Next: Fresnel Relations

Up: Wave Propagation in Inhomogeneous

Previous: Introduction

Laws of Geometric Optics

Suppose that the region  is occupied by a transparent dielectric medium of uniform refractive index

is occupied by a transparent dielectric medium of uniform refractive index  , whereas

the region

, whereas

the region  is occupied by a second transparent dielectric medium of uniform refractive index

is occupied by a second transparent dielectric medium of uniform refractive index  . (See Figure 14.) Let a plane light wave be launched toward positive

. (See Figure 14.) Let a plane light wave be launched toward positive  from a

light source of angular frequency

from a

light source of angular frequency  located at large negative

located at large negative  . Furthermore, suppose that this wave, which has the wavevector

. Furthermore, suppose that this wave, which has the wavevector  , is obliquely incident on the interface between the two media. We would expect the incident plane wave to be partially reflected and partially

refracted (i.e., transmitted) by the interface.

Let the reflected and refracted plane waves have the wavevectors

, is obliquely incident on the interface between the two media. We would expect the incident plane wave to be partially reflected and partially

refracted (i.e., transmitted) by the interface.

Let the reflected and refracted plane waves have the wavevectors

and

and  , respectively. (See Figure 14.) Hence, we can write

, respectively. (See Figure 14.) Hence, we can write

|

(946) |

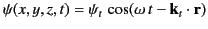

in the region  , and

, and

|

(947) |

in the region  . Here,

. Here,

represents the magnetic component of the resultant light wave,

represents the magnetic component of the resultant light wave,  the

amplitude of the incident wave,

the

amplitude of the incident wave,  the amplitude of the reflected wave, and

the amplitude of the reflected wave, and  the amplitude of the

refracted wave. All of the component waves have the same angular frequency,

the amplitude of the

refracted wave. All of the component waves have the same angular frequency,  , because this property is

ultimately determined by the wave source. Furthermore, if the magnetic component of an electromagnetic wave is specified then the electric

component of the wave is fully determined, and vice versa. (See Section 7.1.)

, because this property is

ultimately determined by the wave source. Furthermore, if the magnetic component of an electromagnetic wave is specified then the electric

component of the wave is fully determined, and vice versa. (See Section 7.1.)

In general, the wavefunction,  , must be continuous at

, must be continuous at  , because there cannot be a discontinuity in either the

normal or the tangential component of a magnetic field across an interface between two (non-magnetic) dielectric media. (The same is not true of an electric field, which can have a normal discontinuity across

an interface between two dielectric media.) This explains why we have chosen

, because there cannot be a discontinuity in either the

normal or the tangential component of a magnetic field across an interface between two (non-magnetic) dielectric media. (The same is not true of an electric field, which can have a normal discontinuity across

an interface between two dielectric media.) This explains why we have chosen  to represent the magnetic, rather than the electric,

component of the wave. Thus, the matching condition at

to represent the magnetic, rather than the electric,

component of the wave. Thus, the matching condition at  takes the form

takes the form

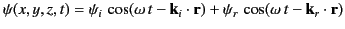

![$\displaystyle \psi_i\,\cos(\omega\,t-k_{i\,x}\,x-k_{i\,y}\,y)\\ [0.5ex] + \psi_...

...ga\,t-k_{r\,x}\,x-k_{r\,y}\,y)=\psi_t\,\cos(\omega\,t-k_{t\,x}\,x-k_{t\,y}\,y).$](img2024.png) |

(948) |

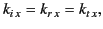

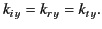

This condition must be satisfied at all values of  ,

,  , and

, and  . This is only possible if

. This is only possible if

|

(949) |

and

|

(950) |

Suppose that the direction of propagation of the incident wave lies in the  -

- plane, so that

plane, so that

. It immediately

follows, from Equation (951), that

. It immediately

follows, from Equation (951), that

. In other words, the directions of propagation of the reflected

and the refracted waves also lie in the

. In other words, the directions of propagation of the reflected

and the refracted waves also lie in the  -

- plane, which implies that

plane, which implies that  ,

,  and

and  are

co-planar vectors. This constraint is implicit in the well-known laws of

geometric optics.

are

co-planar vectors. This constraint is implicit in the well-known laws of

geometric optics.

