Consider a system in a state ![]() that evolves in time. At time

that evolves in time. At time

![]() , the state of the system is represented by the ket

, the state of the system is represented by the ket

![]() . The label

. The label

![]() is needed to distinguish this ket from any other ket (

is needed to distinguish this ket from any other ket (

![]() , say)

that is evolving in time. The label

, say)

that is evolving in time. The label ![]() is needed to distinguish the different

states of the system at different times.

is needed to distinguish the different

states of the system at different times.

The final state of the system at time ![]() is completely determined by its

initial state at time

is completely determined by its

initial state at time ![]() plus the time interval

plus the time interval ![]() (assuming that

the system is left undisturbed during this time interval). However, the

final state only determines the direction of the final state ket.

Even if we adopt the convention that all state kets have unit norms,

the final ket is still not completely determined, because it can be multiplied

by an arbitrary

phase-factor. However, we expect that if a superposition relation

holds for certain states at time

(assuming that

the system is left undisturbed during this time interval). However, the

final state only determines the direction of the final state ket.

Even if we adopt the convention that all state kets have unit norms,

the final ket is still not completely determined, because it can be multiplied

by an arbitrary

phase-factor. However, we expect that if a superposition relation

holds for certain states at time ![]() then the same relation

should hold between the corresponding time-evolved states at time

then the same relation

should hold between the corresponding time-evolved states at time ![]() , assuming

that the system is left undisturbed between times

, assuming

that the system is left undisturbed between times ![]() and

and ![]() .

In other words,

if

.

In other words,

if

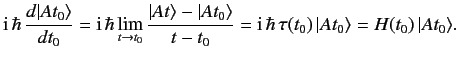

According to Equations (220) and (221), the final ket

![]() depends linearly

on the initial ket

depends linearly

on the initial ket

![]() . Thus, the final ket can be regarded as the

result of some linear operator acting on the initial ket: i.e.,

. Thus, the final ket can be regarded as the

result of some linear operator acting on the initial ket: i.e.,

Because we have adopted a convention in which the norm of any state ket is unity,

it make sense to define the time evolution operator ![]() in such a manner that

it preserves the length of any ket upon which it acts

(i.e., if a ket is properly normalized at time

in such a manner that

it preserves the length of any ket upon which it acts

(i.e., if a ket is properly normalized at time ![]() then it will remain normalized at

all subsequent times

then it will remain normalized at

all subsequent times ![]() ).

This is always possible,

because the length of a ket possesses no physical significance. Thus,

we require that

).

This is always possible,

because the length of a ket possesses no physical significance. Thus,

we require that

| (223) |

Up to now, the time evolution operator ![]() looks very much like the

spatial displacement

operator

looks very much like the

spatial displacement

operator ![]() introduced in the previous section. However, there are some

important differences between time evolution and spatial displacement. In general,

we do expect the expectation value of some observable

introduced in the previous section. However, there are some

important differences between time evolution and spatial displacement. In general,

we do expect the expectation value of some observable ![]() to

evolve with time, even if the system is left in a state of undisturbed motion

(after all, time evolution has no meaning unless something observable

changes with time). The triple product

to

evolve with time, even if the system is left in a state of undisturbed motion

(after all, time evolution has no meaning unless something observable

changes with time). The triple product

![]() can evolve

either because the ket

can evolve

either because the ket ![]() evolves and the operator

evolves and the operator ![]() stays constant,

the ket

stays constant,

the ket ![]() stays constant and the operator

stays constant and the operator ![]() evolves, or both

the ket

evolves, or both

the ket ![]() and the operator

and the operator ![]() evolve.

Because we are already committed to evolving state kets, according to Equation (222),

let us assume that the time evolution operator

evolve.

Because we are already committed to evolving state kets, according to Equation (222),

let us assume that the time evolution operator ![]() can be chosen in such a

manner that the operators representing the dynamical variables of the

system do not

evolve in time (unless they contain some specific time dependence).

can be chosen in such a

manner that the operators representing the dynamical variables of the

system do not

evolve in time (unless they contain some specific time dependence).

We expect, from physical continuity, that if

![]() then

then

![]() for any ket

for any ket ![]() . Thus, the

limit

. Thus, the

limit

| (227) |

|

(228) |

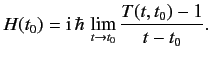

Equation (229) gives the general law for the time evolution of a state

ket in a scheme in which the operators representing the dynamical variables remain

fixed. This equation is denoted the Schrödinger equation of motion.

It involves a Hermitian operator ![]() which is, presumably, a characteristic

of the dynamical system under investigation.

which is, presumably, a characteristic

of the dynamical system under investigation.

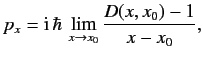

We saw, in Section 2.8, that

if the operator ![]() displaces the system along the

displaces the system along the ![]() -axis from

-axis from ![]() to

to ![]() then

then

|

(230) |

|

(231) |

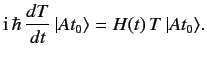

Substituting

![]() into Equation (229) yields

into Equation (229) yields

|

(232) |