Next: Specific Heats of Gases

Up: Applications of Statistical Thermodynamics

Previous: Harmonic Oscillators

We have discussed the internal energies and entropies of

substances (mostly ideal gases)

at some length. Unfortunately, these quantities cannot be directly

measured.

Instead, they must

be inferred from other information. The thermodynamic property of substances that

is the easiest to measure is, of course, the heat capacity, or specific heat. In fact,

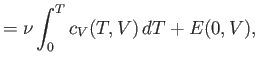

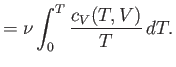

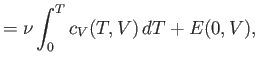

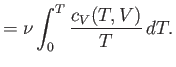

once the variation of the specific heat with temperature is known, both the internal

energy and entropy can be easily reconstructed via

Here, use has been made of

, and the third law of thermodynamics.

Clearly, the optimum way of verifying the results of statistical thermodynamics

is to compare the

theoretically predicted heat capacities with the experimentally measured values.

, and the third law of thermodynamics.

Clearly, the optimum way of verifying the results of statistical thermodynamics

is to compare the

theoretically predicted heat capacities with the experimentally measured values.

Classical physics, in the guise of the equipartition theorem, says that each

independent degree of freedom associated with a quadratic term in the energy

possesses an average energy

in thermal equilibrium at temperature

in thermal equilibrium at temperature

. Consider a substance made up of

. Consider a substance made up of  molecules. Every molecular

degree of freedom contributes

molecules. Every molecular

degree of freedom contributes

,

or

,

or

, to the mean energy of the substance (with the tacit proviso

that each degree of freedom is associated with a quadratic term in the energy).

Thus, the contribution to the molar heat capacity at constant volume (we wish to

avoid the complications associated with any external work done on the substance) is

, to the mean energy of the substance (with the tacit proviso

that each degree of freedom is associated with a quadratic term in the energy).

Thus, the contribution to the molar heat capacity at constant volume (we wish to

avoid the complications associated with any external work done on the substance) is

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{\nu}\left( \frac{\partial \overline{E}}{\partial T}\righ...

...rac{1}{\nu} \frac{\partial[ (1/2) \nu R T] }{\partial T}= \frac{1}{2} R,$](img1542.png) |

(7.158) |

per molecular degree of freedom. The total classical heat capacity is

therefore

|

(7.159) |

where  is the number of molecular degrees of freedom. Because large complicated

molecules clearly have very many more degrees of freedom than small simple

molecules, the previous formula predicts that the molar

heat capacities of substances

made up of the former type of molecules

should greatly exceed those of substances made

up of the latter. In fact, the experimental heat capacities of substances containing

complicated molecules are generally greater than those of

substances containing simple molecules,

but by nowhere near the large factor predicted in Equation (7.159). This equation also

implies that heat capacities are temperature independent. In fact,

this is not the case for most substances.

Experimental heat capacities generally increase with

increasing temperature. These two experimental

facts pose severe problems for classical physics.

Incidentally, these problems

were fully appreciated as far back as 1850. Stories that physicists at the end

of the nineteenth

century

thought that classical physics explained absolutely everything are largely apocryphal.

is the number of molecular degrees of freedom. Because large complicated

molecules clearly have very many more degrees of freedom than small simple

molecules, the previous formula predicts that the molar

heat capacities of substances

made up of the former type of molecules

should greatly exceed those of substances made

up of the latter. In fact, the experimental heat capacities of substances containing

complicated molecules are generally greater than those of

substances containing simple molecules,

but by nowhere near the large factor predicted in Equation (7.159). This equation also

implies that heat capacities are temperature independent. In fact,

this is not the case for most substances.

Experimental heat capacities generally increase with

increasing temperature. These two experimental

facts pose severe problems for classical physics.

Incidentally, these problems

were fully appreciated as far back as 1850. Stories that physicists at the end

of the nineteenth

century

thought that classical physics explained absolutely everything are largely apocryphal.

The equipartition theorem (and the whole classical approximation) is only valid

when the typical thermal energy,  , greatly exceeds the spacing between quantum

energy levels. Suppose that the temperature is sufficiently low that this

condition is not satisfied for one particular molecular degree of freedom.

