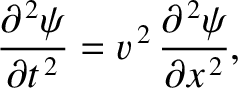

Consider the one-dimensional wave equation,

|

(8.33) |

where  is the wavefunction, and

is the wavefunction, and  the characteristic phase velocity. We have seen a number of

particular solutions of this equation. For instance,

the characteristic phase velocity. We have seen a number of

particular solutions of this equation. For instance,

|

(8.34) |

represents a traveling wave of amplitude  , angular frequency

, angular frequency  , wavenumber

, wavenumber  , and phase angle

, and phase angle  , that propagates in the positive

, that propagates in the positive  -direction.

The previous expression is a solution of the one-dimensional wave equation, (8.33), provided

that it satisfies the dispersion relation

-direction.

The previous expression is a solution of the one-dimensional wave equation, (8.33), provided

that it satisfies the dispersion relation

|

(8.35) |

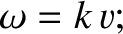

that is, provided the wave propagates at the fixed phase velocity  .

We can also write the wavefunction (8.34) in the form

.

We can also write the wavefunction (8.34) in the form

![$\displaystyle \psi(x,t) = C_+\,\cos[k\,(v\,t-x)] + S_+\,\sin[k\,(v\,t-x)],$](img2400.png) |

(8.36) |

where

,

,

, and we have explicitly incorporated the dispersion relation

, and we have explicitly incorporated the dispersion relation

into the solution. The previous expression can be regarded as the most general

form for a traveling wave of wavenumber

into the solution. The previous expression can be regarded as the most general

form for a traveling wave of wavenumber  propagating in the positive

propagating in the positive  -direction.

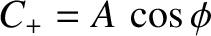

Likewise, the most general form for a traveling wave of wavenumber

-direction.

Likewise, the most general form for a traveling wave of wavenumber  propagating

in the negative

propagating

in the negative  -direction is

-direction is

![$\displaystyle \psi(x,t) = C_-\,\cos[k\,(v\,t+x)] + S_-\,\sin[k\,(v\,t+x)].$](img2403.png) |

(8.37) |

We have also encountered standing wave solutions of Equation (8.33).

However, as we have seen, these can be regarded as linear superpositions of traveling waves, of equal

amplitude and wavenumber, propagating in opposite directions. (See Section 6.4.)

In other words, standing waves are not fundamentally different to traveling waves.

The wave equation, (8.33), is linear. This suggests that its most

general solution can be written as a linear superposition of all of its valid

wavelike solutions. In the absence of specific boundary

conditions, there is no restriction on the possible wavenumbers of such solutions.

Thus, it is plausible that the most general solution of Equation (8.33) can be written

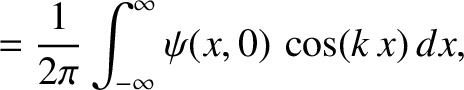

In other words, the general solution is a linear superposition of traveling waves propagating to the

right (i.e., in the positive  -direction), and to the left. Here,

-direction), and to the left. Here,  represents the amplitude of right-propagating cosine waves of wavenumber

represents the amplitude of right-propagating cosine waves of wavenumber  in this

superposition. Moreover,

in this

superposition. Moreover,  represents the amplitude of right-propagating sine waves of wavenumber

represents the amplitude of right-propagating sine waves of wavenumber  ,

,  the amplitude of left-propagating cosine waves,

and

the amplitude of left-propagating cosine waves,

and  the amplitude of left-propagating sine waves. Because each of these

waves is individually a solution of Equation (8.33), we are guaranteed, from the

linear nature of this equation, that the previous superposition is also a solution.

the amplitude of left-propagating sine waves. Because each of these

waves is individually a solution of Equation (8.33), we are guaranteed, from the

linear nature of this equation, that the previous superposition is also a solution.

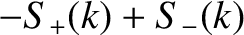

But, how can we prove that Equation (8.38) is the most general solution of the

wave equation, (8.33)? Our understanding of Newtonian dynamics

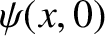

tells us that if we know the initial wave amplitude  , and its

time derivative

, and its

time derivative

, then this should constitute sufficient information to uniquely

specify the solution at all subsequent times. Hence, if

Equation (8.38) is the most general solution of Equation (8.33) then it must

be consistent with any initial wave amplitude, and any initial wave velocity. In

other words, given any

, then this should constitute sufficient information to uniquely

specify the solution at all subsequent times. Hence, if

Equation (8.38) is the most general solution of Equation (8.33) then it must

be consistent with any initial wave amplitude, and any initial wave velocity. In

other words, given any  and

and

, we should be

able to uniquely determine the functions

, we should be

able to uniquely determine the functions  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and

appearing in Equation (8.38). Let us see if this is the case.

appearing in Equation (8.38). Let us see if this is the case.

