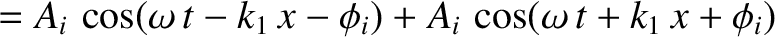

Thus, the resultant wave displacement on the string becomes

.

Thus, the resultant wave displacement on the string becomes

where use has been made of the trigonometric identity

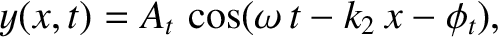

![$\cos a-\cos b \equiv 2\,\sin[(a+b)/2]\,\sin[(b-a)/2]$](img1556.png) . (See Appendix B.) We conclude that the incident and reflected waves interfere in such

a manner as to produce a standing wave with a node at the fixed boundary.

. (See Appendix B.) We conclude that the incident and reflected waves interfere in such

a manner as to produce a standing wave with a node at the fixed boundary.

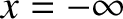

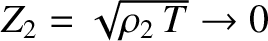

Suppose that the density per unit length of the second string,  , tends to zero, so that

, tends to zero, so that

. It follows from Equations (6.87) and

(6.88) that

. It follows from Equations (6.87) and

(6.88) that  and

and

. Likewise, Equations (6.89) and (6.90) yield

. Likewise, Equations (6.89) and (6.90) yield  and

and  . Hence, the interface between the

two strings oscillates at twice the amplitude of the incident wave (that is, the

interface is a point of maximal amplitude oscillation), and there is no transmitted energy. In

other words, the second string acts exactly like a free boundary. It follows that

when a transverse wave on a string is incident at a free boundary then it is

perfectly reflected with zero phase shift. In other words,

. Hence, the interface between the

two strings oscillates at twice the amplitude of the incident wave (that is, the

interface is a point of maximal amplitude oscillation), and there is no transmitted energy. In

other words, the second string acts exactly like a free boundary. It follows that

when a transverse wave on a string is incident at a free boundary then it is

perfectly reflected with zero phase shift. In other words,  .

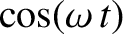

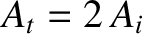

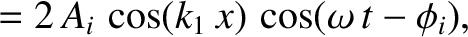

Thus, the resultant wave displacement on the string becomes

.

Thus, the resultant wave displacement on the string becomes

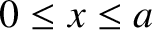

where use has been made of the trigonometric identity

![$\cos a + \cos b\equiv 2\,\cos[(a+b)/2]\,\cos[(a-b)/2]$](img723.png) . (See Appendix B.) We conclude that the incident and reflected waves interfere in such

a manner as to produce a standing wave with an anti-node at the free boundary.

. (See Appendix B.) We conclude that the incident and reflected waves interfere in such

a manner as to produce a standing wave with an anti-node at the free boundary.

Suppose that two strings of mass per unit length  and

and  are

separated by a short section of string of mass per unit length

are

separated by a short section of string of mass per unit length  . Let all

three strings have the common tension

. Let all

three strings have the common tension  . Suppose that the first and second strings occupy

the regions

. Suppose that the first and second strings occupy

the regions  and

and  , respectively. Thus, the middle string occupies the

region

, respectively. Thus, the middle string occupies the

region

. Moreover, the interface between the first and middle

strings is at

. Moreover, the interface between the first and middle

strings is at  , and the interface between the middle and

second strings is at

, and the interface between the middle and

second strings is at  . Suppose that a wave of angular frequency

. Suppose that a wave of angular frequency  is launched

from a wave source at

is launched

from a wave source at  , and propagates towards the two interfaces. We

would expect this wave to be partially reflected and partially transmitted at the first

interface (

, and propagates towards the two interfaces. We

would expect this wave to be partially reflected and partially transmitted at the first

interface ( ), and the resulting transmitted wave to then be partially

reflected and partially transmitted at the second interface (

), and the resulting transmitted wave to then be partially

reflected and partially transmitted at the second interface ( ). Thus, we can write the

wave displacement in the region

). Thus, we can write the

wave displacement in the region  as

as

|

(6.94) |

where  is the amplitude of the incident wave,

is the amplitude of the incident wave,  is the amplitude

of the reflected wave, and

is the amplitude

of the reflected wave, and

.

