Two-Dimensional Fourier Optics

Consider a monochromatic plane light wave, propagating in the  -direction, which is normally incident on an opaque

screen that occupies the plane

-direction, which is normally incident on an opaque

screen that occupies the plane  . Suppose that there is an irregularly shaped aperture cut in the screen, and

that the light that passes through this aperture travels to a flat projection screen occupying the plane

. Suppose that there is an irregularly shaped aperture cut in the screen, and

that the light that passes through this aperture travels to a flat projection screen occupying the plane  .

We wish to determine the interference/diffraction pattern that appears on the projection screen, as a function of the size

and shape of the aperture. We can achieve this goal by employing a modified

version of Huygen's principle. In Section 10.6, we

divided the aperture into infinitesimal parallel strips of equal height, and argued that each

strip emits a cylindrical wave in the forward direction that has the same amplitude and phase as the

light that illuminates it from behind. For the case of an irregularly shaped aperture, we can similarly divide the aperture into

infinitesimal squares of equal area, and argue that each square emits a spherical wave in the forward direction that has the

same amplitude and phase as the light that illuminates it from behind. [Recall that line sources and point sources emit

cylindrical and spherical waves, respectively. (See Sections 7.4 and 7.5.)]

Using analogous arguments to those employed in Section 10.2, we can show that

provided

.

We wish to determine the interference/diffraction pattern that appears on the projection screen, as a function of the size

and shape of the aperture. We can achieve this goal by employing a modified

version of Huygen's principle. In Section 10.6, we

divided the aperture into infinitesimal parallel strips of equal height, and argued that each

strip emits a cylindrical wave in the forward direction that has the same amplitude and phase as the

light that illuminates it from behind. For the case of an irregularly shaped aperture, we can similarly divide the aperture into

infinitesimal squares of equal area, and argue that each square emits a spherical wave in the forward direction that has the

same amplitude and phase as the light that illuminates it from behind. [Recall that line sources and point sources emit

cylindrical and spherical waves, respectively. (See Sections 7.4 and 7.5.)]

Using analogous arguments to those employed in Section 10.2, we can show that

provided

|

(10.70) |

where  is the characteristic size of the aperture, and

is the characteristic size of the aperture, and  is the wavelength of the light that illuminates it from behind, we are

in the far-field limit. In this limit, the interference/diffraction pattern appearing on the projection screen is entirely due to the phase

differences between the spherical waves that travel to a given point on the screen from different parts of the aperture. These

phase differences are produced by the slightly different distances traveled by these waves.

is the wavelength of the light that illuminates it from behind, we are

in the far-field limit. In this limit, the interference/diffraction pattern appearing on the projection screen is entirely due to the phase

differences between the spherical waves that travel to a given point on the screen from different parts of the aperture. These

phase differences are produced by the slightly different distances traveled by these waves.

Consider a spherical wave emitted from the point  ,

,  ,

,  in the aperture that travels to the point

in the aperture that travels to the point

,

,  ,

,  on the projection screen. The distance traveled by this wave is

on the projection screen. The distance traveled by this wave is

where

and

and

are the angular coordinates of the point on the projection screen. Here, we are assuming that

are the angular coordinates of the point on the projection screen. Here, we are assuming that

|

(10.72) |

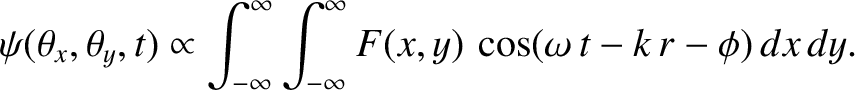

The wavefunction at the point  ,

,  on the projection screen is a linear superposition of the spherical waves that travel to it from all

parts of the aperture. It follows that

on the projection screen is a linear superposition of the spherical waves that travel to it from all

parts of the aperture. It follows that

|

(10.73) |

Here,  is an aperture function that takes the value

is an aperture function that takes the value  in the unblocked parts of the opaque screen, where

in the unblocked parts of the opaque screen, where  is the aperture area, and the

value zero in the blocked parts. We have neglected the

is the aperture area, and the

value zero in the blocked parts. We have neglected the  variation of the wave amplitudes (see Section 7.5)

because we are working in the far-field limit. It follows, from Equations (10.71) and (10.73), that

Here, we have made use of the fact that

variation of the wave amplitudes (see Section 7.5)

because we are working in the far-field limit. It follows, from Equations (10.71) and (10.73), that

Here, we have made use of the fact that

,

,

, and have also assumed that the aperture function is an even function of

both

, and have also assumed that the aperture function is an even function of

both  and

and  (i.e., the aperture is symmetric about

(i.e., the aperture is symmetric about  and

and  ). The intensity of the light at the point

). The intensity of the light at the point  ,

,  on the

projection screen is thus

on the

projection screen is thus

![$\displaystyle {\cal I}(\theta_x,\theta_y)\propto \langle \psi^{\,2}(\theta_x,\t...