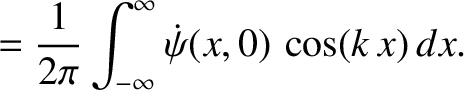

From Equation (8.38),

![$\displaystyle \psi(x,0) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\left[C_+(k)+C_-(k)\right]\,\cos(k\,x)\,dk+ \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\left[-S_+(k)+S_-(k)\right]\,\sin(k\,x)\,dk.$](img2413.png) |

(8.39) |

![$\displaystyle \dot{\psi}(x,0) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}k\,v\left[C_+(k)-C_-(k)\...

...,x)\,dk+ \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}k\,v\left[S_+(k)+S_-(k)\right]\,\cos(k\,x)\,dk.$](img2418.png) |

(8.42) |

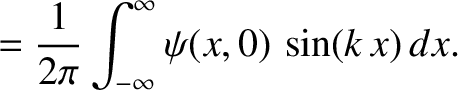

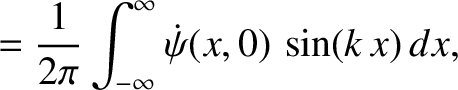

|

![$\displaystyle =\frac{1}{4\pi}\left[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\psi(x,0)\,\cos(k\,x)\,dx

+ \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\dot{\psi}(x,0)}{k\,v}\,\sin(k\,x)\,dx\right],$](img2424.png) |

(8.45) |

|

![$\displaystyle =\frac{1}{4\pi}\left[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\psi(x,0)\,\cos(k\,x)\,dx

- \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\dot{\psi}(x,0)}{k\,v}\,\sin(k\,x)\,dx\right],$](img2426.png) |

(8.46) |

|

![$\displaystyle =\frac{1}{4\pi}\left[-\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\psi(x,0)\,\sin(k\,x)\,dx

+ \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\dot{\psi}(x,0)}{k\,v}\,\cos(k\,x)\,dx\right],$](img2428.png) |

(8.47) |

|

![$\displaystyle =\frac{1}{4\pi}\left[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\psi(x,0)\,\sin(k\,x)\,dx

+\int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\dot{\psi}(x,0)}{k\,v}\,\cos(k\,x)\,dx\right].$](img2430.png) |

(8.48) |

,

,  ,

,

, and

, and  , appearing in Equation (8.38), for any

, appearing in Equation (8.38), for any  and

and

. This proves that Equation (8.38) is indeed the most general

solution of the wave equation, (8.33).

. This proves that Equation (8.38) is indeed the most general

solution of the wave equation, (8.33).

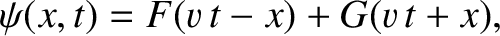

Let us examine our solution in more detail. Equation (8.38) can be

written

|

(8.49) |

where

(See Exercise 6.)

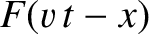

What is the significance of Equation (8.49)? Actually,  represents a wave disturbance of arbitrary

shape that propagates in the positive

represents a wave disturbance of arbitrary

shape that propagates in the positive  -direction, at the fixed speed

-direction, at the fixed speed  , without changing shape. This follows because a point with a given amplitude on the

wave,

, without changing shape. This follows because a point with a given amplitude on the

wave,

, has an equation of motion

, has an equation of motion

, and thus

propagates in the positive

, and thus

propagates in the positive  -direction at the speed

-direction at the speed  . Moreover,

because all points on the wave propagate in the same direction at the same speed,

it follows that the wave does not change shape as it moves. By analogy,

. Moreover,

because all points on the wave propagate in the same direction at the same speed,

it follows that the wave does not change shape as it moves. By analogy,

represents a wave disturbance of arbitrary shape that propagates in the

negative

represents a wave disturbance of arbitrary shape that propagates in the

negative  -direction, at the fixed speed

-direction, at the fixed speed  , without changing shape.

We conclude that the most general solution to the wave equation, (8.33), is

a superposition of two wave disturbances of arbitrary shapes that propagate

in opposite directions, at the fixed speed

, without changing shape.