Here, the phase angles of the two waves have been chosen so as to

facilitate the matching process at

.

Here, the phase angles of the two waves have been chosen so as to

facilitate the matching process at  .

The wave displacement in the region

.

The wave displacement in the region  takes the form

takes the form

|

(6.95) |

where  is the amplitude of the final transmitted wave, and

is the amplitude of the final transmitted wave, and

. Finally, the wave displacement in the region

. Finally, the wave displacement in the region

is written

is written

|

(6.96) |

where  and

and  are the amplitudes of the forward- and backward-propagating waves on the

middle string, respectively, and

are the amplitudes of the forward- and backward-propagating waves on the

middle string, respectively, and

. Continuity of the

transverse displacement at

. Continuity of the

transverse displacement at  yields

yields

|

(6.97) |

where a common factor

has cancelled out.

Continuity of the energy flux at

has cancelled out.

Continuity of the energy flux at  gives

gives

|

(6.98) |

so the previous two expressions can be combined to produce

|

(6.99) |

Continuity of the transverse displacement at  yields

yields

|

(6.100) |

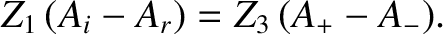

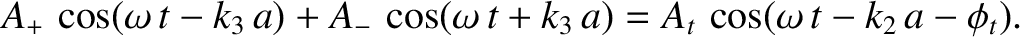

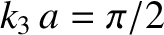

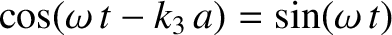

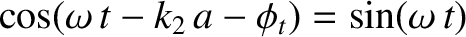

Suppose that the length of the middle string is one quarter of a wavelength; that is,

. Furthermore, let

. Furthermore, let

. It follows that

. It follows that

,

,

, and

, and

. Thus, canceling out a

common factor

. Thus, canceling out a

common factor

, the previous expression yields

, the previous expression yields

|

(6.101) |

Continuity of the energy flux at  gives

gives

|

(6.102) |

so the previous two equations can be combined to generate

|

(6.103) |

Equations (6.97) and (6.103) yield

|

(6.104) |

whereas Equations (6.99) and (6.101) give

|

(6.105) |

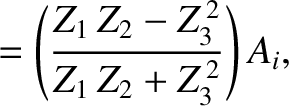

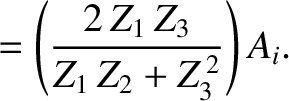

Hence, combining the previous two expression, we obtain

Finally, the overall coefficient of reflection is

|

(6.108) |

whereas the overall coefficient of transmission becomes

|

(6.109) |

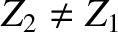

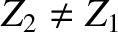

Suppose that the impedance of the middle string is the geometric mean of

the impedances of the two outer strings; that is,

.

In this case, it follows, from the previous two equations, that

.

In this case, it follows, from the previous two equations, that  and

and  . In

other words, there is no reflection of the incident wave, and all of the

incident energy ends up being transmitted across the middle string from the leftmost to the

rightmost string. Thus, if we want to transmit transverse wave energy from a string

of impedance

. In

other words, there is no reflection of the incident wave, and all of the

incident energy ends up being transmitted across the middle string from the leftmost to the

rightmost string. Thus, if we want to transmit transverse wave energy from a string

of impedance  to a string of impedance

to a string of impedance  (where

(where

) in the most efficient manner

possible—that is, with no reflection of the incident energy flux—then we can

achieve this by connecting the two strings via a short section of string whose length is

one quarter of a wavelength, and whose impedance is

) in the most efficient manner

possible—that is, with no reflection of the incident energy flux—then we can

achieve this by connecting the two strings via a short section of string whose length is

one quarter of a wavelength, and whose impedance is

.

This procedure is known as impedance matching.

Incidentally, impedance matching works because the one quarter of a wavelength (in length) middle string introduces a phase

difference of

.

This procedure is known as impedance matching.