In fact, suppose that

, greatly exceeds the spacing between quantum

energy levels. Suppose that the temperature is sufficiently low that this

condition is not satisfied for one particular molecular degree of freedom.

In fact, suppose that  is much less than the spacing between

the energy levels.

According to Section 7.11, in this situation, the degree of freedom only contributes

the ground-state energy,

is much less than the spacing between

the energy levels.

According to Section 7.11, in this situation, the degree of freedom only contributes

the ground-state energy,  (say) to the mean energy of the molecule. Now, the

ground-state energy can be a quite complicated

function of the internal properties of the

molecule, but is certainly not a function of the temperature, because this is

a collective property of all molecules. It follows that the contribution to

the molar heat capacity is

(say) to the mean energy of the molecule. Now, the

ground-state energy can be a quite complicated

function of the internal properties of the

molecule, but is certainly not a function of the temperature, because this is

a collective property of all molecules. It follows that the contribution to

the molar heat capacity is

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{\nu}\left( \frac{\partial [N E_0]}{\partial T}\right)_V = 0.$](img1544.png) |

(7.160) |

Thus, if  is much less than the spacing between the energy levels then

the degree of

freedom contributes nothing at all

to the molar heat capacity. We say that this particular

degree of freedom is ``frozen out.'' Clearly, at very low temperatures, just about

all degrees of freedom are frozen out. As the temperature is gradually increased,

degrees of freedom successively

kick in, and eventually contribute their full

is much less than the spacing between the energy levels then

the degree of

freedom contributes nothing at all

to the molar heat capacity. We say that this particular

degree of freedom is ``frozen out.'' Clearly, at very low temperatures, just about

all degrees of freedom are frozen out. As the temperature is gradually increased,

degrees of freedom successively

kick in, and eventually contribute their full  to

the molar heat capacity, as

to

the molar heat capacity, as  approaches, and then greatly exceeds, the spacing

between their

quantum energy levels. We can use these simple ideas to explain the behaviors

of most

experimental heat capacities.

approaches, and then greatly exceeds, the spacing

between their

quantum energy levels. We can use these simple ideas to explain the behaviors

of most

experimental heat capacities.

To make further progress, we need to

estimate the typical spacing between the quantum energy levels

associated with various degrees of freedom.

We can do this by observing the

frequency

of the electromagnetic radiation emitted and absorbed during transitions between

these energy levels. If the typical spacing between energy levels is

then

transitions between the various levels are associated with photons of

frequency

then

transitions between the various levels are associated with photons of

frequency  , where

, where

. (Here,

. (Here,  is Planck's constant.) We can define an effective

temperature of the radiation via

is Planck's constant.) We can define an effective

temperature of the radiation via

. If

. If

then

then

, and the degree of freedom makes its

full contribution to the heat capacity. On the other hand, if

, and the degree of freedom makes its

full contribution to the heat capacity. On the other hand, if

then

then

, and the degree of freedom is frozen out.

Table 7.1 lists the ``temperatures'' of various different types of radiation.

It is clear that degrees of freedom that give rise to emission or absorption

of radio or microwave radiation contribute their full

, and the degree of freedom is frozen out.

Table 7.1 lists the ``temperatures'' of various different types of radiation.

It is clear that degrees of freedom that give rise to emission or absorption

of radio or microwave radiation contribute their full  to the molar heat capacity at room temperature. On the other hand, degrees of freedom that give rise to

emission or absorption in the visible, ultraviolet, X-ray, or

to the molar heat capacity at room temperature. On the other hand, degrees of freedom that give rise to

emission or absorption in the visible, ultraviolet, X-ray, or  -ray

regions of the electromagnetic spectrum are frozen out at room temperature.

Degrees of freedom that emit or absorb infrared radiation are on the border line.

-ray

regions of the electromagnetic spectrum are frozen out at room temperature.

Degrees of freedom that emit or absorb infrared radiation are on the border line.