...infty}^\infty F(x,y)\,\cos(k\,\theta_x\,x+k\,\theta_y\,y)\,dx\,dy\right]^{\,2}.$](img3509.png) |

(10.75) |

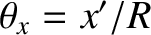

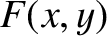

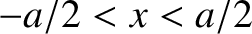

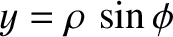

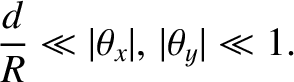

Figure:

Far-field interference/diffraction pattern produced by a rectangular aperture for which  . Dark regions indicate

high light intensity.

. Dark regions indicate

high light intensity.

|

|

Consider a rectangular aperture that occupies the region

and

and

in the

in the  -

- plane.

The intensity of the interference/diffraction pattern on the projection screen produced by such an aperture is

plane.

The intensity of the interference/diffraction pattern on the projection screen produced by such an aperture is

![$\displaystyle {\cal I}(\theta_x,\theta_y)\propto \left[\int_{-b/2}^{b/2}\int_{-...

...2}\cos(k\,\theta_x\,x+k\,\theta_y\,y)\,\frac{dx}{a}\,\frac{dy}{b}\right]^{\,2},$](img3514.png) |

(10.76) |

which yields

|

(10.77) |

This pattern is shown in Figure 10.13. It consists of a strong central maximum, that extends over the region

and

and

, surrounded by much weaker secondary maxima arranged on a rectangular grid. Incidentally, our assumption that

, surrounded by much weaker secondary maxima arranged on a rectangular grid. Incidentally, our assumption that

,

,

is only

self-consistent provided

is only

self-consistent provided

,

,  (i.e., provided the wavelength of the light is much less than the dimensions of

the aperture).

(i.e., provided the wavelength of the light is much less than the dimensions of

the aperture).

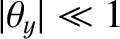

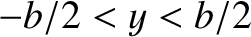

Figure:

The function

.

.

|

|

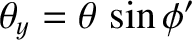

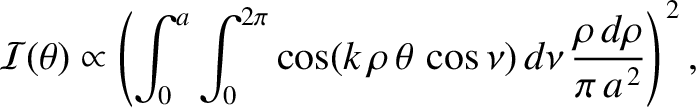

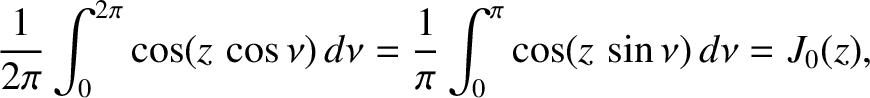

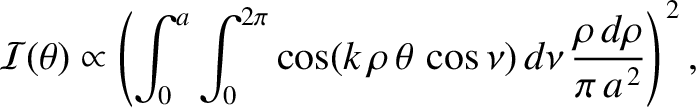

Consider a circular aperture that occupies the region

in the

in the  -

- plane. Let

plane. Let

,

,

,

,

, and

, and

. The

intensity of the interference/diffraction pattern on the projection screen produced by such an aperture is

. The

intensity of the interference/diffraction pattern on the projection screen produced by such an aperture is

![$\displaystyle {\cal I}(\theta,\phi') \propto\left(\int_0^a\int_0^{2\pi}\cos[k\,...

...theta\,\cos(\phi-\phi')]\,\frac{\rho\,d\phi\,d\rho}{\pi\,a^{\,2}}\right)^{\,2},$](img3526.png) |

(10.78) |

or

|

(10.79) |

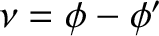

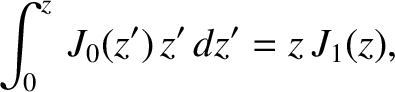

where

.

It is readily demonstrated that (Abramowitz and Stegun 1965)

.