Incidentally, impedance matching works because the one quarter of a wavelength (in length) middle string introduces a phase

difference of  radians (i.e., the phase increase of a wave that travels from

radians (i.e., the phase increase of a wave that travels from  to

to  , and back again)

between the backward traveling wave reflected from the first interface (at

, and back again)

between the backward traveling wave reflected from the first interface (at  ) and the backward traveling

wave reflected from the second interface (at

) and the backward traveling

wave reflected from the second interface (at  ). Furthermore, if

). Furthermore, if

then the two

backward traveling waves have the same amplitude in the region

then the two

backward traveling waves have the same amplitude in the region  . It follows that the two waves undergo total destructive

interference in this region, which implies that there is no reflected wave on the first string.

. It follows that the two waves undergo total destructive

interference in this region, which implies that there is no reflected wave on the first string.

The previous analysis of the reflection and transmission of

transverse waves at an interface between two strings is also applicable to the reflection

and transmission of other types of wave incident on an interface between two media of

differing impedances. For example, consider a transmission line, such

as a co-axial cable. Suppose that the line occupies the region  , and is

terminated (at

, and is

terminated (at  ) by a load resistor of resistance

) by a load resistor of resistance  . Such a resistor might represent a

radio antenna [which acts just like a resistor in an electrical circuit, except that

the dissipated energy is radiated, rather than being converted into heat energy (Fitzpatrick 2088)].

Suppose that a signal of angular frequency

. Such a resistor might represent a

radio antenna [which acts just like a resistor in an electrical circuit, except that

the dissipated energy is radiated, rather than being converted into heat energy (Fitzpatrick 2088)].

Suppose that a signal of angular frequency  is sent down the line

from a wave source at

is sent down the line

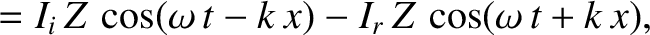

from a wave source at  . The current and voltage on the line

can be written

. The current and voltage on the line

can be written

where  is the amplitude of the incident signal,

is the amplitude of the incident signal,  the amplitude

of the signal reflected by the load,

the amplitude

of the signal reflected by the load,  the characteristic impedance of the line, and

the characteristic impedance of the line, and

.

Here,

.

Here,  is the characteristic phase velocity at which signals propagate down the line.

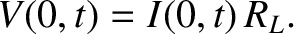

(See Section 6.6.) The resistor obeys Ohm's law,

which yields

is the characteristic phase velocity at which signals propagate down the line.

(See Section 6.6.) The resistor obeys Ohm's law,

which yields

|

(6.112) |

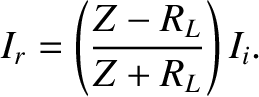

It follows, from the previous three equations, that

|

(6.113) |

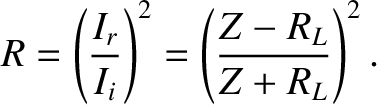

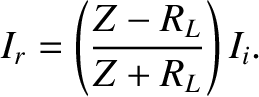

Hence, the coefficient of reflection, which is the ratio of the power reflected by the load to the power sent down the line, is

|

(6.114) |

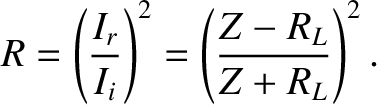

Furthermore, the coefficient of transmission, which is the ratio

of the power absorbed by the load to the power sent down the line,

takes the form

|

(6.115) |

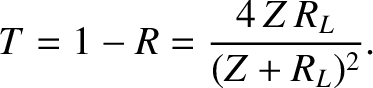

It can be seen, by comparison with Equations (6.89) and (6.90),

that the load terminating the line acts just like another transmission line of impedance  . It follows that power can only be efficiently sent down a transmission line, and transferred to a terminating load, when the impedance of the line matches the effective impedance

of the load (which, in this case, is the same as the resistance of the load). In other words,

when

. It follows that power can only be efficiently sent down a transmission line, and transferred to a terminating load, when the impedance of the line matches the effective impedance

of the load (which, in this case, is the same as the resistance of the load). In other words,