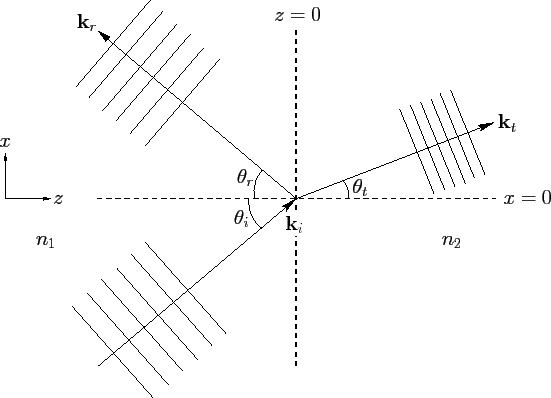

Figure 14:

Reflection and refraction of a plane wave at a plane boundary.

|

Assuming that the previously mentioned constraint is satisfied, let the incident, reflected, and refracted wave normals subtend

angles  ,

,  , and

, and  with the

with the  -axis, respectively. (See Figure 14.) It follows that

-axis, respectively. (See Figure 14.) It follows that

where

is the vacuum wavenumber, and

is the vacuum wavenumber, and  the velocity of light in vacuum.

Here, we have made use of the fact that wavenumber (i.e., the magnitude of the wavevector) of a light wave propagating through a dielectric medium of

refractive index

the velocity of light in vacuum.

Here, we have made use of the fact that wavenumber (i.e., the magnitude of the wavevector) of a light wave propagating through a dielectric medium of

refractive index  is

is  .

.

According to Equation (950),

, which yields

, which yields

|

(954) |

and

, which reduces to

, which reduces to

|

(955) |

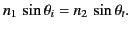

The first of these relations states that the angle of incidence,  , is equal to the angle of reflection,

, is equal to the angle of reflection,  . This is the

familiar law of reflection. Furthermore, the second relation corresponds to the equally familiar

law of refraction, otherwise known as Snell's law.

. This is the

familiar law of reflection. Furthermore, the second relation corresponds to the equally familiar

law of refraction, otherwise known as Snell's law.

Incidentally, the fact that a plane wave propagates through a uniform

dielectric medium with a constant wavevector, and, therefore, a constant direction of motion, is equivalent to the well-known law of rectilinear propagation, which

states that a light ray (i.e., the normal to a constant phase surface) propagates through a uniform medium in a straight-line.

It follows, from the previous discussion, that the laws of geometric optics (i.e., the law

of rectilinear propagation, the law of reflection, and the law of refraction) are fully consistent with the

wave properties of light, despite the fact that they do not seem to explicitly depend on these properties.

Next: Fresnel Relations

Up: Wave Propagation in Inhomogeneous

Previous: Introduction

Richard Fitzpatrick

2014-06-27

![]() , must be continuous at

, must be continuous at ![]() , because there cannot be a discontinuity in either the

normal or the tangential component of a magnetic field across an interface between two (non-magnetic) dielectric media. (The same is not true of an electric field, which can have a normal discontinuity across

an interface between two dielectric media.) This explains why we have chosen

, because there cannot be a discontinuity in either the

normal or the tangential component of a magnetic field across an interface between two (non-magnetic) dielectric media. (The same is not true of an electric field, which can have a normal discontinuity across

an interface between two dielectric media.) This explains why we have chosen ![]() to represent the magnetic, rather than the electric,

component of the wave. Thus, the matching condition at

to represent the magnetic, rather than the electric,

component of the wave. Thus, the matching condition at ![]() takes the form

takes the form

![]() -

-![]() plane, so that

plane, so that

![]() . It immediately

follows, from Equation (951), that

. It immediately

follows, from Equation (951), that

![]() . In other words, the directions of propagation of the reflected

and the refracted waves also lie in the

. In other words, the directions of propagation of the reflected

and the refracted waves also lie in the ![]() -

-![]() plane, which implies that

plane, which implies that ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() are

co-planar vectors. This constraint is implicit in the well-known laws of

geometric optics.

are

co-planar vectors. This constraint is implicit in the well-known laws of

geometric optics.

![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() with the

with the ![]() -axis, respectively. (See Figure 14.) It follows that

-axis, respectively. (See Figure 14.) It follows that

![]() , which yields

, which yields