Next: Electron Diffraction Up: Wave Mechanics Previous: Introduction Contents

In 1905, Albert Einstein proposed a radical new theory of light in order to

account for the photoelectric effect. According to this theory, light

of fixed angular frequency  consists of a collection of indivisible discrete packages, called

quanta,11.1 whose energy is

consists of a collection of indivisible discrete packages, called

quanta,11.1 whose energy is

is a new constant of nature,

known as Planck's constant. (Strictly speaking, it is Planck's constant divided by

is a new constant of nature,

known as Planck's constant. (Strictly speaking, it is Planck's constant divided by  .) Incidentally,

.) Incidentally,  is called Planck's constant, rather than Einstein's constant, because Max Planck first introduced the concept of the quantization of light, in 1900, when trying

to account for the electromagnetic spectrum of a black body (i.e.,

a perfect emitter and absorber of electromagnetic radiation) (Gasiorowicz 1996).

is called Planck's constant, rather than Einstein's constant, because Max Planck first introduced the concept of the quantization of light, in 1900, when trying

to account for the electromagnetic spectrum of a black body (i.e.,

a perfect emitter and absorber of electromagnetic radiation) (Gasiorowicz 1996).

![\includegraphics[width=0.5\textwidth]{Chapter11/fig11_01.eps}](img3788.png) |

Suppose that the electrons at the surface of a piece of metal lie in a potential well

of depth  . In other words, the electrons have to acquire an energy

. In other words, the electrons have to acquire an energy  in order to be emitted from the surface. Here,

in order to be emitted from the surface. Here,  is generally called

the workfunction of the surface, and is a property of the

metal. Suppose that an electron absorbs a single quantum of light, otherwise known as a photon. Its energy

therefore increases by

is generally called

the workfunction of the surface, and is a property of the

metal. Suppose that an electron absorbs a single quantum of light, otherwise known as a photon. Its energy

therefore increases by

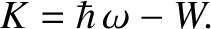

. If

. If

is greater than

is greater than  then the

electron is emitted from the surface with the residual kinetic energy

then the

electron is emitted from the surface with the residual kinetic energy

|

(11.2) |

,

and whose intercept with the

,

and whose intercept with the  axis is

axis is  . Finally, the number

of emitted electrons increases with the intensity of the light because, the

more intense the light, the larger the flux of photons onto the surface.

Thus, Einstein's quantum theory of light is capable of accounting for all

three of the previously mentioned observational facts regarding the photoelectric

effect. In the following, we shall assume that the central component of Einstein's theory—namely, Equation (11.1)—is a general result that applies to all particles, not

just photons.

. Finally, the number

of emitted electrons increases with the intensity of the light because, the

more intense the light, the larger the flux of photons onto the surface.

Thus, Einstein's quantum theory of light is capable of accounting for all

three of the previously mentioned observational facts regarding the photoelectric

effect. In the following, we shall assume that the central component of Einstein's theory—namely, Equation (11.1)—is a general result that applies to all particles, not

just photons.