Next: Mars

Up: Planetary Latitudes

Previous: Introduction

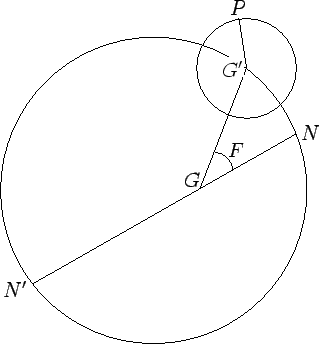

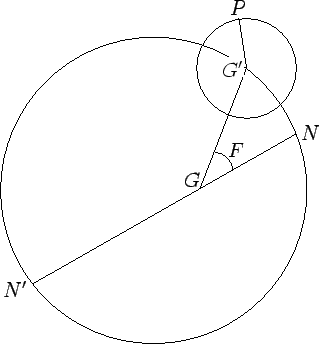

Figure 34 shows the orbit of a superior planet.

As we have already mentioned, the deferent and epicycle of such a planet have the same elements as

the orbit of the planet in question around the sun, and the apparent orbit of the

sun around the earth, respectively. It follows that the deferent and epicycle of a

superior planet are, respectively, inclined and parallel to the ecliptic plane.

(Recall that the ecliptic plane corresponds to the

plane of the sun's apparent orbit about the earth.) Let the plane of the deferent cut the

ecliptic plane along the line  . Here,

. Here,  is the point at which the

deferent passes through the plane of the ecliptic from south to north, in the direction of the

mean planetary motion. This point is called the ascending node.

Note that the line

is the point at which the

deferent passes through the plane of the ecliptic from south to north, in the direction of the

mean planetary motion. This point is called the ascending node.

Note that the line  must pass through point

must pass through point  , since the

earth is common to the plane of the deferent and the ecliptic plane.

Now, it follows from simple geometry that the elevation of the guide-point

, since the

earth is common to the plane of the deferent and the ecliptic plane.

Now, it follows from simple geometry that the elevation of the guide-point  above of the

ecliptic plane satisfies

above of the

ecliptic plane satisfies

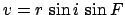

, where

, where  is the length

is the length  ,

,  the fixed inclination of the

planetary orbit (and, hence, of the deferent) to the ecliptic plane, and

the fixed inclination of the

planetary orbit (and, hence, of the deferent) to the ecliptic plane, and  the angle

the angle  . The

angle

. The

angle  is termed the argument of latitude. We can write (see Cha. 8)

is termed the argument of latitude. We can write (see Cha. 8)

|

(205) |

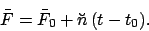

where  is the mean argument of latitude, and

is the mean argument of latitude, and  the equation of center of the deferent. Note that

the equation of center of the deferent. Note that  increases uniformly in time: i.e.,

increases uniformly in time: i.e.,

|

(206) |

Now, since the epicycle is parallel to the ecliptic

plane, the elevation of the planet above the said plane is

the same as that of the guide-point. Hence, from simple geometry, the ecliptic latitude of the planet satisfies

|

(207) |

where  is the length

is the length  , and

we have used the small angle approximation. However, it is apparent from Fig. 31 that

, and

we have used the small angle approximation. However, it is apparent from Fig. 31 that

|

(208) |

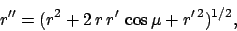

where  the length

the length  , and

, and  the

equation of the epicycle. But, according to the analysis in Cha. 8,

the

equation of the epicycle. But, according to the analysis in Cha. 8,  , where

, where  is the planetary

major radius in units in which the major radius of the sun's apparent orbit

about the earth is unity, and

is the planetary

major radius in units in which the major radius of the sun's apparent orbit

about the earth is unity, and  is defined in Eq. (158).

Thus, we obtain

is defined in Eq. (158).

Thus, we obtain

|

(209) |

where

|

(210) |

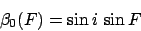

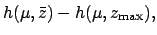

is termed the deferential latitude,

and

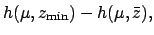

![\begin{displaymath}

h(\mu,z) = \left[1 + 2\,(a\,z)^{-1}\,\cos\mu+ (a\,z)^{-2}\right]^{-1/2}

\end{displaymath}](img2023.png) |

(211) |

the epicyclic latitude correction factor.