when  there is no reflection of the signal sent down the line (i.e.,

there is no reflection of the signal sent down the line (i.e.,  ),

and all of the signal energy is therefore absorbed by the load (i.e.,

),

and all of the signal energy is therefore absorbed by the load (i.e.,  ). As an example, a

half-wave antenna (i.e., an antenna whose length is half the wavelength

of the emitted radiation) has a characteristic impedance of

). As an example, a

half-wave antenna (i.e., an antenna whose length is half the wavelength

of the emitted radiation) has a characteristic impedance of

(Held and Marion 1995). Hence, a

transmission line used to feed energy into such an antenna should also have

a characteristic impedance of

(Held and Marion 1995). Hence, a

transmission line used to feed energy into such an antenna should also have

a characteristic impedance of

. Suppose, however, that we encounter a situation in which the

impedance of a transmission line,

. Suppose, however, that we encounter a situation in which the

impedance of a transmission line,  , does not match that of its

terminating load,

, does not match that of its

terminating load,  . Can anything be done to avoid reflection of the signal sent down the line? It turns out,

by analogy with the previous analysis, that if the line is connected

to the load via a short section of transmission line whose length is one quarter

of the wavelength of the signal, and whose characteristic impedance is

. Can anything be done to avoid reflection of the signal sent down the line? It turns out,

by analogy with the previous analysis, that if the line is connected

to the load via a short section of transmission line whose length is one quarter

of the wavelength of the signal, and whose characteristic impedance is

, then there is no reflection of the signal; that is, all of the signal power is absorbed by the

load. A short section of transmission line used in this manner is known as a

quarter-wave transformer.

, then there is no reflection of the signal; that is, all of the signal power is absorbed by the

load. A short section of transmission line used in this manner is known as a

quarter-wave transformer.

-axis, and are tied together at

-axis, and are tied together at

. Let the first string be of density per unit length

. Let the first string be of density per unit length  , and occupy the

region

, and occupy the

region  , and let the second string be of density per unit length

, and let the second string be of density per unit length  , and

occupy the region

, and

occupy the region  . The tensions in the two strings must

be equal, otherwise the string interface would not be in force balance

in the

. The tensions in the two strings must

be equal, otherwise the string interface would not be in force balance

in the  -direction. Let

-direction. Let  be the common tension. Suppose that a transverse wave of angular frequency

be the common tension. Suppose that a transverse wave of angular frequency  is launched

from a wave source at

is launched

from a wave source at  , and propagates towards the interface. Assuming that

, and propagates towards the interface. Assuming that

, we would expect the

wave incident on the interface to be partially reflected, and partially transmitted. The

frequencies of the incident, reflected, and transmitted waves are all the same, because this

property of the waves is ultimately determined by the oscillation frequency of the wave source.

Hence, in the region

, we would expect the

wave incident on the interface to be partially reflected, and partially transmitted. The

frequencies of the incident, reflected, and transmitted waves are all the same, because this

property of the waves is ultimately determined by the oscillation frequency of the wave source.

Hence, in the region  , the wave displacement takes the form

, the wave displacement takes the form

-direction, and is of

amplitude

-direction, and is of

amplitude  , wavenumber

, wavenumber

, and

phase angle

, and

phase angle  . The reflected wave propagates in the negative

. The reflected wave propagates in the negative  -direction, and is of

amplitude

-direction, and is of

amplitude  , wavenumber

, wavenumber

, and

phase angle

, and

phase angle  .

Here,

.

Here,

is the phase velocity of traveling

waves on the first string.

In the region

is the phase velocity of traveling

waves on the first string.

In the region  , the wave displacement takes the form

, the wave displacement takes the form

-direction, and is of amplitude

-direction, and is of amplitude  ,

wavenumber

,

wavenumber

, and phase angle

, and phase angle  . Here,

. Here,

is the phase velocity of traveling waves on the second string. Incidentally, there is no backward traveling wave in the region

is the phase velocity of traveling waves on the second string. Incidentally, there is no backward traveling wave in the region

because such a wave could only originate from a source at

because such a wave could only originate from a source at  , and there is no such source in the problem

under consideration.

