Next: Satellite orbits

Up: Orbital motion

Previous: Gravity

We saw earlier, in Sect. 5.5, that gravity is a conservative force, and, therefore,

has an associated potential energy. Let us obtain a general formula for this energy.

Consider a point object of mass  , which is a radial distance

, which is a radial distance  from another point

object of mass

from another point

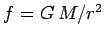

object of mass  . The gravitational force acting on the first mass is

of magnitude

. The gravitational force acting on the first mass is

of magnitude  , and is directed towards the second mass. Imagine that the

first mass moves radially away from the second mass, until it reaches infinity. What is

the change in the potential energy of the first mass associated with this shift?

According to Eq. (155),

, and is directed towards the second mass. Imagine that the

first mass moves radially away from the second mass, until it reaches infinity. What is

the change in the potential energy of the first mass associated with this shift?

According to Eq. (155),

![\begin{displaymath}

U(\infty) - U(r) = -\int_{r}^\infty [-f(r)] dr.

\end{displaymath}](img1936.png) |

(550) |

There is a minus sign in front of  because this force is oppositely directed to the motion.

The above expression can be integrated to give

because this force is oppositely directed to the motion.

The above expression can be integrated to give

|

(551) |

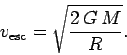

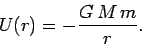

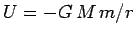

Here, we have adopted the convenient normalization that the potential energy at infinity is

zero. According to the above formula, the gravitational potential energy of a mass  located a distance

located a distance  from a mass

from a mass  is simply

is simply  .

.

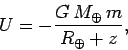

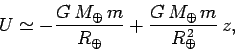

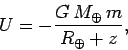

Consider an object of mass  moving close to the Earth's surface. The potential

energy of such an object can be written

moving close to the Earth's surface. The potential

energy of such an object can be written

|

(552) |

where  and

and  are the mass and radius of the Earth, respectively, and

are the mass and radius of the Earth, respectively, and

is the vertical height of the object above the Earth's surface. In the limit that

is the vertical height of the object above the Earth's surface. In the limit that

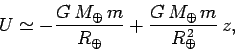

, the above expression can be expanded using the binomial theorem

to give

, the above expression can be expanded using the binomial theorem

to give

|

(553) |

Since potential energy is undetermined to an arbitrary additive constant, we could just as

well write

|

(554) |

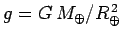

where

is the acceleration due to gravity at

the Earth's surface [see Eq. (548)]. Of course, the above formula is equivalent

to the formula (125) derived earlier on in this course.

is the acceleration due to gravity at

the Earth's surface [see Eq. (548)]. Of course, the above formula is equivalent

to the formula (125) derived earlier on in this course.

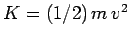

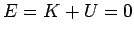

For an object of mass  and speed

and speed  , moving in the gravitational field of a fixed object

of mass

, moving in the gravitational field of a fixed object

of mass  , we expect the total energy,

, we expect the total energy,

|

(555) |

to be a constant of the motion. Here, the kinetic energy is written

, whereas

the potential energy takes the form

, whereas

the potential energy takes the form

. Of course,

. Of course,  is the distance between the

two objects. Suppose that the fixed object is a sphere of radius

is the distance between the

two objects. Suppose that the fixed object is a sphere of radius  . Suppose,

further, that the second object is launched from the surface of this sphere

with some velocity

. Suppose,

further, that the second object is launched from the surface of this sphere

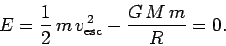

with some velocity  which is such that it only just escapes the sphere's gravitational

influence. After the object has escaped, it is a long way away from the sphere, and hence

which is such that it only just escapes the sphere's gravitational

influence. After the object has escaped, it is a long way away from the sphere, and hence

. Moreover, if the object only just escaped, then we also expect

. Moreover, if the object only just escaped, then we also expect  , since the

object will have expended all of its initial kinetic energy escaping from the sphere's

gravitational well. We conclude that our object possesses zero net energy:

i.e.,

, since the

object will have expended all of its initial kinetic energy escaping from the sphere's

gravitational well. We conclude that our object possesses zero net energy:

i.e.,  . Since

. Since  is a constant of the motion, it follows

that at the launch point

is a constant of the motion, it follows

that at the launch point

|

(556) |

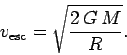

This expression can be rearranged to give

|

(557) |

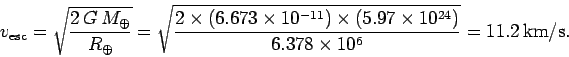

The quantity  is known as the escape velocity. Objects launched from

the surface of the sphere with velocities exceeding this value will eventually

escape from the sphere's gravitational influence. Otherwise, the objects

will remain in orbit around the sphere, and may eventually strike its surface.

Note that the escape velocity is independent of the object's mass and launch

direction (assuming that it is not straight into the sphere).

is known as the escape velocity. Objects launched from

the surface of the sphere with velocities exceeding this value will eventually

escape from the sphere's gravitational influence. Otherwise, the objects

will remain in orbit around the sphere, and may eventually strike its surface.

Note that the escape velocity is independent of the object's mass and launch

direction (assuming that it is not straight into the sphere).

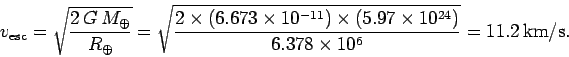

The escape velocity for the Earth is

|

(558) |

Clearly, NASA must launch deep space probes from the surface of the Earth with velocities which exceed this value if they are

to have any hope of eventually reaching their targets.

Next: Satellite orbits

Up: Orbital motion

Previous: Gravity

Richard Fitzpatrick

2006-02-02

![]() moving close to the Earth's surface. The potential

energy of such an object can be written

moving close to the Earth's surface. The potential

energy of such an object can be written

![]() and speed

and speed ![]() , moving in the gravitational field of a fixed object

of mass

, moving in the gravitational field of a fixed object

of mass ![]() , we expect the total energy,

, we expect the total energy,