Next: Faraday Rotation Up: Dispersive Waves Previous: Pulse Propagation Contents

and electric charge

and electric charge  interacting with a linearly polarized, sinusoidal,

electromagnetic plane wave that propagates in the

interacting with a linearly polarized, sinusoidal,

electromagnetic plane wave that propagates in the  -direction. Provided that the wave amplitude is not sufficiently large to

cause the particle to move at relativistic speeds, the electric

component of the wave exerts a much greater force on the particle than the magnetic

component. [This follows, from standard electrodynamics, because the ratio of the magnetic to the electric force is of order

-direction. Provided that the wave amplitude is not sufficiently large to

cause the particle to move at relativistic speeds, the electric

component of the wave exerts a much greater force on the particle than the magnetic

component. [This follows, from standard electrodynamics, because the ratio of the magnetic to the electric force is of order

,

where

,

where  is the amplitude of the wave electric field-strength,

is the amplitude of the wave electric field-strength,  the amplitude of the

wave magnetic field-strength,

the amplitude of the

wave magnetic field-strength,  the particle velocity, and

the particle velocity, and  the velocity of light in vacuum. Hence, the ratio of the forces is approximately

the velocity of light in vacuum. Hence, the ratio of the forces is approximately  (Fitzpatrick 2008).] Suppose that the electric component of the wave oscillates in the

(Fitzpatrick 2008).] Suppose that the electric component of the wave oscillates in the  -direction, and takes the form

where

-direction, and takes the form

where  is the wavenumber, and

is the wavenumber, and  the angular frequency.

The equation of motion of the particle is thus (see Appendix C)

where

the angular frequency.

The equation of motion of the particle is thus (see Appendix C)

where  measures its wave-induced displacement in the

measures its wave-induced displacement in the  -direction.

The previous equation can be solved to give

Thus, the wave causes the particle to execute sympathetic simple harmonic

oscillations, in the

-direction.

The previous equation can be solved to give

Thus, the wave causes the particle to execute sympathetic simple harmonic

oscillations, in the  -direction, with an amplitude that is directly proportional to its charge,

and inversely proportional to its mass.

-direction, with an amplitude that is directly proportional to its charge,

and inversely proportional to its mass.

Suppose that the wave is actually propagating through an unmagnetized, electrically neutral, plasma consisting

of free electrons, of mass  and charge

and charge  , and free ions, of mass

, and free ions, of mass  and charge

and charge  . Because the plasma is assumed to be electrically neutral, each species must have the same equilibrium number density,

. Because the plasma is assumed to be electrically neutral, each species must have the same equilibrium number density,

. Given that the electrons are much less massive than the ions (i.e.,

. Given that the electrons are much less massive than the ions (i.e.,

), but have the same charge (modulo a sign), it follows from Equation (9.21) that the wave-induced oscillations of the electrons

are of much higher amplitude than those of the ions. In fact, to a first approximation,

we can say that the electrons oscillate while the ions remain stationary.

Assuming that the electrons and ions are evenly distributed throughout the

plasma, the wave-induced displacement of an individual electron generates an effective electric

dipole moment in the

), but have the same charge (modulo a sign), it follows from Equation (9.21) that the wave-induced oscillations of the electrons

are of much higher amplitude than those of the ions. In fact, to a first approximation,

we can say that the electrons oscillate while the ions remain stationary.

Assuming that the electrons and ions are evenly distributed throughout the

plasma, the wave-induced displacement of an individual electron generates an effective electric

dipole moment in the  -direction of the form

-direction of the form

(the other component of the dipole is

a stationary ion of charge

(the other component of the dipole is

a stationary ion of charge  located at

located at  ).

Hence, the

).