, and there is no such source in the problem

under consideration.

. First, because the two strings are tied together at

. First, because the two strings are tied together at  , their

transverse displacements at this point must equal one another.

In other words,

, their

transverse displacements at this point must equal one another.

In other words,

is if

is if

. This being the case, the common

. This being the case, the common

factor

cancels out, and we are left with

Second, because the two strings lack an energy dissipation

mechanism, the energy flux into the interface must match that out of the

interface. In other words,

factor

cancels out, and we are left with

Second, because the two strings lack an energy dissipation

mechanism, the energy flux into the interface must match that out of the

interface. In other words,

and

and

are the impedances of the

first and second strings, respectively. The previous expression

reduces to

are the impedances of the

first and second strings, respectively. The previous expression

reduces to

, is defined as the ratio of the reflected to the incident

energy flux; that is,

The coefficient of transmission,

, is defined as the ratio of the reflected to the incident

energy flux; that is,

The coefficient of transmission,  , is defined as the ratio of the

transmitted to the incident energy flux; that is,

It can be seen that

, is defined as the ratio of the

transmitted to the incident energy flux; that is,

It can be seen that

, tends to infinity, so that

, tends to infinity, so that

. It follows from Equations (6.87) and

(6.88) that

. It follows from Equations (6.87) and

(6.88) that  and

and  . Likewise, Equations (6.89) and (6.90) yield

. Likewise, Equations (6.89) and (6.90) yield  and

and  . Hence, the interface between the

two strings is stationary (because it oscillates with amplitude

. Hence, the interface between the

two strings is stationary (because it oscillates with amplitude  ), and there is no transmitted energy. In

other words, the second string acts exactly like a fixed boundary. It follows that

when a transverse wave on a string is incident at a fixed boundary then it is

perfectly reflected with a phase shift of

), and there is no transmitted energy. In

other words, the second string acts exactly like a fixed boundary. It follows that

when a transverse wave on a string is incident at a fixed boundary then it is

perfectly reflected with a phase shift of  radians. In other words,

radians. In other words,  .

Thus, the resultant wave displacement on the string becomes

.

Thus, the resultant wave displacement on the string becomes

![$\cos a-\cos b \equiv 2\,\sin[(a+b)/2]\,\sin[(b-a)/2]$](img1556.png) . (See Appendix B.) We conclude that the incident and reflected waves interfere in such

a manner as to produce a standing wave with a node at the fixed boundary.

. (See Appendix B.) We conclude that the incident and reflected waves interfere in such

a manner as to produce a standing wave with a node at the fixed boundary.

, tends to zero, so that

, tends to zero, so that

. It follows from Equations (6.87) and

(6.88) that

. It follows from Equations (6.87) and

(6.88) that  and

and

. Likewise, Equations (6.89) and (6.90) yield

. Likewise, Equations (6.89) and (6.90) yield  and

and  . Hence, the interface between the

two strings oscillates at twice the amplitude of the incident wave (that is, the

interface is a point of maximal amplitude oscillation), and there is no transmitted energy. In

other words, the second string acts exactly like a free boundary. It follows that

when a transverse wave on a string is incident at a free boundary then it is

perfectly reflected with zero phase shift. In other words,

. Hence, the interface between the

two strings oscillates at twice the amplitude of the incident wave (that is, the

interface is a point of maximal amplitude oscillation), and there is no transmitted energy. In

other words, the second string acts exactly like a free boundary. It follows that

when a transverse wave on a string is incident at a free boundary then it is

perfectly reflected with zero phase shift. In other words,  .

Thus, the resultant wave displacement on the string becomes

.

Thus, the resultant wave displacement on the string becomes

![$\cos a + \cos b\equiv 2\,\cos[(a+b)/2]\,\cos[(a-b)/2]$](img723.png) . (See Appendix B.) We conclude that the incident and reflected waves interfere in such

a manner as to produce a standing wave with an anti-node at the free boundary.