It is readily demonstrated that (Abramowitz and Stegun 1965)

|

(10.80) |

where  is the Bessel function of degree zero introduced in Section 7.6.

It follows that

is the Bessel function of degree zero introduced in Section 7.6.

It follows that

![$\displaystyle {\cal I}(\theta) \propto \left[\frac{2}{\pi\,a^{\,2}}\int_0^a J_0...

...ft[\frac{2}{(k\,\theta\,a)^2}\int_0^{k\theta\,a}

J_0(z')\,z'\,dz'\right]^{\,2}.$](img3530.png) |

(10.81) |

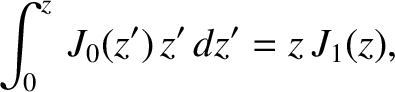

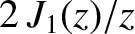

It can be shown that (Gradshteyn and Ryzhik 1980)

|

(10.82) |

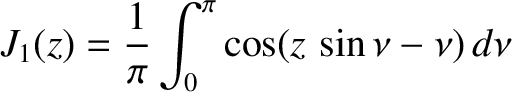

where (Abramowitz and Stegun 1965)

|

(10.83) |

is a Bessel function of degree one. Hence,

![$\displaystyle {\cal I}(\theta)\propto \left[\frac{2\,J_1(k\,a\,\theta)}{k\,a\,\theta}\right]^{\,2}.$](img3533.png) |

(10.84) |

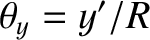

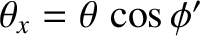

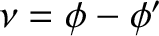

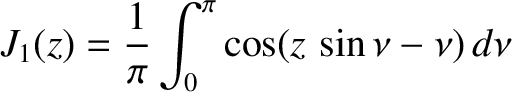

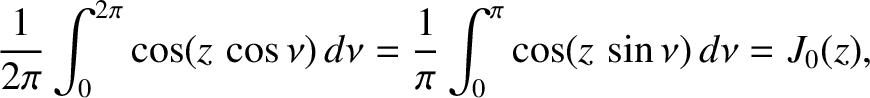

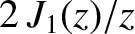

Figure 10.14 shows the function

, whereas Table 10.1 lists the first few values

of

, whereas Table 10.1 lists the first few values

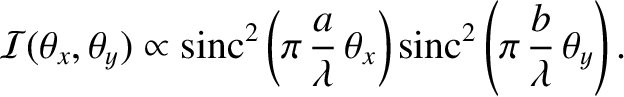

of  at which this function is zero. Finally, Figure 10.15 shows the interference/diffraction pattern

associated with a circular aperture. The pattern consists of a central disk, known as an Airy disk,

surrounded by much fainter concentric rings. The angular radius of the Airy disk is

at which this function is zero. Finally, Figure 10.15 shows the interference/diffraction pattern

associated with a circular aperture. The pattern consists of a central disk, known as an Airy disk,

surrounded by much fainter concentric rings. The angular radius of the Airy disk is

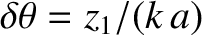

where

where

is the first zero of the function

is the first zero of the function

. It follows that

. It follows that

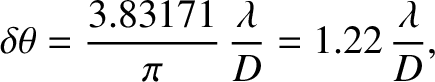

|

(10.85) |

where  is the diameter of the aperture.

is the diameter of the aperture.

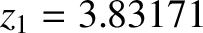

Table: 10.1

First few zeros of the function

. Source: Abramowitz and Stegun 1965.

. Source: Abramowitz and Stegun 1965.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| 1 |

3.83171 |

6 |

19.61586 |

| 2 |

7.01559 |

7 |

22.76008 |

| 3 |

10.17347 |

8 |

25.90367 |

| 4 |

13.32369 |

9 |

29.04683 |

| 5 |

16.47063 |

10 |

32.18968 |

|

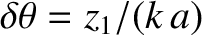

Figure 10.15:

Far-field interference/diffraction pattern produced by a circular aperture of radius  . Dark regions indicate high light intensity.