We conclude that the most general solution to the wave equation, (8.33), is

a superposition of two wave disturbances of arbitrary shapes that propagate

in opposite directions, at the fixed speed  , without changing shape. Such

solutions are generally termed wave pulses. What is the relationship

between a general wave pulse and the sinusoidal traveling wave solutions to the

wave equation that we found previously? As is apparent from Equations (8.50) and (8.51), a wave pulse is a superposition of sinusoidal

traveling waves propagating in the same direction as the pulse. Moreover, the amplitude of cosine

waves of wavenumber

, without changing shape. Such

solutions are generally termed wave pulses. What is the relationship

between a general wave pulse and the sinusoidal traveling wave solutions to the

wave equation that we found previously? As is apparent from Equations (8.50) and (8.51), a wave pulse is a superposition of sinusoidal

traveling waves propagating in the same direction as the pulse. Moreover, the amplitude of cosine

waves of wavenumber  in this superposition is the cosine Fourier

transform of the pulse shape, evaluated at wavenumber

in this superposition is the cosine Fourier

transform of the pulse shape, evaluated at wavenumber  . Likewise,

the amplitude of sine waves of wavenumber

. Likewise,

the amplitude of sine waves of wavenumber  in the superposition is the sine Fourier

transform of the pulse shape, evaluated at wavenumber

in the superposition is the sine Fourier

transform of the pulse shape, evaluated at wavenumber  .

.

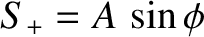

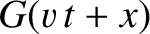

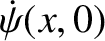

Figure 8.3:

Fourier transform of a triangular wave pulse.

|

|

For instance, suppose that we have a triangular wave pulse of the form

![\begin{displaymath}F(x) = \left\{

\begin{array}{lcc}

1 -2\,\vert x\vert/l&\mbox{...

...vert\leq l/2\\ [0.5ex]

0 &&\vert x\vert>l/2

\end{array}\right..\end{displaymath}](img2441.png) |

(8.52) |

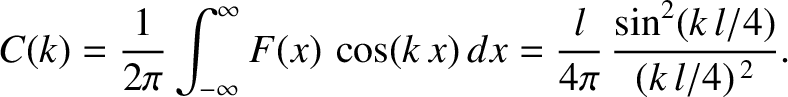

The sine Fourier transform of this pulse shape is zero by symmetry. However, the

cosine Fourier transform is

|

(8.53) |

(See Exercise 7.)

The functions  and

and  are shown in Figure 8.3.

It follows that the right-propagating triangular wave pulse

are shown in Figure 8.3.

It follows that the right-propagating triangular wave pulse

![\begin{displaymath}\psi(x,t)= \left\{

\begin{array}{lcc}

1 -2\,\vert v\,t-x\vert...

...\leq l/2\\ [0.5ex]

0 &&\vert v\,t-x\vert>l/2

\end{array}\right.\end{displaymath}](img2443.png) |

(8.54) |

can be written as the following superposition of right-propagating cosine waves:

![$\displaystyle \psi(x,t) =\frac{1}{4\pi} \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\sin^2(k\,l/4)}{(k\,l/4)^{\,2}}\,\cos[k\,(v\,t-x)]\,l\,dk.$](img2444.png) |

(8.55) |

Likewise, the left-propagating triangular wave pulse

![\begin{displaymath}\psi(x,t)= \left\{

\begin{array}{ccc}

1 -2\,\vert v\,t+x\vert...

...\leq l/2\\ [0.5ex]

0 &&\vert v\,t+x\vert>l/2

\end{array}\right.\end{displaymath}](img2445.png) |

(8.56) |

becomes

![$\displaystyle \psi(x,t) =\frac{1}{4\pi} \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\sin^2(k\,l/4)}{(k\,l/4)^{\,2}}\,\cos[k\,(v\,t+x)]\,l\,dk.$](img2446.png) |

(8.57) |

The ideas developed in this section can be extended to multi-dimensional waves in a straightforward

fashion. (See Exercises 12 and 13.)

is the wavefunction, and

is the wavefunction, and  the characteristic phase velocity. We have seen a number of

particular solutions of this equation. For instance,

represents a traveling wave of amplitude

the characteristic phase velocity. We have seen a number of

particular solutions of this equation. For instance,

represents a traveling wave of amplitude  , angular frequency

, angular frequency  , wavenumber

, wavenumber  , and phase angle

, and phase angle  , that propagates in the positive

, that propagates in the positive  -direction.

The previous expression is a solution of the one-dimensional wave equation, (8.33), provided

that it satisfies the dispersion relation

-direction.