. (See Appendix B.) We conclude that the incident and reflected waves interfere in such

a manner as to produce a standing wave with an anti-node at the free boundary.

and

and  are

separated by a short section of string of mass per unit length

are

separated by a short section of string of mass per unit length  . Let all

three strings have the common tension

. Let all

three strings have the common tension  . Suppose that the first and second strings occupy

the regions

. Suppose that the first and second strings occupy

the regions  and

and  , respectively. Thus, the middle string occupies the

region

, respectively. Thus, the middle string occupies the

region

. Moreover, the interface between the first and middle

strings is at

. Moreover, the interface between the first and middle

strings is at  , and the interface between the middle and

second strings is at

, and the interface between the middle and

second strings is at  . Suppose that a wave of angular frequency

. Suppose that a wave of angular frequency  is launched

from a wave source at

is launched

from a wave source at  , and propagates towards the two interfaces. We

would expect this wave to be partially reflected and partially transmitted at the first

interface (

, and propagates towards the two interfaces. We

would expect this wave to be partially reflected and partially transmitted at the first

interface ( ), and the resulting transmitted wave to then be partially

reflected and partially transmitted at the second interface (

), and the resulting transmitted wave to then be partially

reflected and partially transmitted at the second interface ( ). Thus, we can write the

wave displacement in the region

). Thus, we can write the

wave displacement in the region  as

as

is the amplitude of the incident wave,

is the amplitude of the incident wave,  is the amplitude

of the reflected wave, and

is the amplitude

of the reflected wave, and

.

Here, the phase angles of the two waves have been chosen so as to

facilitate the matching process at

.

Here, the phase angles of the two waves have been chosen so as to

facilitate the matching process at  .

The wave displacement in the region

.

The wave displacement in the region  takes the form

takes the form

is the amplitude of the final transmitted wave, and

is the amplitude of the final transmitted wave, and

. Finally, the wave displacement in the region

. Finally, the wave displacement in the region

is written

is written

and

and  are the amplitudes of the forward- and backward-propagating waves on the

middle string, respectively, and

are the amplitudes of the forward- and backward-propagating waves on the

middle string, respectively, and

. Continuity of the

transverse displacement at

. Continuity of the

transverse displacement at  yields

where a common factor

yields

where a common factor

has cancelled out.

Continuity of the energy flux at

has cancelled out.

Continuity of the energy flux at  gives

gives

yields

yields

. Furthermore, let

. Furthermore, let

. It follows that

. It follows that

,

,

, and

, and

. Thus, canceling out a

common factor

. Thus, canceling out a

common factor

, the previous expression yields

Continuity of the energy flux at

, the previous expression yields

Continuity of the energy flux at  gives

gives

.

In this case, it follows, from the previous two equations, that

.

In this case, it follows, from the previous two equations, that  and

and  . In

other words, there is no reflection of the incident wave, and all of the

incident energy ends up being transmitted across the middle string from the leftmost to the

rightmost string. Thus, if we want to transmit transverse wave energy from a string

of impedance

. In

other words, there is no reflection of the incident wave, and all of the

incident energy ends up being transmitted across the middle string from the leftmost to the

rightmost string. Thus, if we want to transmit transverse wave energy from a string

of impedance  to a string of impedance

to a string of impedance  (where

(where

) in the most efficient manner

possible—that is, with no reflection of the incident energy flux—then we can

achieve this by connecting the two strings via a short section of string whose length is

one quarter of a wavelength, and whose impedance is

) in the most efficient manner

possible—that is, with no reflection of the incident energy flux—then we can

achieve this by connecting the two strings via a short section of string whose length is

one quarter of a wavelength, and whose impedance is

.

This procedure is known as impedance matching.

Incidentally, impedance matching works because the one quarter of a wavelength (in length) middle string introduces a phase

difference of

.

This procedure is known as impedance matching.