Figure 34:

Orbit of a superior planet. Here,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

,

,  , and

, and  represent the earth, guide-point,

planet, ascending node, descending node, and argument of latitude, respectively. View is from northern

ecliptic pole.

represent the earth, guide-point,

planet, ascending node, descending node, and argument of latitude, respectively. View is from northern

ecliptic pole.

|

In the following,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are elements of the orbit of the planet in question

about the sun, and

are elements of the orbit of the planet in question

about the sun, and  ,

,  , and

, and  are elements of the sun's apparent orbit

about the earth.

The requisite elements for all of the superior planets at the J2000 epoch (

are elements of the sun's apparent orbit

about the earth.

The requisite elements for all of the superior planets at the J2000 epoch (

JD)

are listed in Tables 30 and 66.

Employing a quadratic interpolation scheme to represent

JD)

are listed in Tables 30 and 66.

Employing a quadratic interpolation scheme to represent

(see Cha. 8), our procedure for determining the ecliptic latitude of a

superior planet is summed up by the following formuale:

(see Cha. 8), our procedure for determining the ecliptic latitude of a

superior planet is summed up by the following formuale:

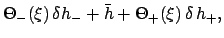

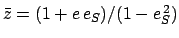

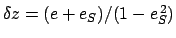

|

|

|

(212) |

|

|

|

(213) |

|

|

|

(214) |

|

|

|

(215) |

|

|

|

(216) |

|

|

|

(217) |

|

|

|

(218) |

|

|

|

(219) |

|

|

![$\displaystyle h(\mu,\bar{z})\equiv\left[1 + 2\,(a\,\bar{z})^{-1}\,\cos\mu+ (a\,\bar{z})^{-2}\right]^{-1/2},$](img2031.png) |

(220) |

|

|

|

(221) |

|

|

|

(222) |

|

|

|

(223) |

|

|

|

(224) |

|

|

|

(225) |

|

|

|

(226) |

Here,

,

,

,

,

,

and

,

and

. The constants

. The constants  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  for each of the superior planets are listed in Table 44. Finally, the functions

for each of the superior planets are listed in Table 44. Finally, the functions  are tabulated in Table 45.

are tabulated in Table 45.

For the case of Mars, the above formulae are capable of matching NASA ephemeris data during the years 1995-2006 CE

with a mean error of  and a maximum error of

and a maximum error of  . For the case of Jupiter, the mean error is

. For the case of Jupiter, the mean error is

and the maximum error

and the maximum error  . Finally, for the case of Saturn, the mean error is

. Finally, for the case of Saturn, the mean error is  and the

maximum error

and the

maximum error  .

.

Next: Mars

Up: Planetary Latitudes

Previous: Introduction

Richard Fitzpatrick

2010-07-21

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

,

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are elements of the orbit of the planet in question

about the sun, and

are elements of the orbit of the planet in question

about the sun, and ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are elements of the sun's apparent orbit

about the earth.

The requisite elements for all of the superior planets at the J2000 epoch (

are elements of the sun's apparent orbit

about the earth.

The requisite elements for all of the superior planets at the J2000 epoch (

![]() JD)

are listed in Tables 30 and 66.

Employing a quadratic interpolation scheme to represent

JD)

are listed in Tables 30 and 66.

Employing a quadratic interpolation scheme to represent

![]() (see Cha. 8), our procedure for determining the ecliptic latitude of a

superior planet is summed up by the following formuale:

(see Cha. 8), our procedure for determining the ecliptic latitude of a

superior planet is summed up by the following formuale:

![$\displaystyle h(\mu,\bar{z})\equiv\left[1 + 2\,(a\,\bar{z})^{-1}\,\cos\mu+ (a\,\bar{z})^{-2}\right]^{-1/2},$](img2031.png)

![]() and a maximum error of

and a maximum error of ![]() . For the case of Jupiter, the mean error is

. For the case of Jupiter, the mean error is

![]() and the maximum error

and the maximum error ![]() . Finally, for the case of Saturn, the mean error is

. Finally, for the case of Saturn, the mean error is ![]() and the

maximum error

and the

maximum error ![]() .

.