Hence, the  -directed

electric dipole moment per unit volume is

-directed

electric dipole moment per unit volume is

and

and  ),

we obtain

),

we obtain

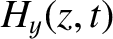

We saw earlier, in Section 6.7, that the  -directed propagation of a plane electromagnetic

wave, linearly polarized in the

-directed propagation of a plane electromagnetic

wave, linearly polarized in the  -direction, through a dielectric medium is

governed by (see Appendix C)

-direction, through a dielectric medium is

governed by (see Appendix C)

in the form (9.19),

in the form (9.19),  in the form

where

in the form

where  is the effective impedance of the plasma, and

is the effective impedance of the plasma, and  in the form (9.23),

Equations (9.24) and (9.25) yield the nonlinear dispersion relation (see Exercise 3)

where

in the form (9.23),

Equations (9.24) and (9.25) yield the nonlinear dispersion relation (see Exercise 3)

where

is the velocity of light in vacuum, and the

so-called (electron) plasma frequency,

is the characteristic frequency of

collective electron oscillations in the plasma (Stix 1962). Equations (9.24) and (9.25) also yield

where

is the velocity of light in vacuum, and the

so-called (electron) plasma frequency,

is the characteristic frequency of

collective electron oscillations in the plasma (Stix 1962). Equations (9.24) and (9.25) also yield

where

is the impedance of free space, and

the effective refractive index of the plasma. We, thus, conclude that sinusoidal electromagnetic

waves propagating through an unmagnetized plasma have a nonlinear dispersion relation.

Moreover, this nonlinearity arises because the effective refractive index of the plasma is frequency dependent.

is the impedance of free space, and

the effective refractive index of the plasma. We, thus, conclude that sinusoidal electromagnetic

waves propagating through an unmagnetized plasma have a nonlinear dispersion relation.

Moreover, this nonlinearity arises because the effective refractive index of the plasma is frequency dependent.

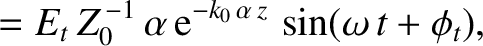

The expression (9.30) for the refractive index of a plasma has some rather

unusual properties. For wave frequencies lying above the plasma frequency (i.e.,

), it yields a real refractive index that is

less than unity. On the other hand, for wave frequencies lying below the plasma

frequency (i.e.,

), it yields a real refractive index that is

less than unity. On the other hand, for wave frequencies lying below the plasma

frequency (i.e.,

), it yields an imaginary refractive index. Neither of these results makes much sense. The former result is problematic because if the

refractive index is less than unity then the phase velocity of the wave,

), it yields an imaginary refractive index. Neither of these results makes much sense. The former result is problematic because if the

refractive index is less than unity then the phase velocity of the wave,

, becomes

superluminal (i.e.,

, becomes

superluminal (i.e.,  ), and superluminal velocities are generally thought to be unphysical.

The latter result is problematic because an imaginary refractive index implies an

imaginary phase velocity, which seems utterly meaningless. Let us investigate further.

), and superluminal velocities are generally thought to be unphysical.

The latter result is problematic because an imaginary refractive index implies an

imaginary phase velocity, which seems utterly meaningless. Let us investigate further.

Consider, first of all, the high-frequency limit,

. According to

Equation (9.30), a sinusoidal electromagnetic wave of angular frequency

. According to

Equation (9.30), a sinusoidal electromagnetic wave of angular frequency

propagates through the plasma

at the superluminal phase velocity

propagates through the plasma

at the superluminal phase velocity

. Differentiating the dispersion relation (9.27) with respect to

. Differentiating the dispersion relation (9.27) with respect to

, we obtain

, we obtain

|

(9.32) |

|

(9.33) |

). Hence, as

long as we accept that high-frequency electromagnetic waves transmit information through a plasma at

the group velocity, rather than the phase velocity, then there is no problem with causality.

Incidentally, it follows, from this discussion, that the phase velocity of dispersive

waves has very little physical significance. It is the group velocity that matters. For instance, according to Equations (6.128), (9.29), (9.30), and (9.34), the mean flux of electromagnetic energy in

the

). Hence, as

long as we accept that high-frequency electromagnetic waves transmit information through a plasma at

the group velocity, rather than the phase velocity, then there is no problem with causality.