The previous expression is a solution of the one-dimensional wave equation, (8.33), provided

that it satisfies the dispersion relation

.

We can also write the wavefunction (8.34) in the form

.

We can also write the wavefunction (8.34) in the form

![$\displaystyle \psi(x,t) = C_+\,\cos[k\,(v\,t-x)] + S_+\,\sin[k\,(v\,t-x)],$](img2400.png)

,

,

, and we have explicitly incorporated the dispersion relation

, and we have explicitly incorporated the dispersion relation

into the solution. The previous expression can be regarded as the most general

form for a traveling wave of wavenumber

into the solution. The previous expression can be regarded as the most general

form for a traveling wave of wavenumber  propagating in the positive

propagating in the positive  -direction.

Likewise, the most general form for a traveling wave of wavenumber

-direction.

Likewise, the most general form for a traveling wave of wavenumber  propagating

in the negative

propagating

in the negative  -direction is

-direction is

![$\displaystyle \psi(x,t) = C_-\,\cos[k\,(v\,t+x)] + S_-\,\sin[k\,(v\,t+x)].$](img2403.png)

-direction), and to the left. Here,

-direction), and to the left. Here,  represents the amplitude of right-propagating cosine waves of wavenumber

represents the amplitude of right-propagating cosine waves of wavenumber  in this

superposition. Moreover,

in this

superposition. Moreover,  represents the amplitude of right-propagating sine waves of wavenumber

represents the amplitude of right-propagating sine waves of wavenumber  ,

,  the amplitude of left-propagating cosine waves,

and

the amplitude of left-propagating cosine waves,

and  the amplitude of left-propagating sine waves. Because each of these

waves is individually a solution of Equation (8.33), we are guaranteed, from the

linear nature of this equation, that the previous superposition is also a solution.

the amplitude of left-propagating sine waves. Because each of these

waves is individually a solution of Equation (8.33), we are guaranteed, from the

linear nature of this equation, that the previous superposition is also a solution.

, and its

time derivative

, and its

time derivative

, then this should constitute sufficient information to uniquely

specify the solution at all subsequent times. Hence, if

Equation (8.38) is the most general solution of Equation (8.33) then it must

be consistent with any initial wave amplitude, and any initial wave velocity. In

other words, given any

, then this should constitute sufficient information to uniquely

specify the solution at all subsequent times. Hence, if

Equation (8.38) is the most general solution of Equation (8.33) then it must

be consistent with any initial wave amplitude, and any initial wave velocity. In

other words, given any  and

and

, we should be

able to uniquely determine the functions

, we should be

able to uniquely determine the functions  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and

appearing in Equation (8.38). Let us see if this is the case.

appearing in Equation (8.38). Let us see if this is the case.

![$\displaystyle \psi(x,0) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\left[C_+(k)+C_-(k)\right]\,\cos(k\,x)\,dk+ \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\left[-S_+(k)+S_-(k)\right]\,\sin(k\,x)\,dk.$](img2413.png)

![$\displaystyle \dot{\psi}(x,0) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}k\,v\left[C_+(k)-C_-(k)\...

...,x)\,dk+ \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}k\,v\left[S_+(k)+S_-(k)\right]\,\cos(k\,x)\,dk.$](img2418.png)

![$\displaystyle k\,v\,[C_+(k) - C_-(k)]$](img2419.png)

![$\displaystyle k\,v\,[S_+(k) + S_-(k)]$](img2421.png)

![$\displaystyle =\frac{1}{4\pi}\left[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\psi(x,0)\,\cos(k\,x)\,dx

+ \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\dot{\psi}(x,0)}{k\,v}\,\sin(k\,x)\,dx\right],$](img2424.png)

![$\displaystyle =\frac{1}{4\pi}\left[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\psi(x,0)\,\cos(k\,x)\,dx

- \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\dot{\psi}(x,0)}{k\,v}\,\sin(k\,x)\,dx\right],$](img2426.png)

![$\displaystyle =\frac{1}{4\pi}\left[-\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\psi(x,0)\,\sin(k\,x)\,dx

+ \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\dot{\psi}(x,0)}{k\,v}\,\cos(k\,x)\,dx\right],$](img2428.png)

![$\displaystyle =\frac{1}{4\pi}\left[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\psi(x,0)\,\sin(k\,x)\,dx

+\int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\dot{\psi}(x,0)}{k\,v}\,\cos(k\,x)\,dx\right].$](img2430.png)

,

,  ,

,

, and

, and  , appearing in Equation (8.38), for any

, appearing in Equation (8.38), for any  and

and

. This proves that Equation (8.38) is indeed the most general

solution of the wave equation, (8.33).