Table 7.1:

Effective ``temperatures'' of various types of electromagnetic radiation.

| Radiation type |

Frequency (hz) |

(K)

(K) |

| Radio |

|

|

| Microwave |

-

-

|

-

-

|

| Infrared |

-

-

|

-

-

|

| Visible |

|

|

| Ultraviolet |

-

-

|

-

-

|

| X-ray |

-

-

|

-

-

|

-ray

-ray |

|

|

|

Next: Specific Heats of Gases

Up: Applications of Statistical Thermodynamics

Previous: Harmonic Oscillators

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-25

![]() in thermal equilibrium at temperature

in thermal equilibrium at temperature

![]() . Consider a substance made up of

. Consider a substance made up of ![]() molecules. Every molecular

degree of freedom contributes

molecules. Every molecular

degree of freedom contributes

![]() ,

or

,

or

![]() , to the mean energy of the substance (with the tacit proviso

that each degree of freedom is associated with a quadratic term in the energy).

Thus, the contribution to the molar heat capacity at constant volume (we wish to

avoid the complications associated with any external work done on the substance) is

, to the mean energy of the substance (with the tacit proviso

that each degree of freedom is associated with a quadratic term in the energy).

Thus, the contribution to the molar heat capacity at constant volume (we wish to

avoid the complications associated with any external work done on the substance) is

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{\nu}\left( \frac{\partial \overline{E}}{\partial T}\righ...

...rac{1}{\nu} \frac{\partial[ (1/2) \nu R T] }{\partial T}= \frac{1}{2} R,$](img1542.png)

![]() , greatly exceeds the spacing between quantum

energy levels. Suppose that the temperature is sufficiently low that this

condition is not satisfied for one particular molecular degree of freedom.

In fact, suppose that

, greatly exceeds the spacing between quantum

energy levels. Suppose that the temperature is sufficiently low that this

condition is not satisfied for one particular molecular degree of freedom.

In fact, suppose that ![]() is much less than the spacing between

the energy levels.

According to Section 7.11, in this situation, the degree of freedom only contributes

the ground-state energy,

is much less than the spacing between

the energy levels.

According to Section 7.11, in this situation, the degree of freedom only contributes

the ground-state energy, ![]() (say) to the mean energy of the molecule. Now, the

ground-state energy can be a quite complicated

function of the internal properties of the

molecule, but is certainly not a function of the temperature, because this is

a collective property of all molecules. It follows that the contribution to

the molar heat capacity is

(say) to the mean energy of the molecule. Now, the

ground-state energy can be a quite complicated

function of the internal properties of the

molecule, but is certainly not a function of the temperature, because this is

a collective property of all molecules. It follows that the contribution to

the molar heat capacity is

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{\nu}\left( \frac{\partial [N E_0]}{\partial T}\right)_V = 0.$](img1544.png)

![]() then

transitions between the various levels are associated with photons of

frequency

then

transitions between the various levels are associated with photons of

frequency ![]() , where

, where

![]() . (Here,

. (Here, ![]() is Planck's constant.) We can define an effective

temperature of the radiation via

is Planck's constant.) We can define an effective

temperature of the radiation via

![]() . If

. If

![]() then

then

![]() , and the degree of freedom makes its

full contribution to the heat capacity. On the other hand, if

, and the degree of freedom makes its

full contribution to the heat capacity. On the other hand, if

![]() then

then

![]() , and the degree of freedom is frozen out.

Table 7.1 lists the ``temperatures'' of various different types of radiation.

It is clear that degrees of freedom that give rise to emission or absorption

of radio or microwave radiation contribute their full

, and the degree of freedom is frozen out.

Table 7.1 lists the ``temperatures'' of various different types of radiation.

It is clear that degrees of freedom that give rise to emission or absorption

of radio or microwave radiation contribute their full ![]() to the molar heat capacity at room temperature. On the other hand, degrees of freedom that give rise to

emission or absorption in the visible, ultraviolet, X-ray, or

to the molar heat capacity at room temperature. On the other hand, degrees of freedom that give rise to

emission or absorption in the visible, ultraviolet, X-ray, or ![]() -ray

regions of the electromagnetic spectrum are frozen out at room temperature.

Degrees of freedom that emit or absorb infrared radiation are on the border line.

-ray

regions of the electromagnetic spectrum are frozen out at room temperature.

Degrees of freedom that emit or absorb infrared radiation are on the border line.