Incidentally, it follows, from this discussion, that the phase velocity of dispersive

waves has very little physical significance. It is the group velocity that matters. For instance, according to Equations (6.128), (9.29), (9.30), and (9.34), the mean flux of electromagnetic energy in

the  -direction due to a high-frequency sinusoidal wave propagating through a plasma is given by

because

-direction due to a high-frequency sinusoidal wave propagating through a plasma is given by

because

and

and

.

Thus, if the group velocity is zero, as is the case when

.

Thus, if the group velocity is zero, as is the case when

, then there is zero energy flux associated with the wave.

, then there is zero energy flux associated with the wave.

The fact that the energy flux and the group velocity of a sinusoidal wave propagating through a plasma both go to zero when

suggests that the wave ceases to propagate at all in the low-frequency limit,

suggests that the wave ceases to propagate at all in the low-frequency limit,

. This observation leads us to search for

spatially decaying, standing wave solutions to Equations (9.24) and (9.25) of the form,

. This observation leads us to search for

spatially decaying, standing wave solutions to Equations (9.24) and (9.25) of the form,

, and also yields

as well as

(See Exercise 4.)

Furthermore, the mean

, and also yields

as well as

(See Exercise 4.)

Furthermore, the mean  -directed electromagnetic energy flux becomes

-directed electromagnetic energy flux becomes

|

(9.41) |

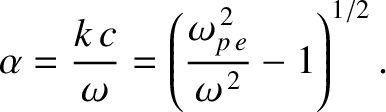

radians out of phase), and

the wave consequentially has zero associated net energy flux. This suggests that a

plasma reflects, rather than absorbs, an incident electromagnetic wave whose frequency is less than the plasma frequency (because if the wave were absorbed

then there would be a net flux of energy into the plasma). Let us investigate what happens

when a low-frequency electromagnetic wave is normally incident on a plasma in more detail.

radians out of phase), and

the wave consequentially has zero associated net energy flux. This suggests that a

plasma reflects, rather than absorbs, an incident electromagnetic wave whose frequency is less than the plasma frequency (because if the wave were absorbed

then there would be a net flux of energy into the plasma). Let us investigate what happens

when a low-frequency electromagnetic wave is normally incident on a plasma in more detail.

Suppose that the region  is a vacuum, and the region

is a vacuum, and the region  is

occupied by a plasma of plasma frequency

is

occupied by a plasma of plasma frequency

. Let the wave electric and

magnetic fields in the vacuum region take the form

. Let the wave electric and

magnetic fields in the vacuum region take the form

is the vacuum wavenumber.

Here,

is the vacuum wavenumber.

Here,  is the amplitude of an electromagnetic wave of frequency

is the amplitude of an electromagnetic wave of frequency

that is normally incident on the plasma, whereas

that is normally incident on the plasma, whereas  is the amplitude

of the reflected wave, and

is the amplitude

of the reflected wave, and  the phase of this wave with respect to the

incident wave.

The wave electric and magnetic fields in the plasma are written

the phase of this wave with respect to the

incident wave.

The wave electric and magnetic fields in the plasma are written

|

|

(9.44) |

|

|

(9.45) |

is the amplitude of the evanescent wave that penetrates into the

plasma,

is the amplitude of the evanescent wave that penetrates into the

plasma,  is the phase of this wave with respect to the incident wave, and

is the phase of this wave with respect to the incident wave, and

|

(9.46) |

and

and  at the vacuum/plasma interface (

at the vacuum/plasma interface ( ). (See Appendix C.)

In other words,

These two equations, which must be satisfied at all times, can be solved to give

(See Exercise 5.)

Thus, the coefficient of reflection,

). (See Appendix C.)

