Next: Specific heats

Up: Applications of statistical thermodynamics

Previous: The equipartition theorem

Harmonic oscillators

Our proof of the equipartition theorem depends crucially on the classical approximation. To see how

quantum effects modify this result, let us examine a particularly simple system

which we know how to analyze using both classical and quantum physics: i.e.,

a

simple harmonic oscillator. Consider a one-dimensional harmonic oscillator in equilibrium

with a heat reservoir at temperature  . The energy of the oscillator is given by

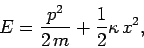

. The energy of the oscillator is given by

|

(467) |

where the first term on the right-hand side is the kinetic energy, involving the momentum

and mass

and mass  , and the second term is the potential energy, involving the displacement

, and the second term is the potential energy, involving the displacement

and the force constant

and the force constant  . Each of these terms is quadratic in the respective

variable. So, in the classical approximation the equipartition theorem yields:

. Each of these terms is quadratic in the respective

variable. So, in the classical approximation the equipartition theorem yields:

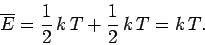

That is, the mean kinetic energy of the oscillator is equal

to the mean potential energy which

equals  . It follows that the mean total energy is

. It follows that the mean total energy is

|

(470) |

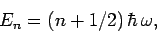

According to quantum mechanics, the energy levels of a harmonic oscillator are equally

spaced and satisfy

|

(471) |

where  is a non-negative integer, and

is a non-negative integer, and

|

(472) |

The partition function for such an oscillator is given by

![\begin{displaymath}

Z = \sum_{n=0}^\infty \exp(-\beta \,E_n) = \exp[-(1/2)\,\bet...

... \,\omega]

\sum_{n=0}^\infty \exp(- n\,\beta\, \hbar\,\omega).

\end{displaymath}](img1092.png) |

(473) |

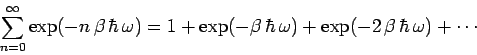

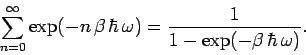

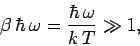

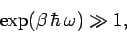

Now,

|

(474) |

is simply the sum of an infinite geometric series, and can be evaluated immediately,

|

(475) |

Thus, the partition function takes the form

![\begin{displaymath}

Z = \frac{ \exp[-(1/2)\,\beta\,\hbar\,\omega]}{1-\exp(-\beta\,\hbar\,\omega)},

\end{displaymath}](img1095.png) |

(476) |

and

![\begin{displaymath}

\ln Z = - \frac{1}{2}\,\beta\,\hbar\,\omega -\ln [1- \exp(-\beta\,\hbar\,\omega)]

\end{displaymath}](img1096.png) |

(477) |

The mean energy of the oscillator is given by [see Eq. (399)]

![\begin{displaymath}

\overline{E} = - \frac{\partial}{\partial \beta} \ln Z = -

\...

...omega)\,\hbar\,\omega}

{1-\exp(-\beta\,\hbar\,\omega)}\right],

\end{displaymath}](img1097.png) |

(478) |

or

![\begin{displaymath}

\overline{E} = \hbar \,\omega \left[ \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{\exp(\beta\, \hbar\,

\omega)-1}

\right].

\end{displaymath}](img1098.png) |

(479) |

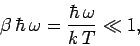

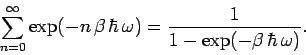

Consider the limit

|

(480) |

in which the thermal energy  is large compared to the separation

is large compared to the separation

between the

energy levels. In this limit,

between the

energy levels. In this limit,

|

(481) |

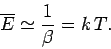

so

![\begin{displaymath}

\overline{E} \simeq \hbar\,\omega\left[\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1...

...meq \hbar\,\omega\left[ \frac{1}{\beta\,\hbar\,\omega}\right],

\end{displaymath}](img1102.png) |

(482) |

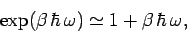

giving

|

(483) |

Thus, the classical result (470) holds whenever the thermal energy greatly exceeds the typical

spacing between quantum energy levels.

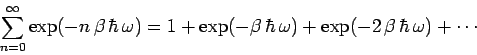

Consider the limit

|

(484) |

in which the thermal energy is small compared to the separation between

the energy levels. In this limit,

|

(485) |

and so

![\begin{displaymath}

\overline{E} \simeq \hbar\,\omega \,[ 1/2 + \exp(-\beta\,\hbar\,\omega)] \simeq

\frac{1}{2} \,\hbar \,\omega.

\end{displaymath}](img1106.png) |

(486) |

Thus, if the thermal energy is much less than the spacing between quantum states then

the mean energy approaches that of the ground-state (the so-called zero point

energy).

Clearly, the equipartition theorem is only valid in the former limit, where

, and the oscillator possess sufficient thermal energy to explore many

of its possible quantum states.

, and the oscillator possess sufficient thermal energy to explore many

of its possible quantum states.

Next: Specific heats

Up: Applications of statistical thermodynamics

Previous: The equipartition theorem

Richard Fitzpatrick

2006-02-02

![\begin{displaymath}

Z = \sum_{n=0}^\infty \exp(-\beta \,E_n) = \exp[-(1/2)\,\bet...

... \,\omega]

\sum_{n=0}^\infty \exp(- n\,\beta\, \hbar\,\omega).

\end{displaymath}](img1092.png)

![\begin{displaymath}

Z = \frac{ \exp[-(1/2)\,\beta\,\hbar\,\omega]}{1-\exp(-\beta\,\hbar\,\omega)},

\end{displaymath}](img1095.png)

![\begin{displaymath}

\overline{E} = - \frac{\partial}{\partial \beta} \ln Z = -

\...

...omega)\,\hbar\,\omega}

{1-\exp(-\beta\,\hbar\,\omega)}\right],

\end{displaymath}](img1097.png)

![\begin{displaymath}

\overline{E} \simeq \hbar\,\omega\left[\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1...

...meq \hbar\,\omega\left[ \frac{1}{\beta\,\hbar\,\omega}\right],

\end{displaymath}](img1102.png)