. Dark regions indicate high light intensity.

|

|

As we have already mentioned (see Section 10.7), when a point light source, such as a star, is observed in a telescope, what

is actually seen is the diffraction patten of the source produced by the objective aperture. If the aperture is

circular then then the telescope images the star as an Airy disk, surrounded by much fainter rings. Likewise, the

telescope images two neighboring stars as two Airy disks. The Rayleigh criterion (see Section 10.7) for resolving the two stars (i.e.,

for being able to tell that there are two stars, rather than one)

is that the angular distance,

, between the stars be greater than the angular radii of their Airy disks. This yields

, between the stars be greater than the angular radii of their Airy disks. This yields

|

(10.86) |

where  is the diameter of the telescope's objective aperture. Thus, the minimum angular resolution of the

telescope is

is the diameter of the telescope's objective aperture. Thus, the minimum angular resolution of the

telescope is

|

(10.87) |

which is a slightly more accurate version of the criterion given in Section 10.7.

-direction, which is normally incident on an opaque

screen that occupies the plane

-direction, which is normally incident on an opaque

screen that occupies the plane  . Suppose that there is an irregularly shaped aperture cut in the screen, and

that the light that passes through this aperture travels to a flat projection screen occupying the plane

. Suppose that there is an irregularly shaped aperture cut in the screen, and

that the light that passes through this aperture travels to a flat projection screen occupying the plane  .

We wish to determine the interference/diffraction pattern that appears on the projection screen, as a function of the size

and shape of the aperture. We can achieve this goal by employing a modified

version of Huygen's principle. In Section 10.6, we

divided the aperture into infinitesimal parallel strips of equal height, and argued that each

strip emits a cylindrical wave in the forward direction that has the same amplitude and phase as the

light that illuminates it from behind. For the case of an irregularly shaped aperture, we can similarly divide the aperture into

infinitesimal squares of equal area, and argue that each square emits a spherical wave in the forward direction that has the

same amplitude and phase as the light that illuminates it from behind. [Recall that line sources and point sources emit

cylindrical and spherical waves, respectively. (See Sections 7.4 and 7.5.)]

Using analogous arguments to those employed in Section 10.2, we can show that

provided

.

We wish to determine the interference/diffraction pattern that appears on the projection screen, as a function of the size

and shape of the aperture. We can achieve this goal by employing a modified

version of Huygen's principle. In Section 10.6, we

divided the aperture into infinitesimal parallel strips of equal height, and argued that each

strip emits a cylindrical wave in the forward direction that has the same amplitude and phase as the

light that illuminates it from behind. For the case of an irregularly shaped aperture, we can similarly divide the aperture into

infinitesimal squares of equal area, and argue that each square emits a spherical wave in the forward direction that has the

same amplitude and phase as the light that illuminates it from behind. [Recall that line sources and point sources emit

cylindrical and spherical waves, respectively. (See Sections 7.4 and 7.5.)]

Using analogous arguments to those employed in Section 10.2, we can show that

provided

is the characteristic size of the aperture, and

is the characteristic size of the aperture, and  is the wavelength of the light that illuminates it from behind, we are

in the far-field limit. In this limit, the interference/diffraction pattern appearing on the projection screen is entirely due to the phase

differences between the spherical waves that travel to a given point on the screen from different parts of the aperture. These

phase differences are produced by the slightly different distances traveled by these waves.

is the wavelength of the light that illuminates it from behind, we are

in the far-field limit. In this limit, the interference/diffraction pattern appearing on the projection screen is entirely due to the phase

differences between the spherical waves that travel to a given point on the screen from different parts of the aperture. These

phase differences are produced by the slightly different distances traveled by these waves.

,

,  ,

,  in the aperture that travels to the point

in the aperture that travels to the point

,

,  ,

,  on the projection screen. The distance traveled by this wave is

on the projection screen. The distance traveled by this wave is

and

and

are the angular coordinates of the point on the projection screen. Here, we are assuming that

are the angular coordinates of the point on the projection screen. Here, we are assuming that

,

,  on the projection screen is a linear superposition of the spherical waves that travel to it from all

parts of the aperture. It follows that

Here,

on the projection screen is a linear superposition of the spherical waves that travel to it from all

parts of the aperture. It follows that

Here,  is an aperture function that takes the value

is an aperture function that takes the value  in the unblocked parts of the opaque screen, where

in the unblocked parts of the opaque screen, where  is the aperture area, and the

value zero in the blocked parts. We have neglected the

is the aperture area, and the

value zero in the blocked parts. We have neglected the  variation of the wave amplitudes (see Section 7.5)

because we are working in the far-field limit. It follows, from Equations (10.71) and (10.73), that

Here, we have made use of the fact that

variation of the wave amplitudes (see Section 7.5)

because we are working in the far-field limit. It follows, from Equations (10.71) and (10.73), that

Here, we have made use of the fact that

,

,

, and have also assumed that the aperture function is an even function of

both

, and have also assumed that the aperture function is an even function of

both  and

and  (i.e., the aperture is symmetric about

(i.e., the aperture is symmetric about  and

and  ). The intensity of the light at the point

). The intensity of the light at the point  ,

,  on the

projection screen is thus

on the

projection screen is thus

![$\displaystyle {\cal I}(\theta_x,\theta_y)\propto \langle \psi^{\,2}(\theta_x,\t...