In other words,

These two equations, which must be satisfied at all times, can be solved to give

(See Exercise 5.)

Thus, the coefficient of reflection,

|

(9.53) |

) to

) to

(when

(when

) radians.

) radians.

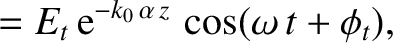

The outer regions of the Earth's atmosphere consist of a tenuous gas that is

partially ionized by ultraviolet and X-ray radiation from the Sun, as well as by cosmic rays incident from outer space. This

region, which is known as the ionosphere, acts like a plasma

as far as its interaction with radio waves is concerned. The ionosphere

consists of many layers. The two most important, as far as radio

wave propagation is concerned, are the E layer, which lies at an altitude of

about 90 to 120 km above the Earth's surface, and the F layer, which

lies at an altitude of about 120 to 400 km (Pain 1999). The plasma frequency in the

F layer is generally larger than that in the E layer, because of the greater

density of free electrons in the former (recall that

).

The free electron number density in the

E layer drops steeply after sunset, due to the lack of solar ionization combined with the gradual recombination of free electrons

and ions. Consequently, the plasma frequency in the E layer also drops steeply after sunset. Recombination in the F layer occurs at a much slower rate, so there is nothing like

as great a reduction in the plasma frequency of this layer at night.

Very High Frequency (VHF) radio signals (i.e., signals with frequencies greater than 30 MHz), which include FM radio and TV signals, have frequencies well in excess

of the plasma frequencies of both the E and the F layers, and thus pass straight through

the ionosphere. Short Wave (SW) radio signals (i.e., signals with frequencies in the

range 3 to 30 MHz) have frequencies in excess of the plasma

frequency of the E layer, but not of the F layer. Hence, SW signals pass through the

E layer, but are reflected by the F layer.

Finally, Medium Wave (MW) radio signals (i.e., signals with frequencies in the range

).

The free electron number density in the

E layer drops steeply after sunset, due to the lack of solar ionization combined with the gradual recombination of free electrons

and ions. Consequently, the plasma frequency in the E layer also drops steeply after sunset. Recombination in the F layer occurs at a much slower rate, so there is nothing like

as great a reduction in the plasma frequency of this layer at night.

Very High Frequency (VHF) radio signals (i.e., signals with frequencies greater than 30 MHz), which include FM radio and TV signals, have frequencies well in excess

of the plasma frequencies of both the E and the F layers, and thus pass straight through

the ionosphere. Short Wave (SW) radio signals (i.e., signals with frequencies in the

range 3 to 30 MHz) have frequencies in excess of the plasma

frequency of the E layer, but not of the F layer. Hence, SW signals pass through the

E layer, but are reflected by the F layer.

Finally, Medium Wave (MW) radio signals (i.e., signals with frequencies in the range

to 3 MHz) have frequencies that lie below the plasma frequency of the F layer,

and also lie below the plasma frequency of the E layer during daytime, but not

during nighttime. Thus, MW signals are reflected by the E layer during the day,

but pass through the E layer, and are reflected by the F layer, during the night.

to 3 MHz) have frequencies that lie below the plasma frequency of the F layer,

and also lie below the plasma frequency of the E layer during daytime, but not

during nighttime. Thus, MW signals are reflected by the E layer during the day,

but pass through the E layer, and are reflected by the F layer, during the night.

The reflection and transmission of the various different types of radio wave by the ionosphere is shown schematically in Figure 9.1. This diagram explains many of the characteristic features of radio reception. For instance, because of the curvature of the Earth's surface, VHF reception is only possible when the receiving antenna lies in the line of sight of the transmitting antenna, and is consequently fairly local in nature. MW reception is possible over much larger distances, because the signal is reflected by the ionosphere back toward the Earth's surface. Moreover, long range MW reception improves at night, because the signal is reflected at a higher altitude. Finally, SW radio reception is possible over very large distances, because the signal is reflected at extremely high altitudes.