Incidentally, impedance matching works because the one quarter of a wavelength (in length) middle string introduces a phase

difference of  radians (i.e., the phase increase of a wave that travels from

radians (i.e., the phase increase of a wave that travels from  to

to  , and back again)

between the backward traveling wave reflected from the first interface (at

, and back again)

between the backward traveling wave reflected from the first interface (at  ) and the backward traveling

wave reflected from the second interface (at

) and the backward traveling

wave reflected from the second interface (at  ). Furthermore, if

). Furthermore, if

then the two

backward traveling waves have the same amplitude in the region

then the two

backward traveling waves have the same amplitude in the region  . It follows that the two waves undergo total destructive

interference in this region, which implies that there is no reflected wave on the first string.

. It follows that the two waves undergo total destructive

interference in this region, which implies that there is no reflected wave on the first string.

, and is

terminated (at

, and is

terminated (at  ) by a load resistor of resistance

) by a load resistor of resistance  . Such a resistor might represent a

radio antenna [which acts just like a resistor in an electrical circuit, except that

the dissipated energy is radiated, rather than being converted into heat energy (Fitzpatrick 2088)].

Suppose that a signal of angular frequency

. Such a resistor might represent a

radio antenna [which acts just like a resistor in an electrical circuit, except that

the dissipated energy is radiated, rather than being converted into heat energy (Fitzpatrick 2088)].

Suppose that a signal of angular frequency  is sent down the line

from a wave source at

is sent down the line

from a wave source at  . The current and voltage on the line

can be written

. The current and voltage on the line

can be written

is the amplitude of the incident signal,

is the amplitude of the incident signal,  the amplitude

of the signal reflected by the load,

the amplitude

of the signal reflected by the load,  the characteristic impedance of the line, and

the characteristic impedance of the line, and

.

Here,

.

Here,  is the characteristic phase velocity at which signals propagate down the line.

(See Section 6.6.) The resistor obeys Ohm's law,

which yields

is the characteristic phase velocity at which signals propagate down the line.

(See Section 6.6.) The resistor obeys Ohm's law,

which yields

. It follows that power can only be efficiently sent down a transmission line, and transferred to a terminating load, when the impedance of the line matches the effective impedance

of the load (which, in this case, is the same as the resistance of the load). In other words,

when

. It follows that power can only be efficiently sent down a transmission line, and transferred to a terminating load, when the impedance of the line matches the effective impedance

of the load (which, in this case, is the same as the resistance of the load). In other words,

when  there is no reflection of the signal sent down the line (i.e.,

there is no reflection of the signal sent down the line (i.e.,  ),

and all of the signal energy is therefore absorbed by the load (i.e.,

),

and all of the signal energy is therefore absorbed by the load (i.e.,  ). As an example, a

half-wave antenna (i.e., an antenna whose length is half the wavelength

of the emitted radiation) has a characteristic impedance of

). As an example, a

half-wave antenna (i.e., an antenna whose length is half the wavelength

of the emitted radiation) has a characteristic impedance of

(Held and Marion 1995). Hence, a

transmission line used to feed energy into such an antenna should also have

a characteristic impedance of

(Held and Marion 1995). Hence, a

transmission line used to feed energy into such an antenna should also have

a characteristic impedance of

. Suppose, however, that we encounter a situation in which the

impedance of a transmission line,

. Suppose, however, that we encounter a situation in which the

impedance of a transmission line,  , does not match that of its

terminating load,

, does not match that of its

terminating load,  . Can anything be done to avoid reflection of the signal sent down the line? It turns out,

by analogy with the previous analysis, that if the line is connected

to the load via a short section of transmission line whose length is one quarter

of the wavelength of the signal, and whose characteristic impedance is

. Can anything be done to avoid reflection of the signal sent down the line? It turns out,

by analogy with the previous analysis, that if the line is connected

to the load via a short section of transmission line whose length is one quarter

of the wavelength of the signal, and whose characteristic impedance is

, then there is no reflection of the signal; that is, all of the signal power is absorbed by the

load. A short section of transmission line used in this manner is known as a

quarter-wave transformer.

, then there is no reflection of the signal; that is, all of the signal power is absorbed by the

load. A short section of transmission line used in this manner is known as a

quarter-wave transformer.