...infty}^\infty F(x,y)\,\cos(k\,\theta_x\,x+k\,\theta_y\,y)\,dx\,dy\right]^{\,2}.$](img3509.png)

![\includegraphics[width=0.8\textwidth]{Chapter10/fig10_13.eps}](img3510.png)

and

and

in the

in the  -

- plane.

The intensity of the interference/diffraction pattern on the projection screen produced by such an aperture is

plane.

The intensity of the interference/diffraction pattern on the projection screen produced by such an aperture is

![$\displaystyle {\cal I}(\theta_x,\theta_y)\propto \left[\int_{-b/2}^{b/2}\int_{-...

...2}\cos(k\,\theta_x\,x+k\,\theta_y\,y)\,\frac{dx}{a}\,\frac{dy}{b}\right]^{\,2},$](img3514.png)

and

and

, surrounded by much weaker secondary maxima arranged on a rectangular grid. Incidentally, our assumption that

, surrounded by much weaker secondary maxima arranged on a rectangular grid. Incidentally, our assumption that

,

,

is only

self-consistent provided

is only

self-consistent provided

,

,  (i.e., provided the wavelength of the light is much less than the dimensions of

the aperture).

(i.e., provided the wavelength of the light is much less than the dimensions of

the aperture).

in the

in the  -

- plane. Let

plane. Let

,

,

,

,

, and

, and

. The

intensity of the interference/diffraction pattern on the projection screen produced by such an aperture is

. The

intensity of the interference/diffraction pattern on the projection screen produced by such an aperture is

![$\displaystyle {\cal I}(\theta,\phi') \propto\left(\int_0^a\int_0^{2\pi}\cos[k\,...

...theta\,\cos(\phi-\phi')]\,\frac{\rho\,d\phi\,d\rho}{\pi\,a^{\,2}}\right)^{\,2},$](img3526.png)

.

It is readily demonstrated that (Abramowitz and Stegun 1965)

.

It is readily demonstrated that (Abramowitz and Stegun 1965)

is the Bessel function of degree zero introduced in Section 7.6.

It follows that

is the Bessel function of degree zero introduced in Section 7.6.

It follows that

![$\displaystyle {\cal I}(\theta) \propto \left[\frac{2}{\pi\,a^{\,2}}\int_0^a J_0...

...ft[\frac{2}{(k\,\theta\,a)^2}\int_0^{k\theta\,a}

J_0(z')\,z'\,dz'\right]^{\,2}.$](img3530.png)

![$\displaystyle {\cal I}(\theta)\propto \left[\frac{2\,J_1(k\,a\,\theta)}{k\,a\,\theta}\right]^{\,2}.$](img3533.png)

, whereas Table 10.1 lists the first few values

of

, whereas Table 10.1 lists the first few values

of  at which this function is zero. Finally, Figure 10.15 shows the interference/diffraction pattern

associated with a circular aperture. The pattern consists of a central disk, known as an Airy disk,

surrounded by much fainter concentric rings. The angular radius of the Airy disk is

at which this function is zero. Finally, Figure 10.15 shows the interference/diffraction pattern

associated with a circular aperture. The pattern consists of a central disk, known as an Airy disk,

surrounded by much fainter concentric rings. The angular radius of the Airy disk is

where

where

is the first zero of the function

is the first zero of the function

. It follows that

. It follows that

is the diameter of the aperture.

is the diameter of the aperture.

![\includegraphics[width=0.8\textwidth]{Chapter10/fig10_15.eps}](img3538.png)

, between the stars be greater than the angular radii of their Airy disks. This yields

, between the stars be greater than the angular radii of their Airy disks. This yields

is the diameter of the telescope's objective aperture. Thus, the minimum angular resolution of the

telescope is

is the diameter of the telescope's objective aperture. Thus, the minimum angular resolution of the

telescope is