In steady-state, the current ![]() flowing around the the circuit has the magnitude

flowing around the the circuit has the magnitude

| (254) |

Let us now slightly modify our ![]() circuit by introducing a switch.

The new circuit is shown in Fig. 46. Suppose that the switch is initially open, but is

suddenly closed

at

circuit by introducing a switch.

The new circuit is shown in Fig. 46. Suppose that the switch is initially open, but is

suddenly closed

at ![]() . Obviously, we expect the instantaneous current

. Obviously, we expect the instantaneous current ![]() which flows

around the circuit, once the switch is thrown, to eventually settle

down to the steady-state

value

which flows

around the circuit, once the switch is thrown, to eventually settle

down to the steady-state

value ![]() . But, how long does this process take? Note that as the current flowing around

the circuit is building up to its final value, a non-zero back-emf is generated in the

inductor, according to Eq. (243). Thus, although the inductor does not

affect the final steady-state value of the current flowing around the circuit,

it certainly does affect how long after the switch is closed it takes

for this final current to be established.

. But, how long does this process take? Note that as the current flowing around

the circuit is building up to its final value, a non-zero back-emf is generated in the

inductor, according to Eq. (243). Thus, although the inductor does not

affect the final steady-state value of the current flowing around the circuit,

it certainly does affect how long after the switch is closed it takes

for this final current to be established.

If the instantaneous current ![]() flowing around the circuit changes by an

amount

flowing around the circuit changes by an

amount ![]() in a short time interval

in a short time interval ![]() , then the

emf generated in the inductor is given by [see Eq. (243)]

, then the

emf generated in the inductor is given by [see Eq. (243)]

| (255) |

| (256) |

Integration of Eq. (259), subject to the initial condition

(260), yields

| (261) |

| (262) |

| (263) |

Suppose that the current flowing in the circuit discussed above has settled

down to its steady-state value ![]() .

Consider what would happen

if we were to suddenly (at

.

Consider what would happen

if we were to suddenly (at ![]() , say) switch the battery out

of the circuit, and replace it by a conducting wire. Obviously,

we would expect the current to

eventually decay away to zero, since there is no longer a steady emf in the circuit

to maintain a steady current. But, how long does this process take?

, say) switch the battery out

of the circuit, and replace it by a conducting wire. Obviously,

we would expect the current to

eventually decay away to zero, since there is no longer a steady emf in the circuit

to maintain a steady current. But, how long does this process take?

Applying Ohm's law around the circuit, in the absence of the battery,

we obtain

| (264) |

Integration of Eq. (265), subject to the boundary condition (266), yields

| (267) |

We can now appreciate the significance of self inductance. The back-emf

generated in an inductor, as the current flowing through it

tries to change, effectively prevents the

current from rising (or falling) much faster than the L/R time of the

circuit. This effect is

sometimes advantageous, but is often a great nuisance.

All circuits possess some self inductance, as well as some resistance, so

all have a finite ![]() time. This means that when we power up a DC circuit, the current

does not jump up instantaneously to its steady-state value. Instead, the

rise is spread out over the

time. This means that when we power up a DC circuit, the current

does not jump up instantaneously to its steady-state value. Instead, the

rise is spread out over the ![]() time of the circuit. This is a good thing.

If the current were to rise instantaneously then extremely large

inductive electric

fields would be generated by the sudden jump in the magnetic field, leading,

inevitably, to breakdown and electric arcing. So, if there were no such thing

as self inductance then every time we switched a DC electric circuit on or off

there would be a big blue flash due to arcing between

conductors. Self inductance

can also be a bad thing. Suppose that we possess a fancy power supply, and wish

to use it to send an electric signal down a wire.

Of course, the wire will possess both resistance and inductance,

and will, therefore, have some characteristic

time of the circuit. This is a good thing.

If the current were to rise instantaneously then extremely large

inductive electric

fields would be generated by the sudden jump in the magnetic field, leading,

inevitably, to breakdown and electric arcing. So, if there were no such thing

as self inductance then every time we switched a DC electric circuit on or off

there would be a big blue flash due to arcing between

conductors. Self inductance

can also be a bad thing. Suppose that we possess a fancy power supply, and wish

to use it to send an electric signal down a wire.

Of course, the wire will possess both resistance and inductance,

and will, therefore, have some characteristic ![]() time. Suppose that we

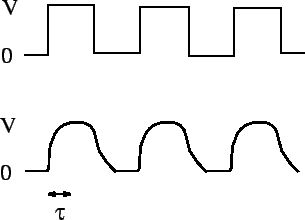

try to send a square-wave signal down the wire. Since the current in the wire

cannot rise or fall faster than the

time. Suppose that we

try to send a square-wave signal down the wire. Since the current in the wire

cannot rise or fall faster than the ![]() time, the leading and trailing edges of

the signal get smoothed out over an

time, the leading and trailing edges of

the signal get smoothed out over an ![]() time. The typical difference between

the signal fed into the wire (upper trace) and that which comes out of the

other end (lower trace) is illustrated in Fig. 48. Clearly, there is little

point in us having a fancy power supply unless we also possess a low inductance

wire, so that the signal from the power supply can be

transmitted to some load device without serious distortion.

time. The typical difference between

the signal fed into the wire (upper trace) and that which comes out of the

other end (lower trace) is illustrated in Fig. 48. Clearly, there is little

point in us having a fancy power supply unless we also possess a low inductance

wire, so that the signal from the power supply can be

transmitted to some load device without serious distortion.

|