. This proves that Equation (8.38) is indeed the most general

solution of the wave equation, (8.33).

represents a wave disturbance of arbitrary

shape that propagates in the positive

represents a wave disturbance of arbitrary

shape that propagates in the positive  -direction, at the fixed speed

-direction, at the fixed speed  , without changing shape. This follows because a point with a given amplitude on the

wave,

, without changing shape. This follows because a point with a given amplitude on the

wave,

, has an equation of motion

, has an equation of motion

, and thus

propagates in the positive

, and thus

propagates in the positive  -direction at the speed

-direction at the speed  . Moreover,

because all points on the wave propagate in the same direction at the same speed,

it follows that the wave does not change shape as it moves. By analogy,

. Moreover,

because all points on the wave propagate in the same direction at the same speed,

it follows that the wave does not change shape as it moves. By analogy,

represents a wave disturbance of arbitrary shape that propagates in the

negative

represents a wave disturbance of arbitrary shape that propagates in the

negative  -direction, at the fixed speed

-direction, at the fixed speed  , without changing shape.

We conclude that the most general solution to the wave equation, (8.33), is

a superposition of two wave disturbances of arbitrary shapes that propagate

in opposite directions, at the fixed speed

, without changing shape.

We conclude that the most general solution to the wave equation, (8.33), is

a superposition of two wave disturbances of arbitrary shapes that propagate

in opposite directions, at the fixed speed  , without changing shape. Such

solutions are generally termed wave pulses. What is the relationship

between a general wave pulse and the sinusoidal traveling wave solutions to the

wave equation that we found previously? As is apparent from Equations (8.50) and (8.51), a wave pulse is a superposition of sinusoidal

traveling waves propagating in the same direction as the pulse. Moreover, the amplitude of cosine

waves of wavenumber

, without changing shape. Such

solutions are generally termed wave pulses. What is the relationship

between a general wave pulse and the sinusoidal traveling wave solutions to the

wave equation that we found previously? As is apparent from Equations (8.50) and (8.51), a wave pulse is a superposition of sinusoidal

traveling waves propagating in the same direction as the pulse. Moreover, the amplitude of cosine

waves of wavenumber  in this superposition is the cosine Fourier

transform of the pulse shape, evaluated at wavenumber

in this superposition is the cosine Fourier

transform of the pulse shape, evaluated at wavenumber  . Likewise,

the amplitude of sine waves of wavenumber

. Likewise,

the amplitude of sine waves of wavenumber  in the superposition is the sine Fourier

transform of the pulse shape, evaluated at wavenumber

in the superposition is the sine Fourier

transform of the pulse shape, evaluated at wavenumber  .

.

![\begin{displaymath}F(x) = \left\{

\begin{array}{lcc}

1 -2\,\vert x\vert/l&\mbox{...

...vert\leq l/2\\ [0.5ex]

0 &&\vert x\vert>l/2

\end{array}\right..\end{displaymath}](img2441.png)

and

and  are shown in Figure 8.3.

It follows that the right-propagating triangular wave pulse

are shown in Figure 8.3.

It follows that the right-propagating triangular wave pulse

![\begin{displaymath}\psi(x,t)= \left\{

\begin{array}{lcc}

1 -2\,\vert v\,t-x\vert...

...\leq l/2\\ [0.5ex]

0 &&\vert v\,t-x\vert>l/2

\end{array}\right.\end{displaymath}](img2443.png)

![$\displaystyle \psi(x,t) =\frac{1}{4\pi} \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\sin^2(k\,l/4)}{(k\,l/4)^{\,2}}\,\cos[k\,(v\,t-x)]\,l\,dk.$](img2444.png)

![\begin{displaymath}\psi(x,t)= \left\{

\begin{array}{ccc}

1 -2\,\vert v\,t+x\vert...

...\leq l/2\\ [0.5ex]

0 &&\vert v\,t+x\vert>l/2

\end{array}\right.\end{displaymath}](img2445.png)

![$\displaystyle \psi(x,t) =\frac{1}{4\pi} \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\sin^2(k\,l/4)}{(k\,l/4)^{\,2}}\,\cos[k\,(v\,t+x)]\,l\,dk.$](img2446.png)